“What is a suffix in a name?” It’s one of the genealogical mysteries no one really talks about: What to make of those pesky letters and abbreviations that randomly appear after a person’s name in old documents and records.

These letters, commonly and collectively called a suffix or name suffix, can provide game-changing clues as to our ancestor’s identities, relationships, and accomplishments — no matter how random they may seem. Let’s take a closer look.

What is a suffix in a name, and how do they work?

In general terms, a suffix is one kind of affix (something that is added to the end of a word). This encompasses endings of verbs like -ing or -ed, which change the tense, and endings like -ism and -ship, which change a noun’s meaning.

Genealogists may also be familiar with a name suffix like -son which in ancient days was added to a father’s name (patriarch), creating a new surname (e.g. Jacobson) which showed kinship (“son of Jacob”). We explain how this works in our article about understanding surnames.

For our purposes, though, we’re interested in another way they are uses: When an abbreviation, an acronym, or other word or notation is added to the end of a person’s full name to apply some sort of meaning. Understanding these letter and number combinations can help us better understand our ancestors in a variety of fascinating ways.

How generational suffixes like Sr, Jr and III work

The most common examples American family historians will recognize are those indicating generational relationships, like Jr and Sr.

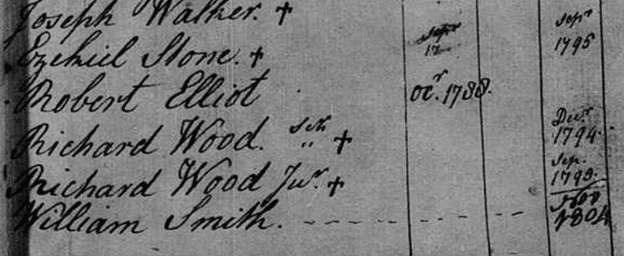

These are usually included as Senior, Sr or Sr. for a father – Junior, Jr or Jr. for a son – or the roman numerals II, III, or IV for generations that follow. These are called patronymic or generational suffixes, and are traditionally used when a male is given the exact full name of his father.

In that case, Sr. or I will be added to the father’s name, while the son will be given a Jr. or II. When a name is carried on to a third and fourth generation, most families switch to the numerical use of III and IV. When a family is the first to start assigning these suffixes the father will not show a Sr. on records until he has fathered the son who will become Jr.

Naturally, having three or four males with the same exact first, middle, and last names can be troublesome, especially in modern times, where longer life spans mean multiple generations are co-existing. For this reason, the younger generations sometimes adopt nicknames that indicate their place in the generational line-up, like “Trey” or “Tripp” if they are a III, or “Quaid” or “Cort” for the fourth in the namesake line.

Some people get pretty creative with their generational nicknames; for example, NFL quarterback Patrick Lavon Mahomes II, son of baseball great Patrick Lavon Mahomes, Sr., recently named his son Patrick Lavon Mahomes III, but calls him “Bronze” to indicate that he comes in “third place” in the line.

Important exceptions to the rule

As with most “rules” of genealogy, there are exceptions to the Jr. and Sr. or I, II, III naming conventions. For example, a researcher cannot just assume that two individuals with the same full name and Sr. and Jr. are father and son. In some communities, two men with the same name who were unrelated or distantly related were given Sr. or Jr. only to help the townspeople tell them apart in documents (“Sr.” being the older of the two).

Sometimes, a son will be given Jr. informally even if he doesn’t share the exact name as his father — perhaps they have slightly different middle names. A well-known example occurred with Francis Albert Sinatra and his son Francis Wayne Sinatra, who was sometimes called “Jr.”

Another anomaly occurs when a Sr. dies; in some cases, his same-named son, formerly a Jr., will drop the Jr. from his formal name. In other cases, the son will assume Sr.; this is especially common when there is a third generation with the same name.

Lastly, males who are named after a relative who is not their father (e.g. an uncle, a grandfather, or even a deceased sibling) can also use a naming suffix; however, they typically choose the numerical form of II (“the second”), rather than Jr.

The British royal family uses this naming convention. For example, we know that the father of King Charles III was Prince Philip, and was not named Charles; rather, King Charles III is the third monarch to use the name Charles. This can certainly make the order of the British empire confusing, but can appear in genealogical records of common people as well so it is important to understand.

Did women ever use Sr or Jr?

Occasionally, women who were given the exact name as their mother would add a Jr. to their name, but that naming convention is uncommon — perhaps because women would eventually change their surname (also known as family name) to that of their husband.

Take, for example, the family of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his wife, Anna Eleanor Roosevelt. The couple gave their third son their father’s name, dubbing him Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Jr. They also gave their only daughter her mother’s name, Anna Eleanor Roosevelt, and historians often refer to the daughter as a Jr.

What are post-nominal letters?

To further muddy the water, it’s important to understand that the generational options discussed earlier aren’t the only ones you’ll come across in your genealogy pursuits. The majority have nothing to do with familial relationships, but they can be just as informative. Collectively, these letters are called post-nominals, and may indicate academic degrees, social standing, professional titles, accomplishments or affiliation, and even religious associations.

