Long ago, I worked on a probate case that read like the start of a Netflix docuseries: a Florida carnival worker passed away with no known family, no will, and a modest mobile home, plus, surprise(!), a multimillion-dollar estate.

Stories like this aren’t as rare as you’d think. Whether your ancestors were millionaires or millwrights, probate records can reveal a lot more than who got grandma’s antique gravy boat. They’re often the only documents that name whole families, identify married daughters, or explain why Great-Aunt Pearl was mysteriously left out of the will (spoiler: family drama, always).

In this post, we’re diving into probate records, the what, the where, the why, and how these dusty old files can become your new favorite genealogy tool. Plus, I’ll show you where to find them (for free or cheap), what to do with them once you’ve got them, and what to watch out for so you don’t chase the wrong “John Smith” across three states.

This guide includes two helpful downloads – a Probate Records for Genealogy Cheat Sheet and a helpful checklist to guide your research. You can view these downloadable helpers on your device or print them off. Download them below.

Why Probate Records are an Often Underused Resource You Need for Your Family History Research

If the word “probate” makes you want to nap immediately, stick with me. Probate records aren’t legal snoozefests; they’re treasure maps for your family tree. Seriously.

What is Probate?

Probate is the legal process that starts after someone dies. If they left a will (testate), the court ensures that everything is distributed according to their wishes. If they didn’t leave a will (intestate) the process becomes more complex.

Depending on the jurisdiction, the estate can eventually pass to the state (also known as escheat) if no legitimate heirs are identified and proven in court. That means that if nobody steps forward or if the paperwork doesn’t support their claim, the government could inherit the entire estate. Ouch.

What Are Probate Records?

Probate records often include:

- Wills – where someone spells out “I leave my beloved niece Sally my tea set and absolutely nothing to my brother Frank.”

