By Bridget M. Sunderlin, CG®

You know that you have become an intermediate researcher when you suddenly have a thirst to read original documents – such as land records, petitions or wills – that involve your ancestor.

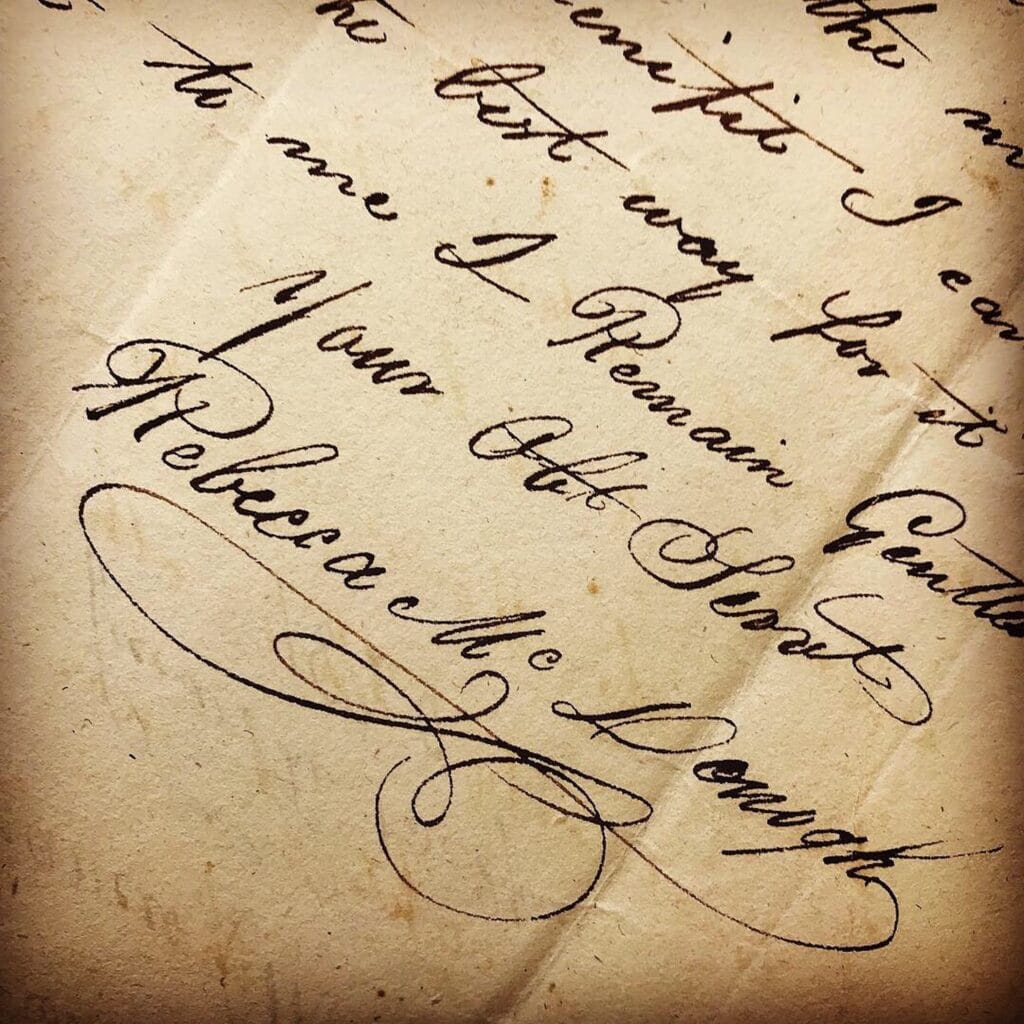

I can honestly say that having held a petition written in 1820 by my 4th great-grandmother, and seeing her signature at the bottom, brought me just as much joy (if not more) than had I seen her photograph.

Depending on the condition of the document, its date and the handwriting therein, these joyous finds can be beyond frustrating to read. Upon first glance, they seem to have been written in a foreign language, even though you know they are in English.

This document from 1829 was a bear to transcribe.

But there is hope for making sense of these originals, if you know the right techniques to use.

Here are Some Tips to Make the Job of Reading and Transcribing Old Documents Easier

Tip #1

Take Advantage of Transcriptions, But Always Look for Originals as Well

33 Billion Genealogy Records Are Free for 2 WeeksGet two full weeks of free access to more than 33 billion genealogy records right now. You’ll also gain access to the MyHeritage discoveries tool that locates information about your ancestors automatically when you upload or create a tree. Find your ancestors now.

