As you dive deeper into your family history you will likely run across terminology that you have not seen before or that you may not fully understand. Even those of us who have made history a profession will sometimes run across terms that are no longer used or that have a specific application that’s unfamiliar.

Recently, on a trip to research my family’s history in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, I made sure to stop by the Bucks County Historical Archives at the Mercer Museum in Doylestown, PA. While waiting for the very kind and knowledgeable collections manager to retrieve a rare document from the closed stacks, I read an account of a man in the 1770’s who “absquatulated” with some cattle.

Now, before you get ahead of yourselves, there is nothing weird going on here – he simply took off with another man’s cows. In other words, he was a thief. Surprisingly, I had never seen the word absquatulated before. As I read on in the archives I found that there was a serious amount of absquatulating going on in Northampton County, Pennsylvania in colonial times!

Whether it’s a fantastic word like absquatulate, or something simpler, you are bound to run across words and terms you don’t know as you travel back in time. In this article, I will be talking about military terms from the Civil and Revolutionary War periods that you may not be familiar with.

The terms today’s soldiers and veterans take for granted, a soldier from the 1800’s would think was language from another planet – and vice versa – so, pay attention. You’ll likely find that you need this knowledge in your family history research.

If You’re Researching Civil War or Revolutionary War Records, Here Are Some Terms to Know

Brevet: Originally a promotion in name only, given as an honor for battlefield heroics or other service. The officer would not be given a corresponding raise in pay, nor the duties or authority of the brevet rank. For example, you might find yourself reading an entry that identifies someone as a major, but later he is referred to as “Brevet Lieutenant Colonel”, or “Bvt. Lt. Col.”

Commutation/Substitute: This term will generally not be found in genealogical records, but it may show up in your research of ancestors from the Civil War period.

In both the North and South, wealthier or connected men could buy their way out of the draft/military service by hiring a substitute. The draft was instituted in the North in 1863, and the ability of wealthy men to avoid service for themselves or their male relatives caused widespread anger. In New York, the deadliest riots in American history took place mainly as a reaction to this disparity between rich and poor.

Compiled Military Service Records/CMSR’s: These are collections of records marking an individual’s service. In certain collections, you may find a person’s name and “CMSR” with it. This means there is likely a binder or folder (sometimes made at the time) carrying all of the important papers from a person’s military service.

Contraband: An escaped enslaved person who fled to Union lines. On many occasions, escaped male slaves joined the Union Army.

CSA: Confederate States of America

Dragoon: British/European heavy or medium cavalryman. As opposed to the hussars below, dragoons carried rifles/muskets, and generally fought on foot, using horseback for rapid travel/deployment. One might see the abbreviation “drag.” indicating service in the dragoons.

Flying Camp: You might, if you’re looking for information on your colonial ancestor from Delaware, Maryland, or Pennsylvania, see this term.

Most people are familiar with the “Minutemen,” the militia said to be ready in a minute (not quite, but it sounds better than ‘half-hour men”). The “Flying Camp” was an organization of several thousand men from the states mentioned above, and were to be the Continental Army’s “Minutemen,” men ready for battle or reconnaissance at a moment’s notice. The Flying Camp unit operated for only a short time in the New York campaign of 1776. Their heavy losses caused the unit to be disbanded.

Furlough: Leave granted to a soldier/officer. Furlough papers had to be carried on your person at all times. They denoted what unit you were in, where you were headed, and when you were due to return.

The nature of military justice on both sides of the Civil War was quick and sometimes brutal. All states and many localities had units of soldiers/peace officers looking for deserters. If you were caught without your papers, you might be put on trial and hanged for desertion. On muster sheets, you will sometimes see a man’s name and “furl.” next to it, meaning they are on leave and still in the unit.

Grenadiers: As opposed to light infantry, grenadier units generally carried much equipment – most of it was, you guessed it, grenades. Of course, the grenades of the 18th century were more like the bombs one sees in cartoons today, round with a fuse – they also weighed a lot.

Grenadiers were usually bigger, stronger men who could carry much weight. The British, Hessians, and French used grenadiers during the Revolution. The American colonists, for the most part, eschewed the grenadier idea. In British military records, one sees the abbreviation “gren.” on occasion.

Hussars: Usually Eastern European light cavalrymen that fought for the Americans during the Revolution (trained in the style of hussars from European wars). In most cases, hussars carried only swords and perhaps a pistol or two. Hussars were often used for reconnaissance and fought from horseback. You might see this abbreviated as “hus” in Revolutionary War documents.

Legion: An organization formed mostly by Loyalists during the Revolution. Self-sufficient, and usually organized on the frontier. Though most of the Legion organizations you will find fought on the side of the British, French trappers and civilians in the Ohio Valley and elsewhere formed these units to fight pro-British forces. Additionally, General Anthony Wayne – the famous Continental officer – also organized his own unit, calling it “The Legion of the United States.”

Light Infantry: Lightly armed men used as scouts and skirmishers, also used for raiding. The abbreviation “light” is sometimes seen.

