By Alice Plouchard Stelzer

The dictionary tells us that being invisible is being inconspicuous, unobtrusive, and unnoticeable. From a researcher’s point of view, tracing the life movements of invisible women creates many challenges. In the Preface to Notable American Women, editors Janet and Edward James said, “Biographies of women, especially little-known ones, pose special problems of research and interpretation. For women’s lives generally, documentation tends to be scanty.”

Here are a couple of examples of lack of documentation, even in primary source materials from public records that illustrate the challenges,

“Thomas Andrews and his wife, the relict of Oliver Clapp;” Great, now we know Thomas Andrews and Oliver Clapp were married to the same invisible woman.

Or “Nathaniel Arnold and his wife were original members of First Church.” Well, at least this invisible woman went to church.

“Mrs. Taylor, wife of Stephen, Jr., of Windsor, died in 1680.” Even in death, her name is not used. I could cite many examples of birth records that only give the father’s name, as if he did it all alone.

That leaves me with a modus operandi similar to one you see on television shows, except instead of “follow the money,” I follow the men. Even as frustrating as it is, I still can follow the men’s history to catch glimpses of the women I am seeking.

These are the challenges I am facing writing a book that tells the life stories of the women involved in settling the first towns of Connecticut; namely, Hartford, Windsor and Wethersfield. These women were not famous, did not leave poetic diaries behind and did not perform heroic deeds but were, I feel, unsung heroes who helped tame a wilderness, while birthing and rearing the children who would populate the state.

Not far into my research for my book, Female Adventurers: The Women Who Helped Colonize Massachusetts and Connecticut, I realized to find information on these women I had to try to see the bigger picture, the whys and wherefores of the culture of the time.

Public court records, although sometimes fragmentary, tedious and hard to decipher, are good resources and often, in addition to giving genealogical information, provide insight on much larger issues. When you are writing the story of someone’s life but have little concrete information, a mention in the court records can be a gem that sparks a storyline.

Discretion in the court’s language creates a challenge to historians who put together surveys using the records. Mary Holt sent out of the jurisdiction, although banishment will not show up in records as such because the court did not use the word banished. Nan Goodman in the book “Banished,” said, “All we have in the case of many of these figures is a brief entry in the record books of the General Court indicating that they were sent away.”

Probate Records have helped me many times unravel the names and generations of a family. In one instance, a probate record solved a mystery of who one woman was actually married to, when many other genealogical records had her married to three men during the same years.

Probate records also have gone a long way to convincing me that very few seventeenth century women could write because they did not sign their names when they witnessed a will. They used an “X.”

With a scarcity of primary sources that document women by name, it is necessary to use secondary sources to fill in the void. The emergence of specialized reference works, which for many researchers are too narrow, are helpful to me when prepared by 18th century authors because they were closer to the actual people and sometimes even knew a descendant. Also, some of these authors, like Royal Ralph Hinman, Benjamin Trumbull, and James Savage were interested in families, where later writers highlighted notables and businessmen.

These authors were not one hundred percent accurate but we are indebted to them for their hard work in ferreting out so much of Connecticut’s history on which other historians could build. However, they were not above doing the same as chroniclers before in NOT seeing the importance of making women visible. For example, in writing about Gov. Webster, Hinman reports, “He died in 1661 and left four sons, Matthew, Robert, William and Thomas. He also left three daughters.” He does not name the daughters as if they were not important.

We are very fortunate today that more and more reliable material has become available on the Internet. Historical and hereditary societies and organizations such as Godfrey’s Library and the New England Historic Genealogical Society are digitizing records as fast as they can. Many of the rare books that authors such as Hinman, Trumbull and Savage wrote are now available to everyone through Google Books.

Editor’s Note: Many court and probate records, as well as old books, can be found online for free using the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) and other resources. You can find our how-to on using DPLA for genealogy here and our article on locating old books online here.

One way I have kept myself in the loop of current writing about the seventeenth century was to put out Google Alerts on certain words and phrases. I used Puritans, American history, American seventeenth century and early New England. I receive an email every time there is something new online about these phrases. This clues me into interesting blogs and websites, and important books and historian authors with whom to connect.

Many records of the seventeenth century are full of contradictions. The vital facts, such as birth, marriage and death have to be laid out in a logical manner. One of the best resources any researcher has is common sense and taking the time to apply rules of logic. I am constantly asking myself, “Is this logical? Does this make sense?”

The historian researcher, after gathering all the facts available, arrives at truth through developing hypotheses by carefully assessing probabilities of different scenarios based on facts they can cite.

My hope is that readers of my book will take the time to follow the facts I found and cited and be interested enough to do some research of their own to either prove or disapprove my conclusions. We need more people researching women’s history. Maybe my book will incite readers to chronicle their own unsung heroes so that future generations can understand and appreciate their contributions.

Also read: 7 Little-Used Tricks for Finding That Missing Maiden Name

Alice Plouchard Stelzer has been writing for over 25 years as a publisher, magazine editor, newspaper editor, columnist, and journalist. She has produced hundreds of newsletters for clients and been a public relations consultant. Alice has also been a mentor/coach for writers. She has taught writing workshops on journaling, creativity, autobiography/memoir, and turning memoir into fiction. Alice is currently living in the seventeenth century while she researches and writes “Female Adventurers: The Women Who Helped Colonize Massachusetts and Connecticut.”

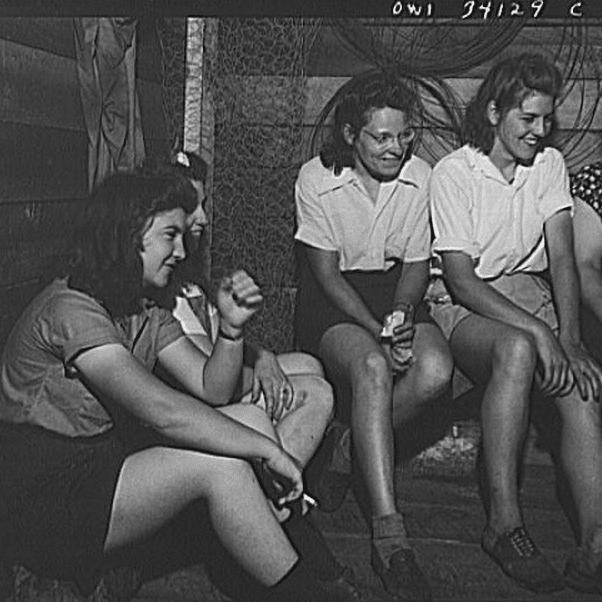

Image credit: Women workers employed by a U.S. Department of Agriculture timber salvage sawmill. Employees eating their lunch in a shed. 1943. Turkey Pond, New Hampshire. Library of Congress

This article was originally published in Feb 2013. It was reviewed and updated by the editorial staff to add additional links to free resources Feb 2017.

I am fascinated by this article as I too am searching for female ancestresses-and would like more contact with likeminded folks-thanks for all y’all do here, susan

I know all about cutting, pasting and reformatting. It’s just not worth it!!

You can copy and past the article onto a Microsoft Word Page and if you then highlight the whole text and hit the “Clear Format” button it will change it to normal type and color. If it is still too small, highlight the whole text again and change the font size (on the task bar at the top of the page). The “Clear Format” button is also on the task bar, above the color change buttons. It looks like a small piece of chalk to me, but I don’t know what it is supposed to represent.

I would love to be able to print these articles–I find it difficult to read them in the browser. I did print the artiical about ‘Researching Female Ancestors…’. However, the font size so small and the print color (pale gray) that it was just as difficult to read on paper. HELP! Margaret Ullman