Are you ever asked the question What is My Family Crest? Or perhaps you already have a crest in your family tree? Find out why, according to Jack Turton of The Coat of Arms Database, “family crest” is a misnomer and how to understand the actual meaning and history behind these symbols.

When people talk about a “family crest” they usually mean a coat-of- arms belonging to a family member who was “armigerous” – meaning he or she had the right to display one, which in turn implies noble (or at least gentry) status. But, too often, coat-of-arms are erroneously assigned to entire family line or surname in a family tree.

Do I have a family crest?

We know about historical coats-of-arms because they functioned a bit like modern trademarks. They were administered by a college of professionals called “heralds,” whose records survive in museums and archives. Individual families also kept track of their own history and heraldry.

In the 19th century it was common to publish the results in weighty volumes of family history, many of which are now available in online archives. Around that time, a growing interest in genealogy sparked the publication of massive biographical encyclopedias such as Burke’s Peerage in the United Kingdom, Rietstap’s and Dizionario Storico for Italian heraldry, and Armorial Lusitano for Portuguese.

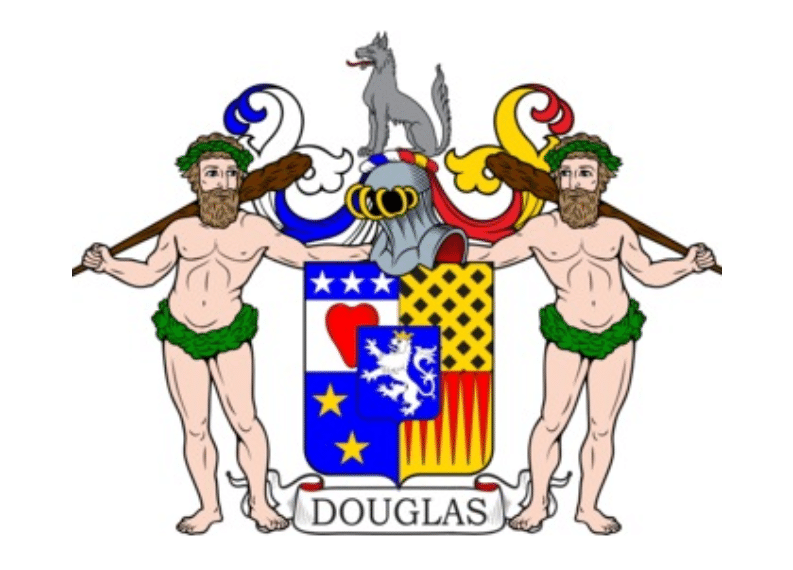

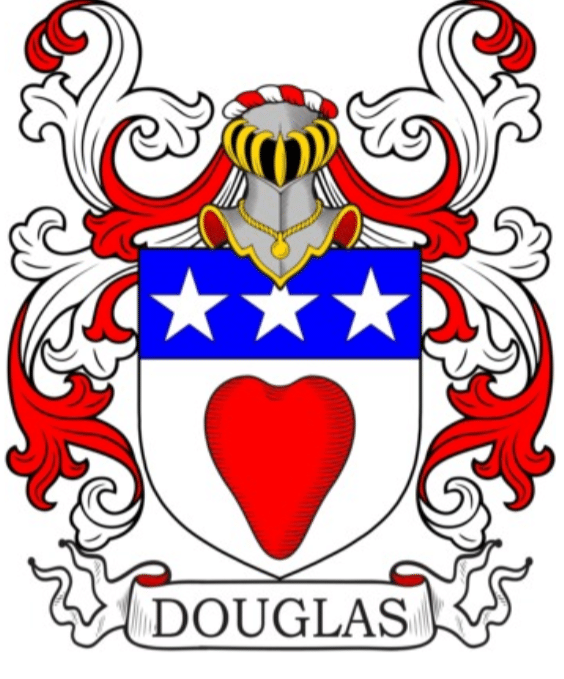

For example, here is the coat-of-arms of Sir James, the Ninth and last Earl of Douglas, who lived and died in the 15th century.

Medieval nobles and gentry (armigerous individuals) left their mark not just in the old chronicles, but in legal and government documents, many of which are available in 19th century translations. For example, the English Inquisitions Post Mortem recorded who owned what on their death, and the Close Rolls recorded who held which public office – and since each county had a sheriff and various magistrates most local notables appear somewhere in these pages.

