A historic project in underway to bring one of the most important US record collections ever created online — and you can be part of it.

FamilySearch.org is currently working in collaboration with the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society and the California African American Museum to make the Freedmen’s Bureau Records fully accessible to the general public.

By taking the raw records, extracting the information and indexing them, they will become searchable online for the first time — providing vitally important details for those researching African American ancestors. Once indexed, searching for an ancestor will be as easy as visiting FamilySearch — previously indexed records can already be searched here.

The project is also in need of volunteers (only 9% of records have been indexed) so please consider donating your time to this valuable initiative.

About the Freedmen’s Bureau Records

[section label=”Monique Lampkin’s Story”]Monique Lampkin of Houston, Texas, discovered she was a history buff as early as seventh grade. She perfected the process of research; she loved the investigative chase for facts. Little wonder that as she aged, family history research captured her attention like no other phase of history she’d pursued earlier.“Genealogy research won my heart,” the Texas minister admitted. “It was the search for my people, an attempt to verify facts related to the oral histories that passed through the family for years.”

Last year Lampkin’s journey struck a payload of information with the examination of the Freedman’s Bank and Freedmen’s Bureau records at the George Memorial Library in Fort Bend County, Texas. The researcher traveled with her mother to discover family documents from regions in three different states.

“We were like two little girls in a candy store as we scoured through the sacred and priceless documents in an attempt to connect our lineage,” Lampkin continued. The pair located pieces of information — a child support document, a request for wages due, a character reference and additional information about the family residences. “It was simply phenomenal what I was able to locate. Now we’ve been able to share this information with other family members out in California. We’re working together to discover what’s next.”

Thousands of family history researchers had similar discovery experiences when the Freedman’s Bank records were digitized and made available for examination by FamilySearch.org in 2001. Now all of the Freedmen’s Bureau records, an estimated 1.5 million documents, will be digitized to significantly expand the research potential of those like Lampkin who want to discover their family stories.