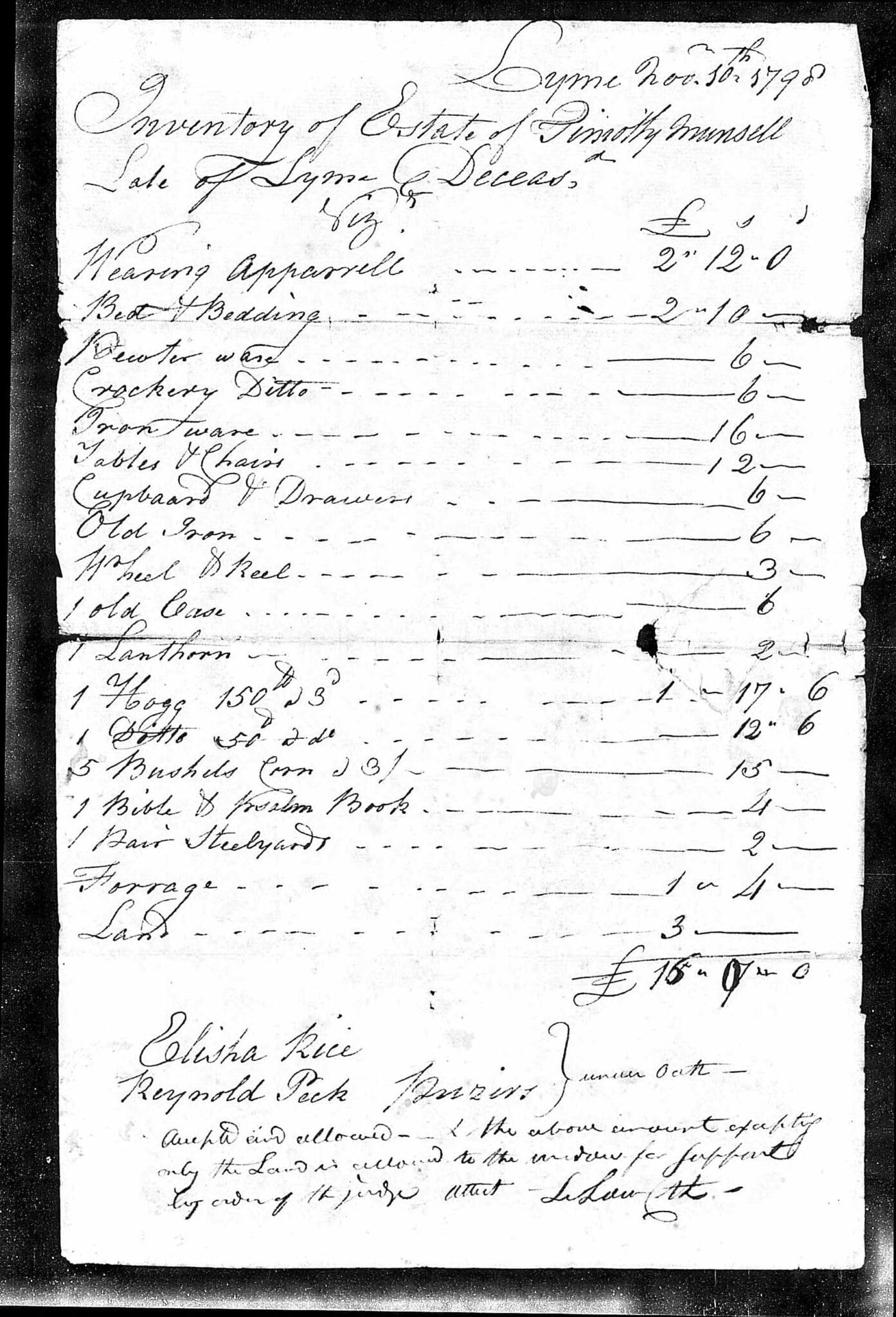

- Inventories – itemized lists of stuff they owned: land, tools, livestock, the aforementioned tea set.

- Petitions and affidavits – where family members argue over what should happen.

- Guardianship files – if minor children were involved.

- Letters of administration or testamentary – official court documents naming who’s in charge of wrapping things up.

You’ll also find names of spouses, kids, in-laws, neighbors, the family lawyer, and the random cousin who appeared out of nowhere when money got involved. Even if your ancestor didn’t have a big estate, there’s a good chance they left behind some sort of probate trail, especially if they owned property or owed anyone money.

Here is a fascinating inventory from a probate file in Connecticut:

Why should you use probate records for family history research?

Because probate records can:

- Prove relationships when birth certificates don’t exist

- Reveal unknown children, spouses, or name changes

- Show exactly where your ancestors lived and what they owned

- Offer personality clues (“I bequeath my prized shotgun to my best friend Earl” = storytelling gold)

So the next time you hit a dead end in your tree, don’t give up, go probate.

Genealogical Gold: What You’ll Find Inside Probate Records

You’d be surprised what you can discover in these fascinating records.

Names and Relationships

Probate records often spell out who’s who: sons, daughters, spouses, in-laws, and the occasionally mysterious “beloved companion” (you know the type). These can help confirm relationships or reveal relatives you didn’t know existed. For example, a will might name all of someone’s children, even those who never appeared in census records or were born from a previous marriage.

Maiden Names and Married Daughters

This one’s a big deal. Women can be elusive in the genealogical record, especially once they marry. Probate documents might reveal a daughter’s married name or list a widow as “the relict of John Smith,” which is your 19th-century clue that she was married to a now-deceased John Smith.

Locations and Land Ownership

Probate records can pinpoint where your ancestor lived, including town, township, and sometimes property lines. They can also show how property was passed down or divided. This is applicable if you’re tracking land records or family migration.

Personal Property Inventories

Here’s where the magic happens. A complete list of, “one bedstead, two feather beds, one butter churn, three hogs, and a cracked Bible” documents their belongings. It gives you a glimpse into how your ancestors lived. Were they wealthy? Did they read? Did they own a loom or a spinning wheel? These facts are the texture of their lives.

Signatures and Witnesses

Your ancestor’s signature (or “X, his mark”) might be there in ink, and so might the names of neighbors or family members who witnessed the will or inventory. These witnesses often lead to collateral lines or FAN Club research (Friends/Family, Associates, and Neighbors).

Guardianship and Orphans’ Court Files

If a parent died with minor children, you might find guardianship papers appointing a relative, or sometimes a non-relative, as their guardian. This can help explain who raised a child and why they show up in someone else’s household later on.

Excluded Heirs and Family Drama

Sometimes the most significant clues come from who’s not named. A will that says “I leave nothing to my son, George, for reasons he knows well” is both savage and helpful for establishing relationships.

In short? Probate records give you relationships, residences, real-life belongings, and sometimes a little bit of revenge. What more could a genealogist want?

Where to Find Probate Records: The Big Players and Hidden Gems

So, where are all these probate records hiding? Some are a click away. Others… might be buried in a courthouse basement guarded by a very skeptical clerk named Janet. Let’s start with the easy wins.

Major Online Platforms That Hold Probate Records for Genealogical Research

If you take advantage of some of the paid resources linked to on this page we may receive a small commission to help support the free content so many enjoy on our site. We only recommend and link to websites we love and use ourselves when we know they will be of use to you.

Free and full of surprises, FamilySearch has digitized (and microfilmed) probate records from around the world. Start by heading to their Catalog, type in the county and state where your ancestor lived, and look for categories like Probate Records, Wills, or Guardianships. Pro tip: skip the search bar and head straight for the catalog for more targeted results.