Thus, a little legwork will often tie a coat-of-arms and a name to an intriguing personal history and career. The coat-of-arms is then revealed to be a visual DNA, telling us not just who the bearer was in his world, but also where he came from. As it happens, the life of Sir James Douglas, whose arms we have just contemplated, is well-documented.

Sir James was a member of the famous Scottish Douglas family, whose history helped inspire the Game of Thrones (for example, his father was murdered in something rather similar to the “Red Wedding.”) A Knight of the Garter, Sir James was captured fighting against his own king in 1484, and relegated to a monastery where he died in 1488.

If “Douglas” is your surname, then you might be related to him. The population of Scotland was under a million back then so being a Douglas really did mean you were a member of the Douglas family.

Looking at Sir James’s coat-of-arms, you immediately see that it comprises a shield, supporters left and right – in this case the two “savages” – and an actual crest: a wolf. The crest may have been worn on a helmet, especially in tournaments.

The “device” on the shield is what James would have displayed in battle and tournament: on his shield, if he carried one (not a certainty by this era, since by then knightly weapons were often two-handed), perhaps on a heraldic tabard if worn over his armor, and maybe painted onto his armour like a badge. This would have marked him out as a man of noble birth. It would also identify him to anybody who could read the heraldry.

When did coats-of-arms first start to appear?

Coats-of-arms began in the 12th century as a way to recognize combatants and followers in tournament and battle. Even before they had visors, knightly helmets tended to obscure people’s faces; especially if viewed from a distance, or through the red mist of combat. Knights wanted to broadcast their membership of an elite and increasingly exclusive caste. They needed to ensure recognition for any deeds that they performed and also to identify themselves as somebody you would capture to hold for ransom, rather than slay out of hand.

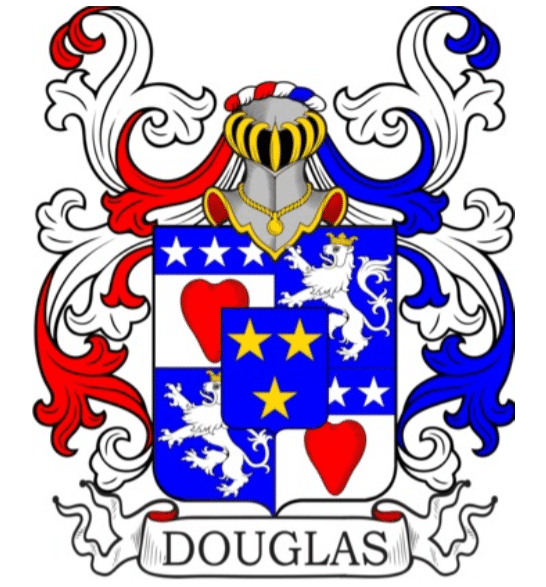

However, by the 15th century, coat-of-arms were becoming too complicated for this purpose. In this case, the heart and stars (top left) indicates connection to the Douglas family, but there were several branches of the family and they did not always fight on the same side!

For this reason, powerful lords tended to pick a distinctive element of their personal coat-of-arms and use it as a badge with which to identify themselves, and their friends and followers.

For example the English earl, Warwick the Kingmaker, issued his followers with “bear on a ragged staff” badges. Our Sir James could have chosen to use the Wolf from his crest or perhaps a “savage,” or a combination of both. In adopting simple badges, lords were returning heraldry to its roots in knightly combat.

The reason why coats-of-arms had become complicated is that they were used to display a specific individual’s lineage, marriage and other connections.

Here’s the technical description of Sir James’s arms from the Coat of Arms Database, using the language of heraldry derived from Medieval French and a smattering of Arabic, and standard abbreviations:

Quarterly, 1st, Douglas, as above; 2nd, sa. fretty or, for the Lordship of Lauderdale; 3rd, az. three stars or, for Murray, of Bothwell; 4th, or, six piles gu. for Brechin; en surtout, az. a lion ramp. ar. crowned or, for Galloway. Crest—A wolf sejant ppr. Supporters—Two savages with clubs in their exterior hands ppr.

