This lesson about research logs is part of our online Organization for Family Historians course. To access the entire 36 lesson course, associated hands-on activities and quizzes, and digital workbook (which includes a fillable research log) check out our Course Center.

Have you ever excitedly visited an online research site (or physical archive) and considered with awe the vast collection of records available to you, but had no idea where to begin your research? Or, perhaps, you’ve spent hours researching a single person only to lose or forget much of what you learned and where exactly you learned it. Maybe you’ve even walked away from your research for a few weeks and then been completely confused about where to pick it up again when you returned?

This has happened to most of us, and it absolutely will happen if you don’t use a research log. Research logs have long been one of the most important tools for the organized genealogist, for good reason.

What is a Family History Research Log?

It’s a document that tells you what you’ve researched, what you’ve found, what you didn’t find, and what research you still need to tackle on a person or family group. They are sometimes printed out – but can also be found in fillable, digital form like the one included in our Family History Workbook.

When you use a research log during your genealogy journey, your research is always moving forward and you’re not wasting precious time and expense retracing your steps, doing the same search over and over or, of course, standing in the middle of a repository with no clue what to do next.

Genealogy Without a Research Log = Insanity?

These days it’s super easy to pull up your ancestor’s profile in your online system, hit the “Search” button, and click in and out of the hundreds (or thousands) of records that magically appear on your results page. Along with hints, this search process can uncover a lot of obvious records that you’re pretty sure belong to your ancestor.

If you save that record to your tree, the system adds not only the information you’ve selected to pull from the source, but also a neat little source citation and image of the original record (if applicable). That’s all well and good, but it’s not actually how thorough genealogy research should be conducted. Theoretically, you should search for one life event or fact for one family or ancestor at a time.

For example, you see that the birthdate and birthplace for your third-great-grandfather is blank in your family group sheet (see the previous lesson). Your task at that time should be ONLY to search relevant sources for that person’s birthdate and birthplace, not everything you can turn up about his entire life history.

When you’re armed with a research log, searching for a birthdate and birthplace won’t be daunting or distracting. Your log will remind you of the ancestor you’re researching (third-great-grandfather Andrew Williams) and the objective of your research (find Andrew’s birthdate and birthplace).

You will list which sources you’re going to research (county censuses for specific timespan, births and christening indexes, baptismal records, etc.). Once you’ve searched one source, you write down what you found, including an accurate citation of the source. That way, the next time you work on this same objective you won’t duplicate your efforts.

In this way your research log becomes an index to the research you’ve already performed; something you can refer back to anytime you’re researching that particular family group. You’ll know when you researched, what you looked at, what you found, and be able to easily plan what to do next.

You’ve probably heard that the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and getting the same results. Research logs can keep you from driving yourself crazy!

Where Can I Find a Research Log?

As with other genealogy forms, there are multiple variations of research log templates, and you can always create your own custom version with features you’re most likely to use. The template we’ve included in our digital workbook in our Course Center can be used for the purpose of tracking a specific objective (such as finding parents, an occupation or the location of a birth place and location) or for a more general search for a specific ancestor or even a family group.

It includes the following spaces:

- Your ancestor’s name

- The objective of that research

- Date of your search

- Collection searched and its location

- Discoveries based on the search of that collection

- Your objective outcome

- Notes

Getting Started With Research Logs

If you’re taking our Organization Course as a beginning genealogist, you have the supreme advantage of being able to start off fresh with your new organizational plan and blank research tools. If you’re an advanced or long-time family historian with stacks of photocopies culled from decades of research, you may be questioning whether research logs are a realistic option.

Our recommendation for those who’ve never used a research log before is to start now and go forward, but don’t try to go back and recreate previous research efforts. Once you organize your paper and digital information into family group files, you can create a research log for individuals or groups as you conduct research on a particular family.

Ready? Let’s begin!

Before You Research

A research log is just as important to your research plan as it is for recording your results. Before you visit a repository or go online to search a database, take a moment to start your research log. Go ahead and fill in the date you’re researching, the purpose/objective of the search, and most importantly, the sources you know you need to search.

Knowing sources you’ll need to review will require planning and some preliminary research. Most libraries and archives offer a listing of their resources on the facility’s website or in an online catalog. This step will also save you a wasted trip to a facility that doesn’t hold the records you need to search.