Transcriptions are created by genealogists and family historians to copy an original document, removing the handwritten element. This process can make it easier for you to read and understand the original – and you may even feel that you don’t need the original if you locate a transcription.

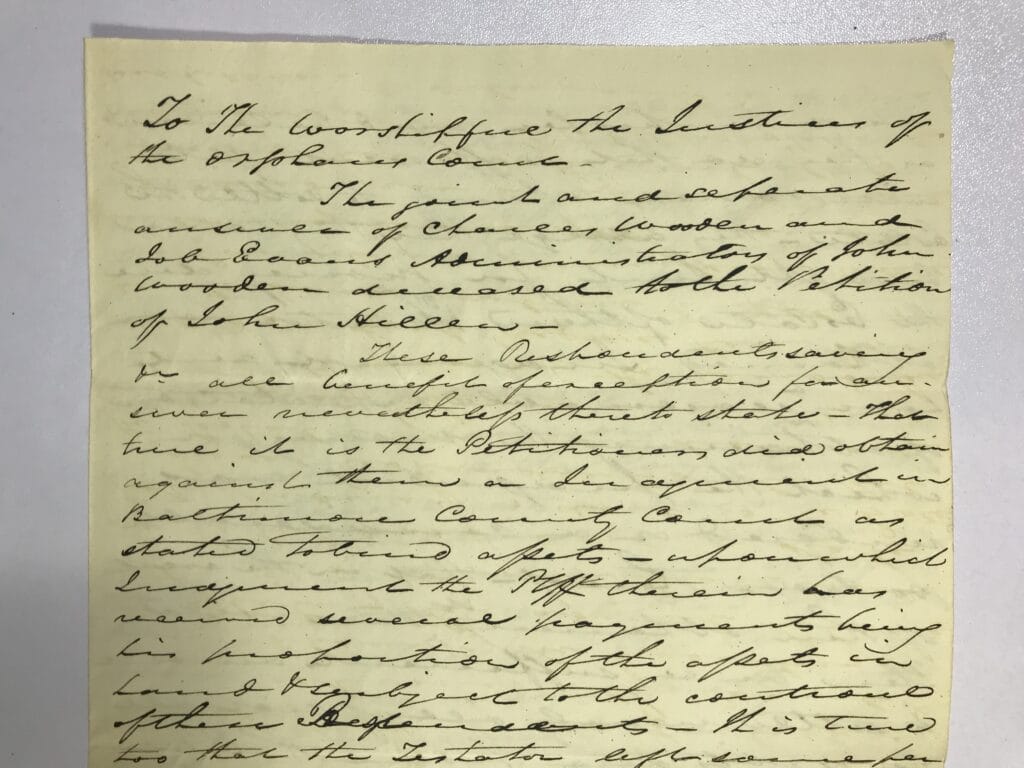

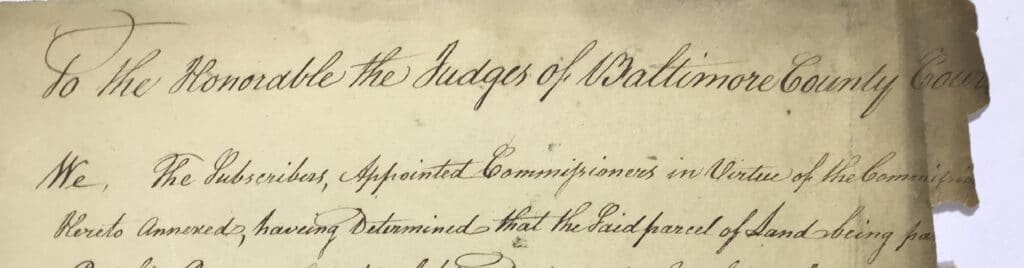

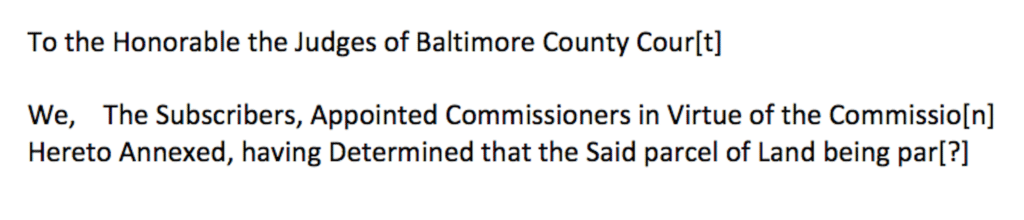

An original 1796 petition vs a transcription of the original, below. Note that the standard square bracket [] is used by genealogists to identify comments they add, which were not within the original. These highlight illegible text, unknown words and smears.