Symbols and Structure in a Coat-of-Arms

Coats-of-arms are usually built from a limited pool of symbols, much like the emoticons available on social media: here’s a visual glossary of heraldic symbols. Though many of them seem abstract, most have a well-known meaning.

The Lion, for example…

…represents, among other things, Deathless Courage.

The Eagle…

…generally speaks of high honor, or even Imperial connections or pretensions.

The Fleur-de-lis…

…is associated both with French royalty and the Cult of the Virgin Mary. It can also indicate that the bearer of the coat-of-arms is the sixth son.

Though it’s common to attribute these meanings to the 19th century Romantic Movement, most do in fact go back to the Middle Ages when almost everything had symbolic significance. We can see this, for example, in Medieval bestiaries which devote most of their space to proverbs about particular animals and also in Medieval fencing treatises such as Flos Duellatorum, which urges the swordsman to have the courage of the fox and the stability of the elephant.

So, when we look at Sir James’s coat-of-arms, we can decode both the symbolism and the story it tells. The first part of the heraldic description (shown above) describes the shield which is broken into quarters, numbered typewriter-style, top left to right, bottom left to right:

“1st, Douglas, as above” refers us to the arms of William, 1st Earl of Douglas:

Guillim, a 17th century heraldic author, believes that the heart shows the holder to be a “man of sincerity…who speaks truth from his heart.” However, its presence here probably also commemorates the heroic death of the first Douglas earl’s uncle, Sir James the Good, who fell while taking the heart of King Robert the Bruce on crusade (the episode is described in the 14th century Froissart’s Chronicles).

Prior to that, the heads of the Douglas family probably bore a simple white shield with a blue bar displaying three stars (technically: argent, on a chief azure, three stars of the first). This was a good example of a basic, and thus easily recognizable, coat-of-arms from a much earlier period. It had probably passed from father to son since the mid 12th century.

Guillim says Stars are “emblems of God’s goodness.” Knights very much wanted God on their side, and at the same time regarded victory as proof that He was indeed so. This choice would have been a fitting one for a bellicose Douglas.

Thus, the first quarter of the shield enables Sir James, 9th Earl of Douglas to tell the world: that he is a Douglas; that he is related to the legendary Sir James the Good; that he speaks his mind; and that God is on his side.

The second quarter (with abbreviations expanded) is 2nd, sable fretty or, for the Lordship of Lauderdale. The heraldry translates as, “black diamonds on a gold background” and references his ownership of the strategic border lordship of Lauderdale, land originally granted to one of his ancestors.

The Fretty…

… according to Guillim represents a net and symbolizes skill in the art of “persuasion,” not something one would normally associate with the warlike Douglas family. Perhaps it actually references fishing rights on the River Leader that runs through Lauderdale.

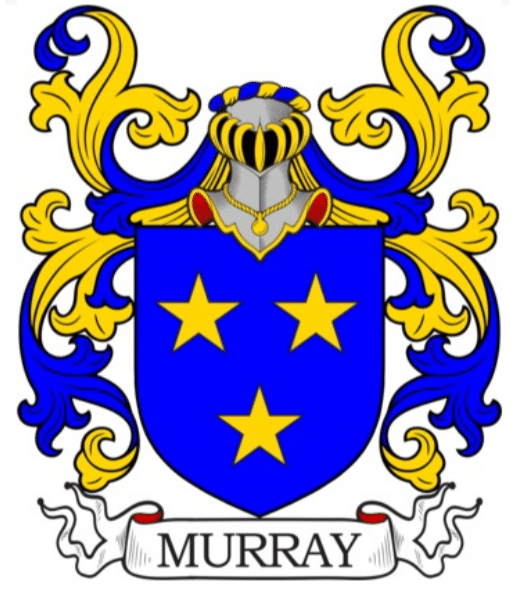

The third quarter (3rd, azure three stars or, for Murray, of Bothwell) meaning, “blue background with three golden stars.” This is the coat-of-arms of Sir James’s mother’s family, Murray of Bothwell:

It appeared in the family coat-of-arms when Sir James’s father (another James, known as “the Gross”), married Joan Moray of Bothwell (spellings of surnames were not standardized back then).

“Quartering” of coats-of arms, as it was termed, was a standard way to advertise the union of two aristocratic houses. It reminded the world that Sir James could call on the loyalties and the resources of both Douglas and Moray families, including their supporters (historians use the term “affinity” to describe such clan-like groups).