You’ll also want to write down how you plan to achieve the results you need, and the questions you’re asking. Questions like, “Who are Charlie Malone’s parents?” and “Why was the Malone family in Chambers County in 1880?” remind you of your purpose when you’re tempted to scamper down a rabbit hole.

If you need help developing research questions that will help you complete your research objectives, please review the Developing Research Questions section of our Master Course.

Results and Negative Evidence

Another goal of your research log is to show the results of your search, whether those are positive or negative. Negative results are just as important as positive finds. If you thoroughly search a source and don’t find your answer, then you’ll know not to search that source again.

As you conduct your research, using your research log as a guide, make notes of your results in the designated column. Your method for recording results can be a simple comment or a system of symbols — it’s up to you.

Here are some examples often seen in research log systems:

Positive results — Name of person found or event, the document number you’ve assigned to the results (if you’ve made a photocopy), or the family group file name the results belong to. You’ll also want to create a footnote citation for this source right away while you still have the source (and all of its pertinent information) in front of you.

Negative results — The word “Nil,” the Ø symbol, or for best results, what you were searching for and didn’t find, such as “No adult males aged 25 to 35 named Williams.” When you don’t find something, you might also make a note to do some future research in a different type of record or another area to search — maybe even in a neighboring county.

By methodically marking your results in your research log as you go, you create a clear account of what’s been done and what needs to be done next, because blanks in your Results column indicate work yet to be completed.

In some cases, your results will be inconclusive or incomplete. Maybe you ran out of time as a library was closing and had to stop midway through your review of a newspaper on microfilm. Or perhaps you only checked the index of a book and not the relevant chapters. If your search was online, maybe an index isn’t available and you’re having to slog through thousands of digital images in a collection of wills.

Making notes of your exact actions and stopping points will save you lots of time and help you better manage your next research visit.

Next Steps

In a recorded presentation on FamilySearch about the importance of research logs, genealogist G. David Dilts, AG® explains how crucial it is to document as you go, complete your research log, and to transfer this information to your family group sheet and other records immediately after you return from your trip or close down the search program.

“You need to do these things before you lay your head on the pillow,” he says. “I consider these things to be the essential part of the most important principle that I can think of in genealogy — that you organize as you go.”

If you’re keeping your main working family tree online, either in software or in a program like MyHeritage, Ancestry, or FamilySearch, part of your documentation process is adding these new positive findings to those records.

This is a simple step in most every program. In Ancestry, for example, you’d simply click the “Add Source” field on an ancestor’s profile page.