But a transcription can, sometimes, remove the context under which the document was found, or even contain errors.

When you find an old document, first see if a transcription exists. If it does, always compare it against the original. Allow the transcribed passage to aid in your reading of the original record, rather than replace it. This important step will help you gain a deeper understanding of the document and catch any errors that may have taken place during the transcription.

Here is an example of how important original documents are, even when microfilm and transcriptions are available.

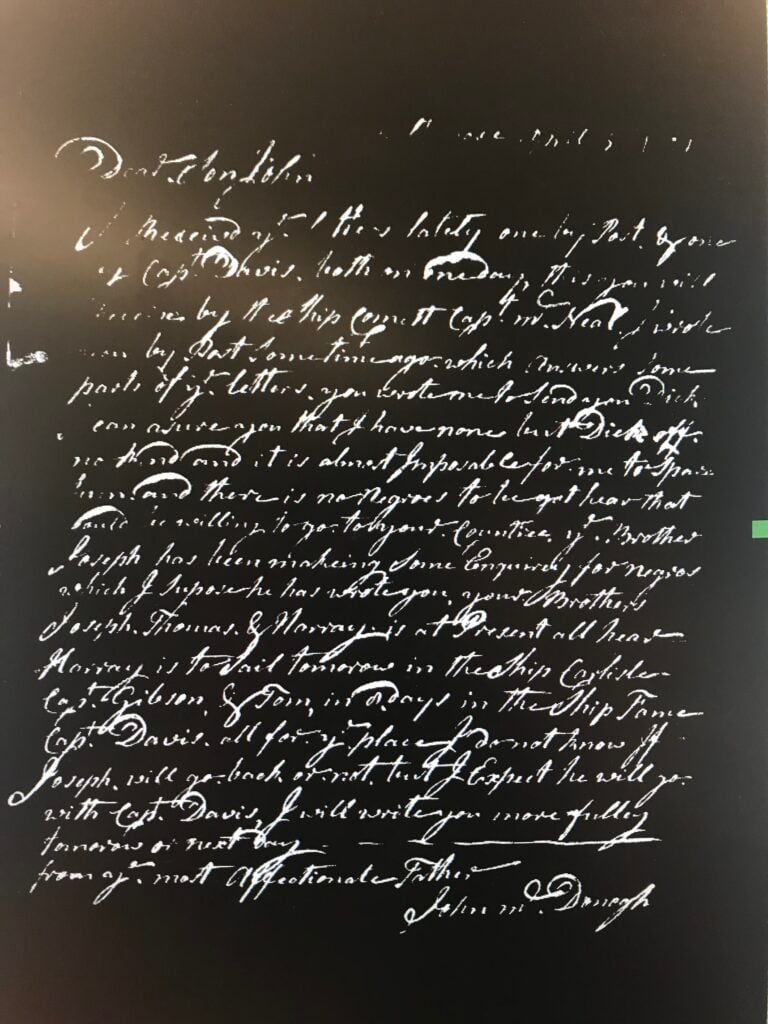

When attempting to locate letters sent from my 5th great-grandfather to his son, all that I could find locally were microfilms. Excited, it wasn’t until I saw their smudged condition, that I realized they were nearly illegible. This made transcription impossible.

To my surprise, these films were not only smudged, they were also shot in reverse, with white lettering on a black background. This technique was often used to increase legibility through contrast. This makes each letterform bolder, and is especially effective with thinner pen strokes.

Reversed microfilm of an original 1804 letter.

However, the effort added very little to the readability of these letters.

Several weeks were spent in vain, attempting to transcribe these microfilmed letters that included intimate details of my 4th great-grandfather’s life. I was under the mistaken impression that these were the only copies still available.