Here’s a fun one.

What the heck does esquire really mean?

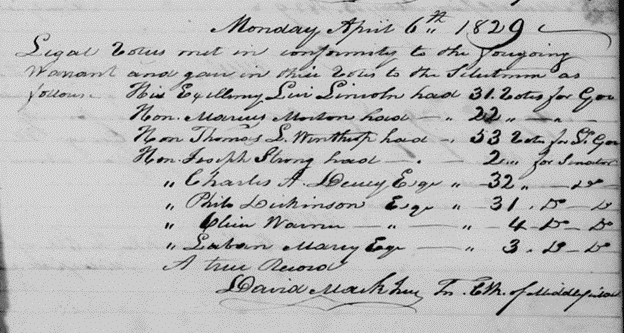

It’s not at all uncommon to see the word “Esquire” or the abbreviation “Esq.” following male names in early American documents, like the 1829 listing below.

Today, “Esquire” is most often used by the legal community as a title of courtesy for attorneys, or its abbreviation “Esq.” after their surname, mostly in formal correspondence. However, in England, it is not used professionally, but was once an honorific for principal parish landowners, holders of knights’ estates who hadn’t taken up their knighthood, eldest sons of younger sons of peers, eldest sons of baronets and knights, and some officials.

The English honorific has mostly fallen out of fashion, but until the early 19th century, it held a place in American social society. Generally, a man’s name might be followed by Esq. if he held a local office, was a member of a fraternal organization, was wealthy or a business owner, or was simply considered of high social standing.

In fact, at one time in the late 1700s, many people complained that it was being overused, and was given to any male who did not already have a different one. Therefore, it’s probably best not to assume that your ancestor with Esq. held a certain position or role, when it could stand for so many different honors.

The meaning of academic post-nominals such as BA, MBA or PhD

An academic suffix would be used to indicate a degree which the person earned at a college or university, and usually indicate the particular area of study in which the degree was achieved.

For example, BA stands for Bachelor of Arts, BS for Bachelor of Science – indicating different types of Bachelor’s degrees, etc. Master’s degrees follow the same suit (MA for Master of Arts, MBA for Master of Business Administration, etc.), as do academic and professional doctorates, including JD for Juris Doctorate (law degree) and PhD for Doctor of Philosophy.

Individuals holding advanced degrees are also entitled to use other options, such as Esq. for an attorney who has earned a Juris Doctorate, or the name prefix Dr. for someone who has their PhD. Traditionally, though, they will use one or the other notation (Dr. John Smith or John Smith, PhD), but not both (Dr. John Smith, PhD).

Although it is used today in the USA primarily as an honorary degree, the Doctor of Laws degree, which uses LLD, was a popular doctorate-level option in legal studies in early American universities. It is still awarded by schools in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and a number of European countries.

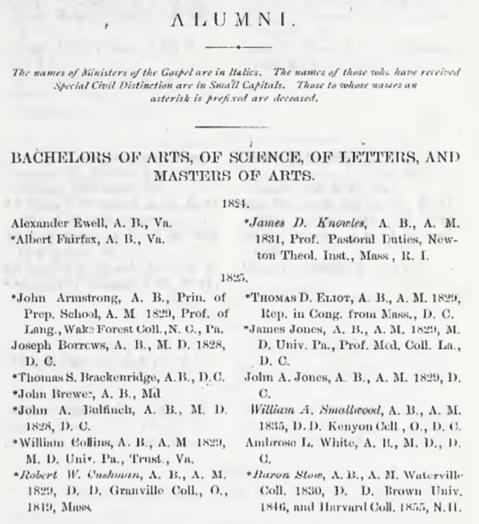

It’s also interesting to note that in some early documents, such as the Catalog of Officers and Graduates of Columbian University above, the suffixes for bachelor’s and master’s degrees were written in reverse of what we use today. For example, a Master’s of Art was abbreviated as AM, while a Bachelor’s of Art was AB, an acronym for the Latin phrase artium baccalaureus.

Making sense of religious suffixes

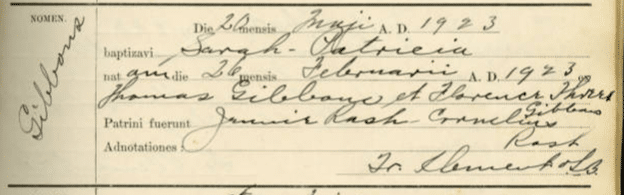

Another version you might come across during your genealogical research are religious ones. These letters, which are mostly acronyms, represent the religious order or institute to which a person belonged. They are especially prominent in the Catholic Church, as priests, nuns, monks, and other members of the clergy will typically use their particular religious suffix in their formal signature.

In the example below, the priest’s signature, “Fr. Clement OSB,” in this 1923 baptismal register indicates that Father Clement was a member of the Order of Saint Benedict, a monastic religious order of the Catholic Church. There are hundreds of different orders and institutes in the Catholic Church alone, and therefore hundreds of various post-nominals.