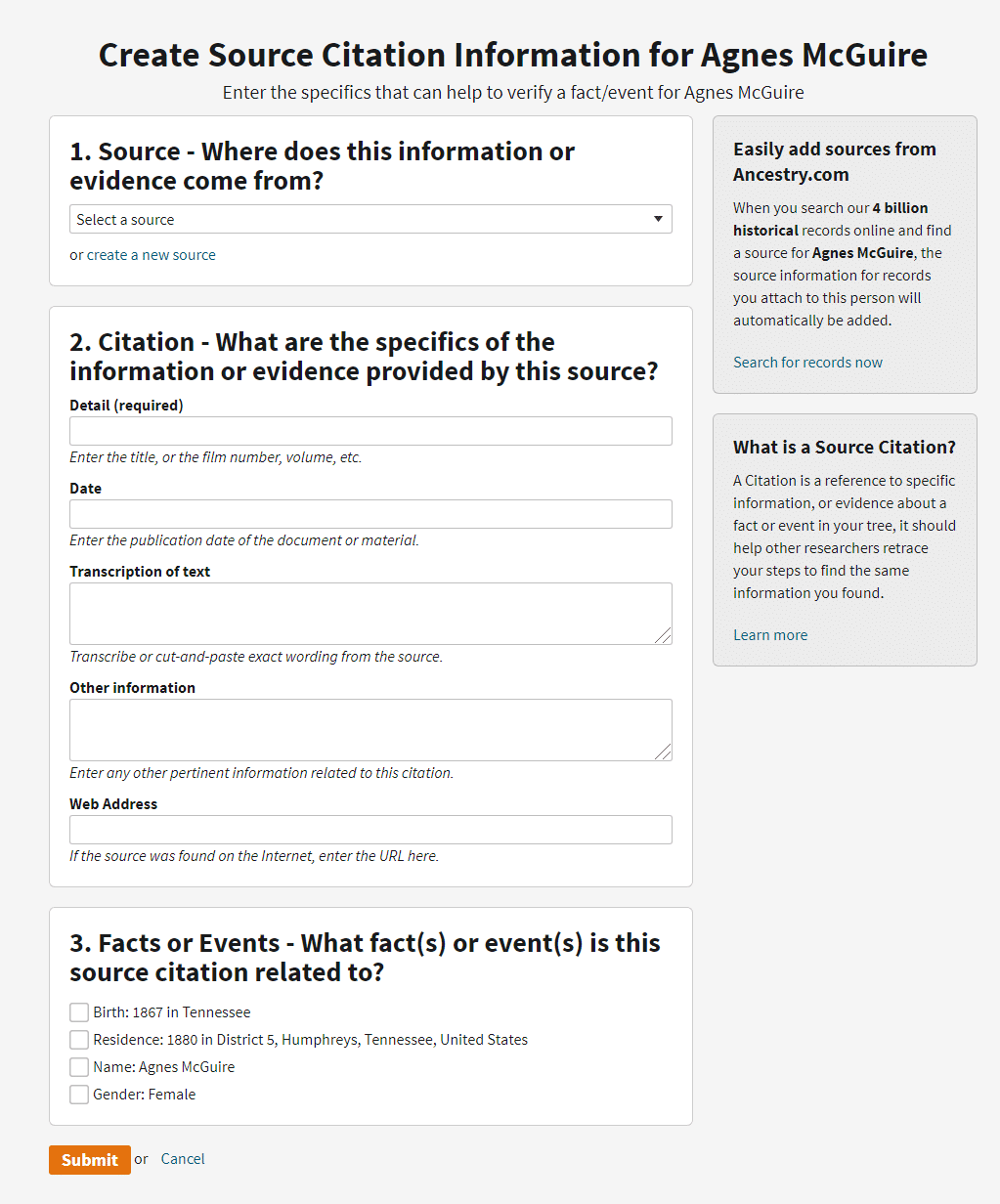

Next, you’d complete the form using Ancestry’s drop-downs and by filling in the blanks:

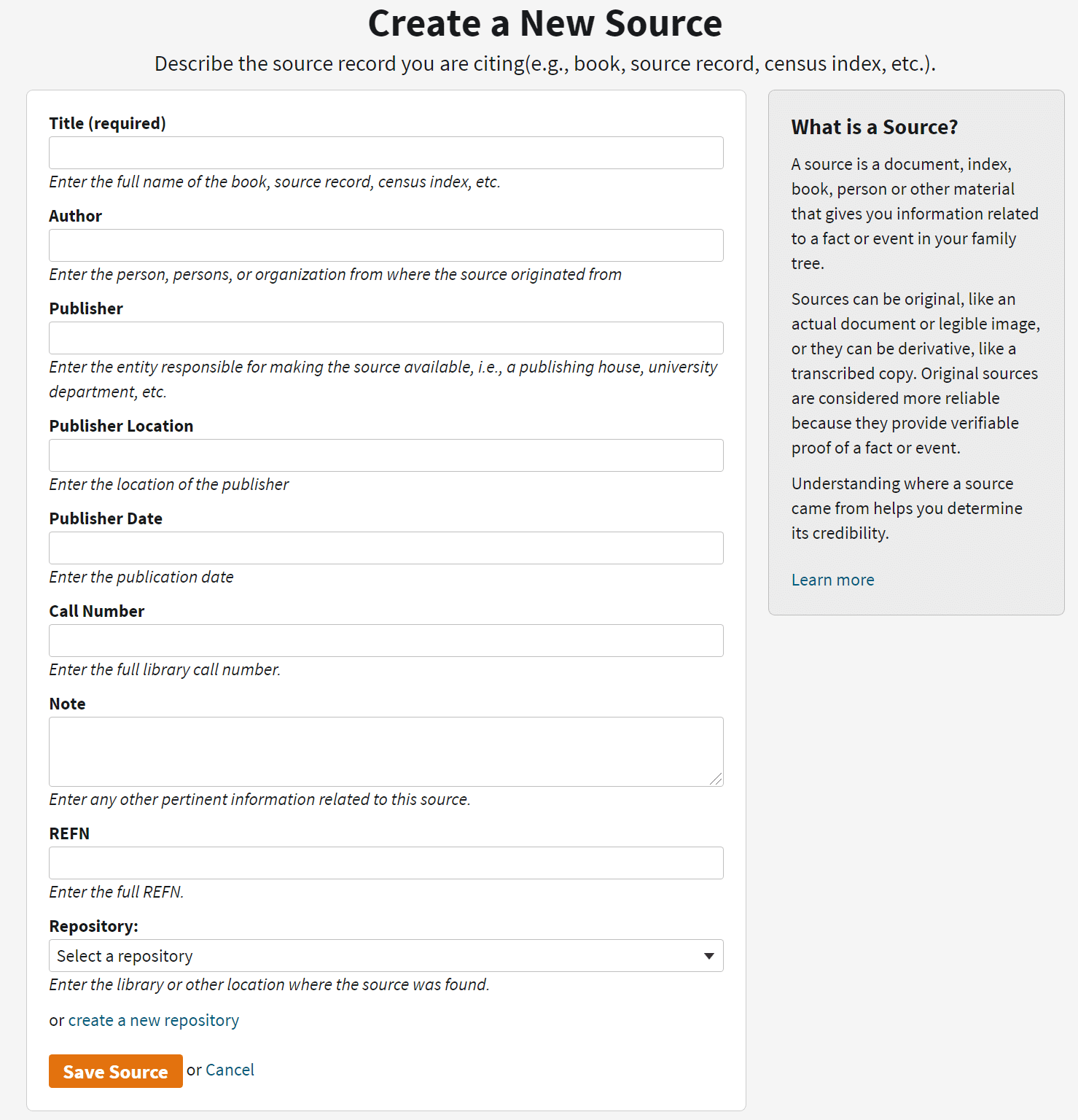

If your source is not listed in Ancestry’s drop-down menu, click “Create a New Source” to enter the citation information you recorded about the source on your research log. This creates a solid, easy-to-follow citation within your ancestor’s profile.

For more help with Ancestry, see our Ancestry Crash Course.

PRO-TIP: It’s worth repeating here: Don’t try to go back and create research logs for every family file or member during your process of organizing your genealogy collection. Instead, wait until you’ve worked through organizing your material into family files in the next lessons. When you’re at a stopping point, choose one or two family files as your research focus, and complete a family group sheet and research log(s) for your research going forward.

Adding to Your Research Log

It’s not only onsite or online research that you should enter into your research log. Any information you receive from a cousin by email, letter, or personal interview relating to a particular family group should be added to your research log and filed in your family group file. Every piece of information is a potential clue to your ancestor’s story.

When you add every search or bit of a clue to your research log the right way, and keep your personal organization system going, it’s incredibly rewarding to go back to the log the next time you search and see what all you’ve accomplished. The fillable version of the form we have provided allows you to make changes, or additions, right on your computer. You may also like to take advantage of the fillable Notes page as well for more details about your searches.

To complete a hands-on lesson that will help you get familiar with research logs and access the form sign up here.

This lesson about research logs is part of our online Organization for Family Historians course. To access the entire 36 lesson course, associated hands-on activities and quizzes, and digital workbook (which includes a fillable research log) check out our Course Center.

I am on a fixed income and cannot afford your courses, but want to thank you for the help you have provided me in organizing and learning how to create a meaningful research log after over 40 years of research. You are a godsend.

I would love to do your online courses, but I’m on a fix income and I put back money every week just to pay every six months for my ancestry account. ty for all your free information you give me.

I was directed to your website and this article by the New York Jewish Genealogical Society’s Winter 2022 edition of their journal, Dorot. This is wonderful. I feel like saying, ” where have been all of my life!” The truth is that after starting on my family’s genealogy in 2009, it is really only in the past year that I have come to understand the purpose and need for a “research journal.” I have asked a number of people in a number of places as to how to go about doing this, but have never received a reply. For the past two “lock down” years I have taken a break from actually working on the tree, but have zoomed in on many programs and have done a lot of history reading. I am ready to dig in again and am very excited about your helping me on the right path. Thank you! Thank you!