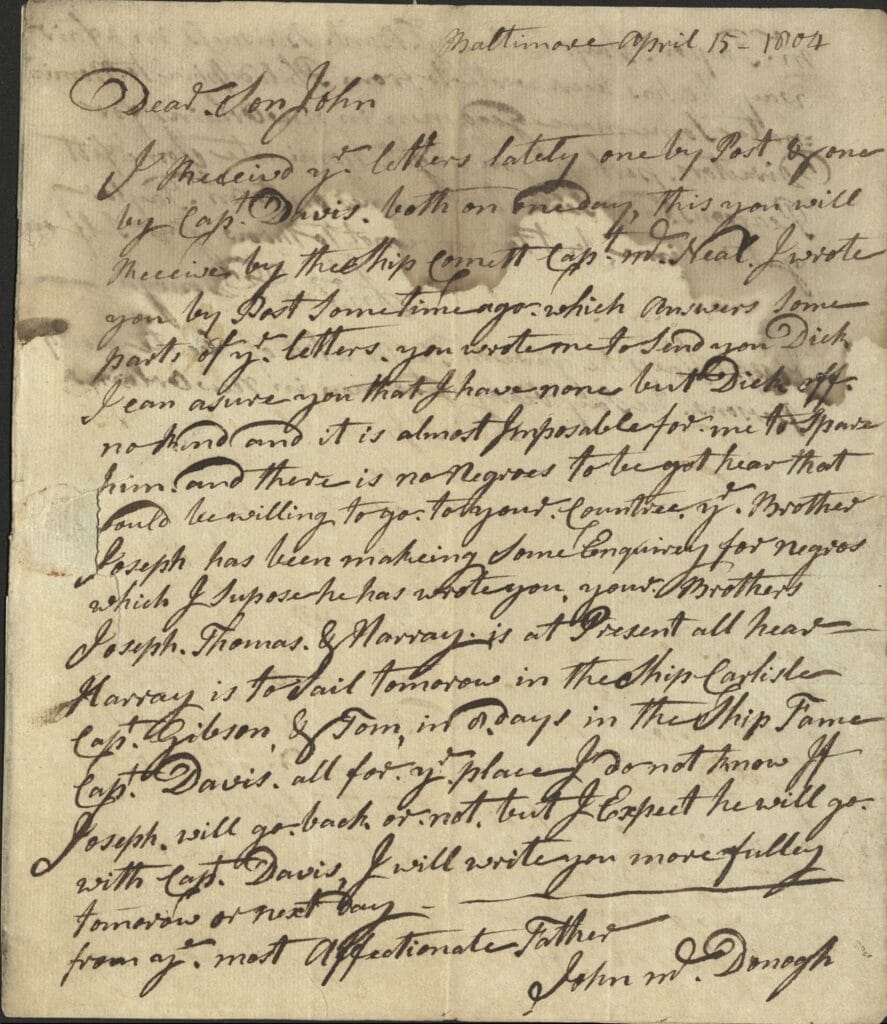

Further research however, led me to find the original letters. Once I was able to locate a digital copy of the originals, I could actually read them! They were not transcribed of course, but the improved quality was worth the second research trip. Once I was able to transcribe the letters from the newer digitized images, I unlocked a few family stories I would otherwise never have found. Learn from me. Make every attempt to compare originals whenever possible.

Digitized copy of an original 1804 letter.

Tip #2

Don’t Zoom In…Zoom Out

Family researchers can be as hyper-focused as a dog with a bone, looking for only one ancestor at a time. In the genealogical world, we might call this approach extraction. When you extract information from a document, you pull only one specific piece out. You might use this approach when attempting to find a baptismal record for your ancestor. It can feel like discovering the diamond in a sea of crystals. Beware, though. This methodology has its flaws.