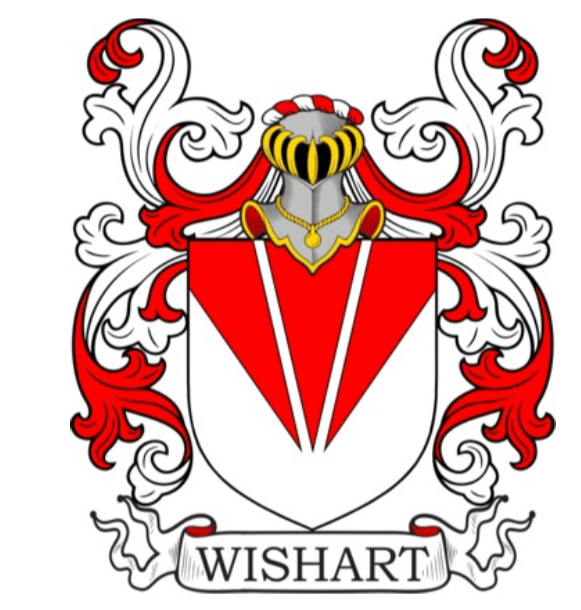

Now we come to the final quarter (4th, or, six piles gules for Brechin) meaning “gold with six triangles in red.” The symbolism appears lost in the mists of time (could they represent pennants?) and their presence on this coat-of-arms is a mystery!

They are often said to derive from the arms of Wishart of Brechin and relate to Ettrick Forrest:

However, at least one venerable heraldic history argues that they actually relate to the Douglasses of Lochleven. Either way, James was probably drawing attention to a family connection.

At last we come to that big central shield (en surtout, azure a lion rampant argent crowned or, for Galloway) meaning, “above all, blue with a silver lion rampant with a gold crown.”

We already know the Lion as a symbol of Deathless Courage. The Galloway lion first appeared in the second and third quarters of the arms of Archibald the Grim, 3rd Earl of Douglas. Archibald was the swashbuckling “natural” son of the Good Sir James, and a keen exponent of the two-handed sword:

A loyal follower of the king, Archibald was appointed hereditary lord of Galloway, a (justifiably) rebellious province and former kingdom – hence the crown – that had originally belonged to the Balliol family.

Finally we come to the Wolf (A wolf sejant proper. Supporters: Two savages with clubs in their exterior hands proper). The Wolf may reference Rome, perhaps Sir James had made a pilgrimage there, or may have been selected to broadcast the wolfish nature of its bearer. He may have picked the Savages, or Woodmen, in reference to his family’s Ettrick Forest connections, or perhaps because they were dangerous looking men with clubs. So this is heraldry, but it may also be the 15th century equivalent of a biker jacket.

So let’s take another look at Sir James’s coat-of-arms:

It says something like…

I’m a Douglas, member of an important family, descended from a legendary hero. I speak my mind, and God is on my side.

I’m powerful in my own right: I have my own connections through my mother; and I am a mighty territorial lord as well.

If you see men displaying Savage & Wolf badges, they’re mine, and if you are fighting on the other side, watch out!

Nobody living has the right to bear these particular arms as their own.

That’s why you shouldn’t ask the question “What is my family crest?” and instead ask “Did any of my ancestors have a coat-of-arms?

As we have seen, this coat-of-arms, like all other personal arms, belongs to only one individual from one time and place. It contains a crest, but is neither just a crest nor a “family crest,” nor a family anything else.

Beware of websites that try to tell you otherwise. The might encourage you to find your own family crest, making the process seem straightforward and simple, and then sell you goods based on this “find”.

A good test for a well-researched website on finding a coat-of-arms or crest is whether the site displays more than one coat-of-arms for each family. (Our site, the Coat of Arms Database, has 49 for the Douglasses alone!)

However, there’s nothing wrong with doing as people in the past did and celebrating your ancestors by displaying their coats-of-arms around your home. It’s even better if you can point to them and explain the story told by the heraldry, and recite the deeds and adventures of those who have gone before.

You can get some help deciphering coat-of-arms in your tree here.

Jack Turton is an English contributor to the Coat of Arms Database. His ancestors plied their longbows in the service of Henry the Fifth.

Interesting article. Thank you for sharing.