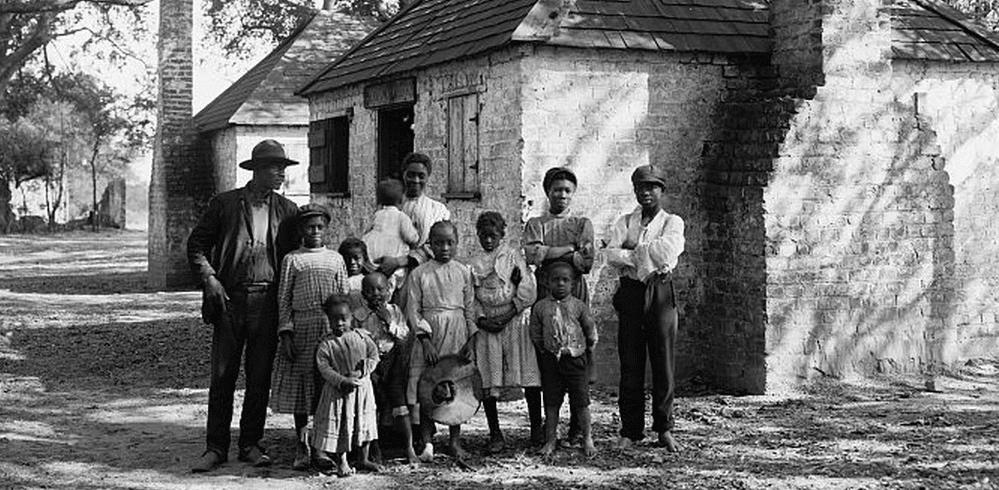

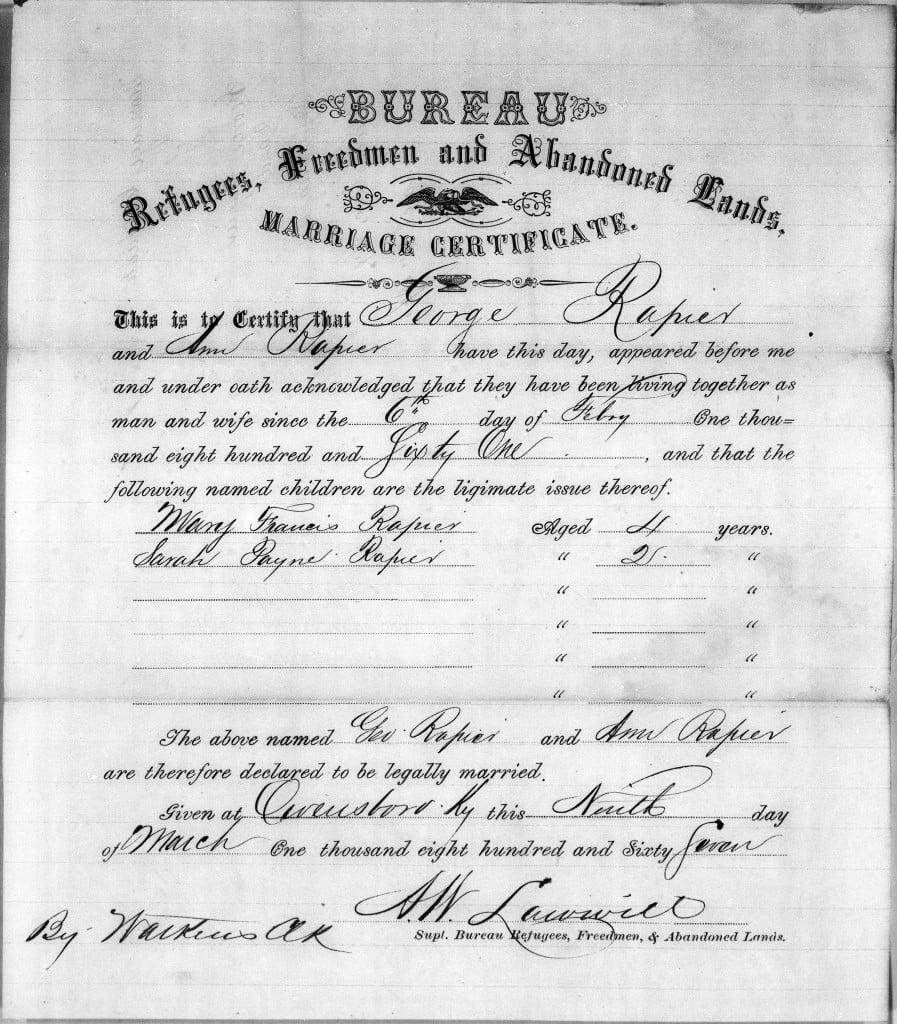

The Freedmen’s Bureau, organized by Congressional order as a result of the 13th Amendment near the conclusion of the Civil War in 1865, offered assistance to freed slaves in a variety of ways. Handwritten records of these interactions include records such as marriage certificates, hospital and patient registers, census lists, labor contracts, ration registers, indenture or apprenticeship papers and others.

The records, compiled in 15 states and the District of Columbia, appear in many different formats, according to FamilySearch collections manager Ken Nelson. “The documents are randomly organized so we need to review each one, document by document, to evaluate the genealogical information available. It’s a piece-by-piece search; the bureau records probably will not provide the whole family story but will provide clues to uncovering that story.”

Nelson uncovered clues about a pair of prominent African Americans of the time: Sojourner Truth (actual name) appeared on an employee record in the Freedmen’s Bureau War Department in Washington, D.C., and Charles Redmond Douglas, the son of civil rights activist Frederick Douglas was also employed by the bureau.

Hayes Carr, a Louisiana orphan, was indentured to A. F. Brown in an 1867 Freedmen’s document. Nelson found a second reference to the young man in the 1870 census where he was listed as a black servant. “This creates another whole set of questions,” Nelson suggested. “You don’t know where the story goes from there, but you have some clues from the Louisiana Bureau records.”

Helen Easterling Williams, dean and professor of education at Pepperdine University in Malibu, California, understands this questioning process. “For the most part, we don’t know who our family is or where our family originated,” the educator said. “We have an oral history, but to have some data points to understand it would be phenomenal. It would give me a deeper sense of my identity. Having this information digitized would be fantastic. It would bring validity to the stories that have been passed down for generations.”

Rev. Cecil L. Murray, former pastor of the First African Methodist Episcopal Church of Los Angeles, agreed. “I grew up only knowing about one generation of my family, and I always wondered about those before me, Murray said. “A door is opened when you get a chance to know your history.”

The stories of African American families following the Civil War come to life as the clues from the Freedmen’s Bureau records unfold. Future availability of these records — digitized, indexed, and accessible free online — will help direct that discovery.

As Rev. Murray summarized, “The Freedmen’s Bureau story needs to be told. … When you know your background then your foreground pretty well takes care of itself. When you know where you are coming from then you can design where you are going.”

[section label=”Fast Facts”]10 Facts About the Collection

• The Freedmen’s Bureau was organized near the end of the American Civil War to assist newly freed slaves in 15 states and the District of Columbia.

• From 1865 to 1872, the bureau opened schools to educate the illiterate, managed hospitals, rationed food and clothing for the destitute, and even solemnized marriages. In the process it gathered priceless handwritten, personal information on potentially 4 million African Americans.

• In 2001, FamilySearch indexed the Freedman’s Bank records, comprising more than 460,000 historical records, which became one of the largest collections of searchable Civil War-era African American records.

• In 2009, FamilySearch volunteers continued these efforts by indexing over 800,000 Freedmen’s Bureau records from Virginia.

• Today, FamilySearch is launching a call to action to index the names of freedmen and refugees from approximately 1.5 million more documents in the bureau collection.

• Using an online indexing tool, volunteers will mine each record for data, which will then be compiled into an online searchable database.

• Nationwide volunteer indexing efforts are expected to take one year to complete.

• Once the records are indexed and searchable online, many African Americans will be able to discover their Civil War-era families for the first time.

• Records, histories and stories are available on discoverfreedmen.org.

• Additionally, the records will be showcased in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, which is currently under construction on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., and expected to open in late 2016.

[section label=”Access Records and Get Involved”]To find out more about the Freedmen’s Bureau Records, to access those that are currently available online, or to help with indexing please visit DiscoverFreedmen.org.

All images and information from DiscoverFreedmen.org.