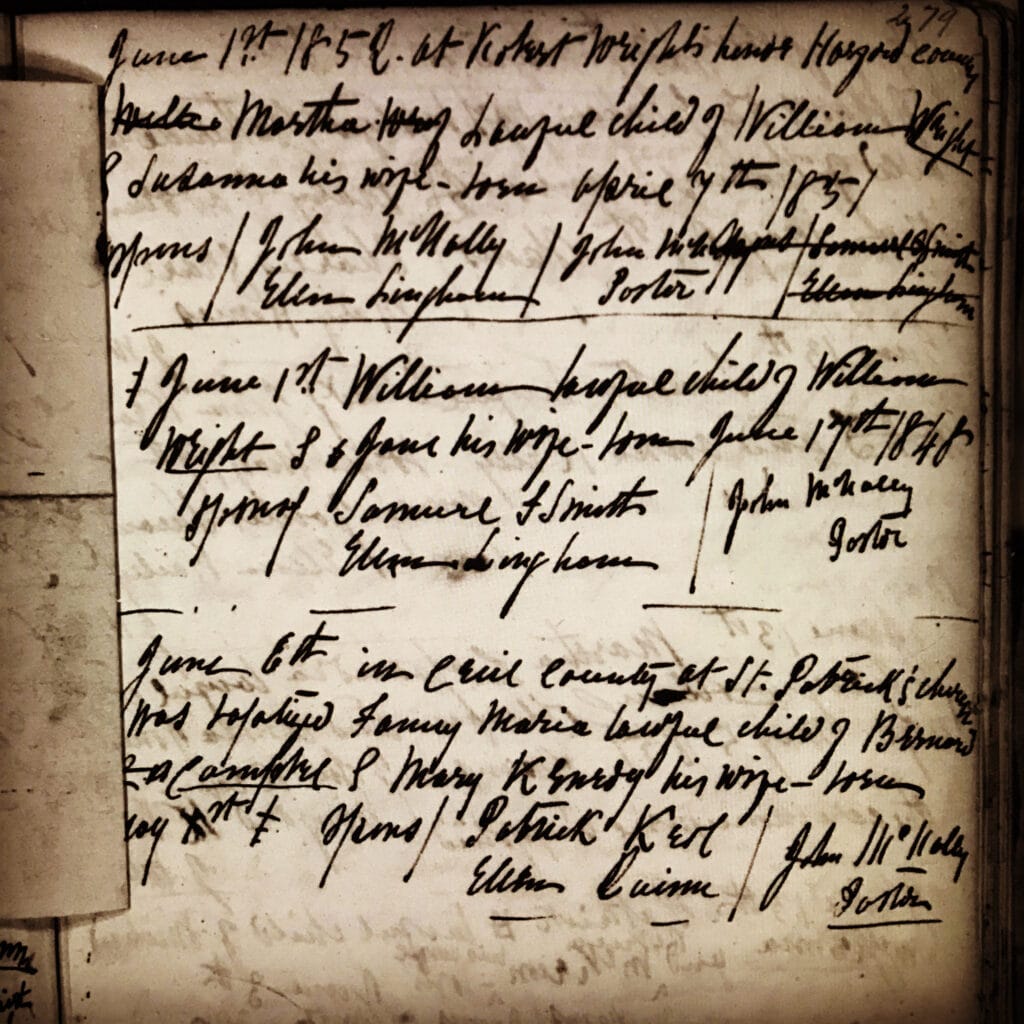

Your focus should begin by locating that specific baptismal record. Your next step should be to zoom back out. What other records surround your ancestor’s baptism? Is there an entry above or below that includes other family members? I can honestly state that had I not looked at entries above and below my 2nd great-grandmother’s baptism, I never would have seen her brother’s baptism directly below.

Sometimes there are two diamonds among a sea of crystals. The top entry is Martha. The next entry is her brother, William, from June, 1852.

Tip #3

Read the Document Out Loud

Become better acquainted with the original document by attempting to read it out loud. Read it repeatedly to get an even better understanding. While doing so, ask yourself a few questions. Can you read it easily or are you stumbling on certain words? Are you able to understand the document’s purpose? Does it stand alone as a document or might it be in response to another document that requires further research?

By reading the document out loud, you will be able to clearly think about the information you are reading. This technique forces you to read every word and not jump around the page as you might do while scrolling through a newsfeed on your computer screen. By reading the document a few times, you should begin to become more comfortable with the handwriting of the scribe.

Tip #4

Type it Out – One-Letter-at-a-Time

It goes without saying that as you begin to copy word-for-word, you immediately hit a snafu. Boom! What does that word say? This is the struggle of every transcriber. When you meet with this obstacle, it’s best to type it out, one-letter-at-a-time. If you still can’t make out the word, try running it through an editing program. Perhaps then, the word will become clear.

Tip #5

Run it Through an Editing Program

Scan or photograph the original document to make it easier to read and then turn the document into a jpg image so that you can edit it in your computer’s photo-editing software. The image can be cropped, enlarged, sharpened and even reversed. Any of these techniques can be easily employed by anyone who owns a computer by using a program such as Photoshop or via an online program such as Pixlr. These techniques will allow you to more easily distinguish the unique characteristics within the document.

