At some point or other in their research, every family historian will likely discover the sad fate of the 1890 census.

A critical time of population growth and change in America’s history, the 11th census of the United States should have contained the detailed records of more than 60 million individuals. But instead, we have but a few thousand left.

So what happened? A quick search will tell you that these important census records were destroyed by fire….but the whole story is much more complex, mysterious and confusing than you might have ever imagined.

Prologue, a publication of the The National Archives and Records Administration, ran this story in 1996 that details the whole string of events that lead to us losing these American treasures.

Of the decennial population census schedules, perhaps none might have been more critical to studies of immigration, industrialization, westward migration, and characteristics of the general population than the Eleventh Census of the United States, taken in June 1890. United States residents completed millions of detailed questionnaires, yet only a fragment of the general population schedules and an incomplete set of special schedules enumerating Union veterans and widows are available today. Reference sources routinely dismiss the 1890 census records as “destroyed by fire” in 1921. Examination of the records of the Bureau of Census and other federal agencies, however, reveals a far more complex tale. This is a genuine tragedy of records–played out before Congress fully established a National Archives–and eternally anguishing to researchers.

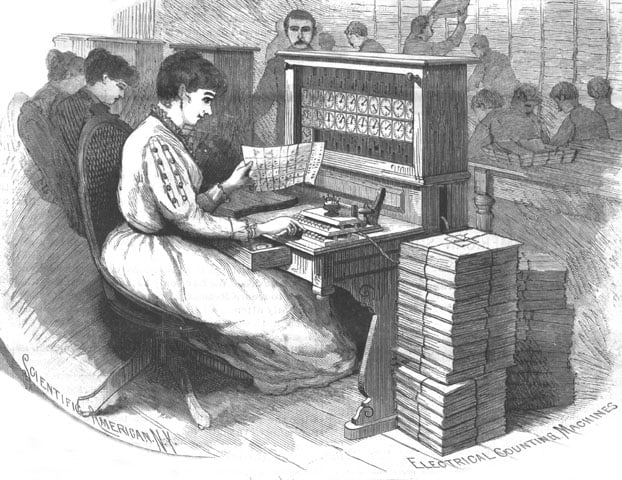

As there was not a permanent Census Bureau until 1902, the Department of the Interior administered the Eleventh Census. Political patronage was “the most common order for appointment” of the nearly 47,000 enumerators; no examination was required. British journalist Robert Porter initially supervised the staff for the Eleventh Census, and statistician Carroll Wright later replaced him.(1) This was the first U.S. census to use Herman Hollerith’s electrical tabulation system, a method by which data representing certain population characteristics were punched into cards and tabulated. The censuses of 1790 through 1880 required all or part of schedules to be filed in county clerks’ offices. Ironically, this was not required in 1890, and the original (and presumably only) copies of the schedules were forwarded to Washington.(2)

June 1, 1890, was the official census date, and all responses were to reflect the status of the household on that date. The 1890 census law allowed enumerators to distribute schedules in advance and later gather them up (as was done in England), supposedly giving individuals adequate time to accurately provide information. Evidently this method was very little used. As in other censuses, if an individual was absent, the enumerator was authorized to obtain information from the person living nearest the family.(3)

The 1890 census schedules differed from previous ones in several ways. For the first time, enumerators prepared a separate schedule for each family. The schedule contained expanded inquiries relating to race (white, black, mulatto, quadroon, octoroon, Chinese, Japanese, or Indian), home ownership, ability to speak English, immigration, and naturalization. Enumerators asked married women for the number of children born and the number living at the time of the census to determine fecundity. The 1890 schedules also included a question relating to Civil War service.(4)

Read the rest of this story on the National Archives website.

33 Billion Genealogy Records Are Free for 2 WeeksGet two full weeks of free access to more than 33 billion genealogy records right now. You’ll also gain access to the MyHeritage discoveries tool that locates information about your ancestors automatically when you upload or create a tree. Find your ancestors now.

Interested in the census for genealogy? Read our census guide.

You may also want to find out what is left of the 1890 census and how to fill the gap with other records.

Image: The Hollerith tabulator that was used to tabulate the 1890 census—the first time a census was tabulated by machine. Wikipedia.

50 or 60 years sounds more reasonable…72 years leaves few option to confirm or deny what is listed. It can also make research much more difficult for family history or building family tree research.

Thank you, Emily. There is nothing “dictatorial” about something simply because it hampers your research. There are reasons that the policy was put into place. And, when someone uses the reasoning of being a taxpaying member of the “public” which pays for a service, they usually fail to realize that so are the people working for the government who are charged with enacting or enforcing the rules.

The 72-year rule for the U.S. census started as policy and was finally codified by our elected Congress in 1978. See: https://www.census.gov/history/www/genealogy/decennial_census_records/the_72_year_rule_1.html

The 72-year rule protects privacy, thereby encouraging respondents to be truthful.

There’s nothing “dictatorial” about it.

The census is vital to every genealogist’s efforts. They are unavailable to the public, mostly for privacy reasons, until a certain number of years pass. The 1940 census was available on Ancestry.com about 60 years later. But an individual can get earlier copies to prove birth dates – I had a neighbor who got a copy of the one that counted her family so that she could get a passport. If she hadn’t told me that, I’d have had no idea. So, I’m certain there are other legitimate reasons that would allow access.

I suppose this is when the government started changing to a more dictatorial way. It has been slow, but, just look at what we have now, and the census records, I believe, are held for several tears before the public, you and me who pay for it, can see if it is accurate.