Militia: A militia was the local or state military unit which was called up in times of emergency for home area defense or guard duty. Whereas most of the men who got called for duty away from home were of typical military age – a militia generally consisted of older and younger men. Militiamen were under military discipline, duty was compulsory in many areas, and men faced fines or other punishment for not appearing when called.

Muster: Think of this as a “roll call.” The “muster” was the list of a unit’s (or ship’s) officers and men. Sometimes this was broken down into “present,” “wounded,” “sick call,” “absent,” and “furlough.” The familiar term “AWOL” (Absent WithOut Leave) was not used until World War I, though some believe there was some use of it in the Civil War.

Parole: Today, the idea of parole is a different one but during the Civil War and before, it was possible that a man taken prisoner might be “paroled,” that is released to go home on the promise that they would not bear arms against their enemy until they were formally exchanged with a man of similar rank.

When the Civil War first began, neither side had provisions for the large number of prisoners they took, so many men were paroled. As time went by, however, the North began to believe that paroling Southern soldiers did two undesirable things: it returned men to the South (which had a dire manpower shortage) and it recognized the Confederate government as legitimate, which went against the beliefs of Lincoln and others. By the middle of the war, the parole system had almost completely stopped.

Regular: A regular was a man in a government funded/organized military unit. Most of these men were initially volunteers of some sort during the Revolution. They were subject to military discipline, did not choose their own officers, and were the most akin to the draftees of the 20th century.

As the Revolution wore on, the “Regular” units were the most effective and professional. You might also see the use of the word “Continental” in some military records from the Revolutionary War – this word was used mainly by the British forces to refer to these regulars. During the Civil War, regulars were many times draftees.

Temporary Commission: Sometimes seen as “Temp. Col. Joe Smith”, etc. You might see this also as “acting” followed by whatever the new temporary rank is.

This is the raising of a non-commissioned officer to officers rank or a commissioned officer to a higher rank. The commission entailed a pay raise and conveyed the authority of the higher rank. Not to be confused with a “battlefield commission,” though sometimes they can overlap. A battlefield commission can be either temporary or permanent.

Volunteers: A volunteer was someone who joined during an emergency or war to serve (generally) outside of their immediate area where there was a dire need. Generally speaking, a militiaman serving guard duty at an arsenal 100 miles from any fighting who wished to join a unit of volunteers was permitted to do, providing that there was enough local manpower. Volunteers generally picked their own officers and were not subjected to fines if they did not join.

There are two very well-known examples of volunteers in American history. First, Davy Crockett’s Tennessee volunteers who elected to fight on the frontier and, most famously, at the Alamo. The other example is Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders of 1898, cowhands and other roughnecks who were recruited by Roosevelt to serve with him against the Spanish.

So, there you have it, some of the more widely used military terms that you might run across in your research from the Revolutionary and Civil War periods. I hope it helps you with your family history.

You might also like:

- 9 Free Military and War Related Record Collections for Genealogy

- Countless Americans Never Returned Home After War: Find Their Burial Records Here

- Free Civil War Records: Discover Your Ancestors Who Served in the War Between the States

- From Pension Applications to Bounty Warrants: Free Revolutionary War Records Online

By Matthew Gaskill. Matthew holds an MA in European History and writes on a variety of topics from the Medieval World to WWII to genealogy and more. A former educator, he values curiosity and diligent research. He is currently working on a novel based on his own family history.

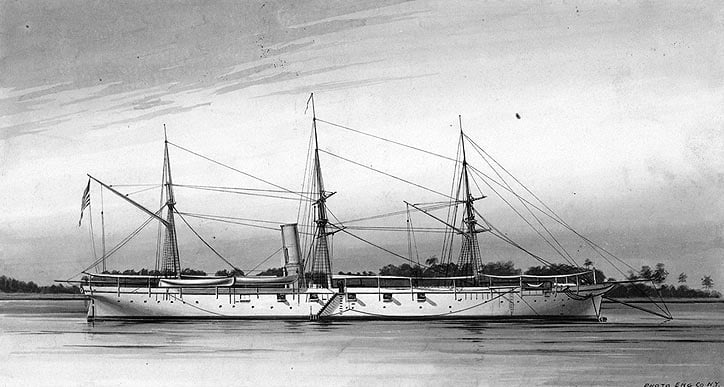

Image: USS Pawnee during the Civil War, with a spar torpedo at her bow, 1859. Wikimedia Commons.

My ancestor is listed on a pension sheet as Browne, Timothy, als Ferryman, Stephan. What does als stand for? Is it like AKA or does it mean he highered some to go in his place?

I wonder if you might help me discover this term from the Oct 10 1775 Hannastown court proceedings? This was pre-Independence and thus under the allegiance to the King of England, but the lands promised as bounty lands to many from the French & Indian War (from VA) might have also been promised by Penn’s land agent men recognized by PA courts. So I read that some families were then essentially evicted. I’m wondering if that is what this means when my ancestor was listed in court proceedings “The King vs. Patrick O’Gullion, forcible entry and detainer. True bill. Process awarded. Process issued.” Doe this mean he was evicted and essentially charged with trespassing?

I love your “abscquatulated” for thief/ another from my Northampton family was just plain “squatting” term to say you lived on someone else’s land after 7 years might become yours. Thanks for your name identifications. Carl