Find help for how to use the FamilySearch Catalog here.

Also, check out their Research Wiki, where volunteers in each locality have created a guide to where to find surviving records.

This subscription site boasts an impressive (and growing) collection of indexed wills and probate records, particularly for U.S. states such as Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Massachusetts. Searchable by name, state, and sometimes county, but be aware that not every county is covered, and some record sets are incomplete.

Tip: If you don’t know the county, start with the state-level collections and use filters to narrow down your search.

While not known primarily for probate, MyHeritage includes a range of court and probate records from the U.S., the U.K., and other countries. Their filters make it easy to sort by record type, and international researchers may find unique collections that are not available on different platforms.

Charming, a bit old-school, but often surprisingly helpful. Volunteers have uploaded transcripts, abstracts, and indexes of probate records by state and county. Some counties are more active than others, but it’s always worth a look.

Local and State Repositories That Contain These Records

County Courthouses

If your ancestor owned land or died in a specific county, their probate records probably started there. Call the clerk of court or probate division to ask what’s available and how to access it. Some will let you order copies by mail, while others may require an in-person visit or have off-site storage.

Tip: Ask if there are docket books or index volumes; these are goldmines for finding the correct file number before requesting the whole packet.

State Archives

Older probate records (typically pre-1900) are sometimes transferred from courthouses to state archives. Many states have searchable online catalogs, and a few even have digitized images. Don’t forget to check sites like WorldCat, Google Books, and Internet Archive for printed probate abstracts created by local genealogical societies.

Historical Societies

Local historical societies are the unsung heroes of probate research. Many have transcriptions, indexes, or even original documents donated by families. Even if they don’t have the record itself, the staff often know precisely where the courthouse records were stored, or lost, in 1897. Some societies will do lookups for a small fee (or a slice of gratitude).

Published Collections & Books Where You May Find Them

Before diving into the courthouse microfilm rabbit hole, see if someone has already abstracted the records. Many counties have published probate indexes or volumes of will abstracts created by researchers and genealogical societies.

Try searching:

- WorldCat.org

- Google Books – Search for state and county probate abstracts

- Internet Archive – Search ‘Probate Index [County/State]’

Tip: Abstracts are convenient, but they’re not a substitute for the original record. They may leave out juicy or critical details, like the deceased leaving a child one dollar while giving the other children more.

Not Everything Is Online (And That’s Okay)

Let’s be honest: we love a good digitized record. There’s nothing like finding a 200-year-old will while still in your pajamas, coffee in hand, cat judging you from across the room. But not everything has made it online, and that’s not a bad thing.

In fact, some of the best probate records are still stored in courthouse basements, state archive vaults, or filing cabinets in local historical societies that don’t even have websites. If you hit a brick wall online, the records might be only available offline like so many others.

Tips for Finding Offline Probate Records:

- Call the County Clerk: Yes, with an actual phone. Ask for the probate or surrogate’s court and the years it covers. Some clerks will even search indexes for you.

- Request the Docket Numbers First: Before ordering the whole file, ask if they can provide you with the docket number or index entry. It’ll save time (and copying fees).

- Check the State Archives, especially for older estates (pre-1900), as records may have been transferred from the county to the state. Many archives will do lookups or offer research guides.

- Use Published Guides: Books, county histories, and society-published indexes are often the only breadcrumb trails for locating off-the-grid records. Use WorldCat, Internet Archive, or even eBay to track them down.

- Ask Historical Societies: They may have probate abstracts, estate inventories, or even complete transcription projects that have been donated by local volunteers.

It might take a little more effort than a quick search box, but the payoff is worth it. Huge. You could be the first person in your family to see those documents in decades.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them When Using Probate Records in Your Research

Even the most experienced researchers have fallen into the probate pit at one time or another. The records can be tricky. Between confusing language, missing pages, and a suspicious number of people named “John,” it’s easy to make a wrong turn. Here are the most common mistakes, and how you can sidestep them like a genealogy ninja:

1. Relying Only on Indexes

Indexes are helpful, sure, but they’re like reading the back of a novel and thinking you know the whole story. Indexes might list names, dates, and file numbers, but they often leave out the juicy bits: relationships, property, feuds, and who got what and why. Always try to access the entire probate packet.

2. Misinterpreting Old Legal Terms

“Bequeath,” “legatee,” “issue,” “relict,” “executor,” “chattel”, these aren’t characters from a fantasy novel; they’re real probate lingo. If you don’t understand a word, look it up. For example:

- Relict = widow (not a dinosaur bone)

- Issue = descendants, not problems (usually)

- Escheat = property going to the state because no heirs could be proven

Tip: Keep a probate glossary handy. (Or better yet, make one in your research notes.) Here are some terms to get your started.