Tip #6

Use Historical Context Clues

Always take a moment to place your document in history. When was it created? Why was it created? Who created it? What was its purpose within its specific time in history?

Be aware of what you are looking at. If it’s a record within a parish registry book, investigate its cover. See if there’s a contents page. Identify the date range of the entries. Determine if the records have been written in one hand or more than one hand. If the original is a petition within a packet of several probate documents, review all of them. Identify each document’s date and purpose.

Tip #7

Use Handwriting Clues

With the advent of the digital world, it’s safe to say that many who research genealogy may not have been taught to write in cursive lettering. Not to worry! Plenty of resources exist to assist your readability with passages of handwritten text.

Start by reading through this help article which is packed full of tools and then visit Ancestry’s Tips for Reading Old Handwriting, which will help you to visualize the many different styles of cursive lettering.

FamilySearch has several guides including their Language Resources and Handwriting Helps page. There are a few books you may wish to consult or purchase if you want to learn more. Begin with Kip Sperry’s Reading Early American Handwriting. If focused on Colonial Handwriting, see Harriet Stryker-Rodda’s Understanding Colonial Handwriting.

Handwriting styles are unique to the writer. Use this idea to your advantage by reviewing multiple passages penned by the same writer, if you can. By doing so, you will begin to see patterns and stylistic approaches to their letterforms and spelling. Decode the writer’s handwriting style. Do they use long dashes or avoid crossing their t’s? Do they embellish letterforms? Is their slant exaggerated? Use the document itself to decipher all letterforms and words. This will build your fluency with this writer, allowing you to read their passages with ease.

Tip #8

Practice Through Volunteerism

One of the very best ways to improve your transcription skills and increase your fluency with reading historical documents is practice, practice, practice. Becoming a volunteer transcriber is the best place to start. Check with local opportunities first, such as digitization projects at your local archives.

If local options are lacking, branch out to one of the many online options available. You can be a Citizen Archivist at the National Archives. The Library of the Congress would love for you to become a Virtual Volunteer. The Smithsonian has dozens of projects available to you as a Volunpeer. FamilySearch would love it if you served as a document Indexer. Test your skills by indexing photos of gravestones at Find A Grave. Or sign up today to transcribe at From the Page.

Be a friend and always remember to share your transcriptions with your genealogical cousins. Check out this article which identifies ways to add your transcriptions to your tree on Ancestry. If you want to move your skills into those of a professional genealogist, visit the Board for Certification of Genealogists’ Document Analysis Skills page and test your new skills as a transcriber.

Let’s clear up one final misconception about transcription. As amazing as Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software programs are, they simply cannot recognize the distinct qualities of handwriting. Perhaps one day soon they will meet with success, but as of yet, we are still left to our own eyesight and detective skills to transcribe historical handwritten documents. Consider it part of the fun of being the family history detective!

Bridget M. Sunderlin, CG® practices in Maryland. She is the owner of Be Rooted Genealogy, where she specializes in Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York, Ireland, and Scotland research.

Thank you for your great question, John. A true transcription should be written verbatim. This includes punctuation, spelling, spaces, underlining, added words, and returns. This can be challenging based on present-day keyboard limitations. The transcriber is free to add [bracketed] information to assist with readability, especially as it pertains to context or content. For example, if a word is written in error, a transcriber might add [sic] directly next to it, to identify it as such. For example, if the subject’s name was actually Eleanor Wooden, but midway through the document it was written as “Emma Wooden [sic].” Some transcribers also use [sic] for misspellings, but this could get overused if the passage is dotted with spelling errors. The transcriber should then include a note that all bracketed information are notes authored by the transcriber. The goal of a transcription is to create a verbatim duplicate of the original, while an abstract is meant to remove unnecessary boilerplate and jargon, making the passage more easily readable and understandable to present-day readers.

Great article! Very helpful with excellent referrals to other documents. One question I have struggled with related to the fact that when transcribing old documents, I often find spelling errors and also words that are spelled differently from today. Should the document be transcribed verbatim or should spelling be corrected or unusual words put into their modern form for easier understanding of other readers?

This article on transcription was wonderful. Thank you for sharing it. This basic skill is often overlooked. When I slowed down to transcribe documents, I finally started studying record types. I was very dependent on Ancestry.com hints for years. Now they are just a bonus, and I have found that many of them are a detriment.