Glossary of Probate Terms

- Testate: Died with a valid will.

- Intestate: Died without a will.

- Executor: A person named in the will who will manage the estate.

- Administrator: Court-appointed estate manager when no will exists.

- Relict: Widow or widower of the deceased.

- Issue: Direct descendants (children, grandchildren, etc.).

- Escheat: Process where assets revert to the state due to no heirs.

- Legatee: Person who receives a bequest or gift via will.

- Chattel: Movable personal property (furniture, livestock, etc.).

- Dower: Portion of a deceased husband’s estate given to his widow.

3. Assuming Everyone Named in the File Was Family

Not necessarily. Witnesses, neighbors, business partners, and even adversaries appear in probate files. One “executor” may be a loyal son; another may be a lawyer.

4. Overlooking Women and Married Daughters

Women are often named in ways that make it challenging to trace them. This is especially true if they’ve married. Phrases like “my daughter, Mary, wife of Thomas Green” are helpful, but sometimes you only get “Mary Green” and have to figure out how she connects. Use probate to track those name changes and verify identities across documents.

5. Ignoring Jurisdiction Shifts

Counties split, boundaries changed, and some records got moved in the shuffle. If you can’t find a record where you think it should be, check the neighboring county or state archive. A family that lived in “Old Jefferson County” might suddenly show up in “New Washington County” after a redistricting.

6. Stopping at the First Will You Find

Sometimes there’s more than one file: a will and a guardianship, or multiple estate settlements years apart. Keep digging, you may find additional documents filed months or even years after the initial probate.

Avoiding these pitfalls will save you time and effort. It’ll also help you build a solid family history.

7. Not Creating a Timeline

A timeline can help you make sure you’re staying organized and not missing critical information. Don’t miss it.

How to Build a Probate Research Timeline to Organize Your Research

- Start with the ancestor’s date and place of death.

- Identify whether probate was filed, look for dockets or indexes.

- List every related record: will, inventory, guardian file, etc.

- Place each record on a timeline with date, type, and repository.

- Add collateral names (witnesses, heirs, executors).

- Overlay this timeline with census and land records for context.

- Highlight gaps in time or location; those are clues for more digging.

- Use this timeline to verify family relationships and estate flow.

When to Ask for Help

You’ve done the digging. You’ve scoured indexes and flipped through inventories. Maybe you have deciphered 18th-century chicken-scratch handwriting. But sometimes, probate research throws curveballs you can’t catch on your own.

That’s when it is time to call in reinforcements, also known as a professional genealogist (hi, nice to meet you).

When You Might Need Help:

- Out-of-Area Records: The records you need are locked in a courthouse three states away with no digital access, and no one returns your voicemails.

- Foreign-Language Documents: Your immigrant ancestor’s will is beautifully handwritten… in German script. From 1850. By someone who clearly didn’t believe in punctuation.

- Multiple Generations in the Same Area with the Same Name: If you’ve ever tried to figure out which James Johnson is your 3x-great-grandfather out of six living in the same county in 1870, you get it.

- Court Cases or Contested Estates: If the probate file turns into a courtroom drama, you may need help understanding legal outcomes, who won what, and how it affects your family line.

- Time-Sensitive Legal Needs: Sometimes, you’re researching for more than curiosity, such as proving descent for dual citizenship, DAR/SAR applications, or a legal inheritance. You don’t want to miss a deadline while stuck on page 2 of an 80-page packet.

Professional genealogists (like yours truly) can:

- Access records in faraway archives

- Translate old legal jargon

- Spot inconsistencies you might miss

- Create court-ready documentation if needed

If you’ve hit a wall, don’t stress. Even expert researchers call in help when the trail goes cold, or when courthouse Kevin won’t play nice.

Final Thoughts: Go Open a Will

If you’ve made it this far, congratulations, you’re off to a good start. Whether your ancestor was a frontier farmer, a city banker, or a carnie in a Florida trailer park with a suspiciously large bank account, there’s a decent chance they left behind a paper trail. That trail could lead you to family you didn’t know existed, stories you never expected, and answers to questions that have lasted for generations.

You don’t have to be a lawyer or a historian to crack open a probate file and find gold; you only need curiosity, patience, and a good strategy (and okay, maybe a magnifying glass or two).

So take a stab at it. Search FamilySearch. Check the courthouse. Email that historical society with the Yahoo address and the blurry website. Probate records might not always be glamorous, but they are powerful. Because sometimes, the most significant discoveries in genealogy don’t come from birth or death certificates. They come from what happens in between—after someone’s gone, and their story is still waiting to be found.

We hope this information makes your search for probate records a simple one. Good luck!

Really helpful! Great ideas I knew nothing about. Thank you for sharing.

Thank you, great rocks to look under.