Clergy from other religions also used suffixes. For example, VDM (Verbi Dei minister or verbi divini minister) was often used by ministers or pastors within Lutheran and Reformed churches. Likewise, clergy from multiple religious used MG to denote their role as a Minister of the Gospel.

Post-nominals for theological degrees are also commonly found in genealogical records. DD, for example, indicates a Doctorate in Divinity, while MTh is used for a Master’s in Theology.

Professional and military suffixes

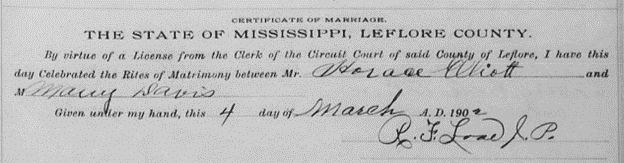

If you’ve studied any United States marriage records, you’re bound to have come across “JP.” Most family historians quickly learn that this is an acronym for Justice of the Peace, a judicial official who presides over a variety of court proceedings.

However, you’ll most often find JP after the name of the official who performed your ancestors’ weddings, if they were not married by a member of the clergy. In the example below, the marriage record of Horace Elliott and Mary Davis was performed by Justice of the Peace R.F. Love.

Military post-nominals are common as well. For example, USN is often included in the signature of a person in the U.S. Navy, while CSA was the option used by individuals fighting for the Confederate States of America during the Civil War.

In addition to a particular profession, professional inclusions often indicate a certification or membership in an organization. Members of the Daughters of the American Revolution may add DAR to their names, while Sons of Confederate Veterans may use the SCV.

Today, professional affiliation or credential options exist for practically every type of industry or area of expertise, from accounting to veterinary medicine. For example, PHR after a name means a person has completed the requirements to become a Professional in Human Resources, while CRT means they are a Certified Respiratory Therapist. Of course, most of the professional choices used today came about in the 20th century, so running across these within your genealogical studies prior to the early 1900s will be rare.

What about Mr. and Mrs.? The difference between a prefix and a suffix

Common titles, sometimes called name prefixes, include Mr., Mrs., Miss, and Dr., as well as military designations, like Col. for Colonel, Sgt. for Sergeant, Pvt. for Private, etc. and come before a given name. These are not suffixes.

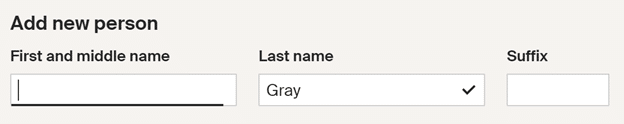

While we haven’t covered every possible variation you might discover in old records and documents, you can probably gather that they, whether denoting an academic, social, religious, or professional status or a generational continuance, are quite commonplace. Therefore, most genealogical software includes a “Suffix” field where you can add the appropriate designation (as seen in the “Add New Person” forms from Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org below).

You’ll notice that the second example above from FamilySearch.org includes a field for Title and is where prefixes, as explained above, should be included.

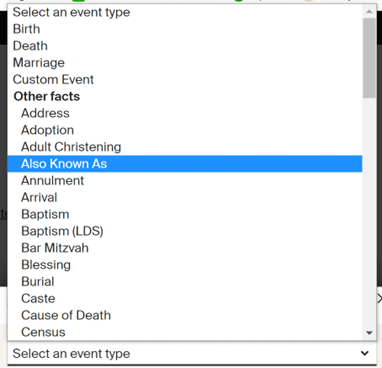

Some family history researchers will use the Suffix field for other purposes, like nicknames or personal notes, which can be frustrating and confusing if the tree is online and public. Most genealogical software and online programs include fields for nicknames, notes, and other designations, such as Ancestry’s “Also Known As” fact field, shown below. For uniformity, it’s best to always use the fields provided in the system for the information they actually represent, or create a Custom Event or fact for your particular details.

How to include a suffix in a name

Figuring out how to include a suffix can be confusing. As mentioned, when including this information in your family tree, always place it in the designated box. When writing it out, you can use the standard format seen below.

In the past, a comma was used to separate the suffix from the surname and this is still a proper way to do so, but is less common today. Note that when surnames are listed before given names a comma is still used.

Examples of suffix use:

- Single suffix: Andrew Jones West, Jr.

- Multiple suffixes: Andrew Jones West, Jr., PhD

- Last Name First: West, Andrew Jones, Jr., PhD

In the past you may also have seen a married woman using her husband’s name along with one of more suffixes – such as Mrs. Andrew Jones West, Jr.

If your ancestor has attained multiple additions to their name, etiquette dictates that they be listed in a preferred order.

Here is the proper order for adding suffixes:

- Generational

- Religious orders

- Theological degrees

- Academic degrees, arts before professions

- Honorary degrees, honors, decorations

- Professional licenses

- Professional certifications

- Professional associations & affiliations

Why this research is important to your family tree

Finding a suffix associated with an ancestor’s name can provide all sorts of clues for the family historian, whether it’s a “II” that provides a lead to a close family friend or relative who was honored as a namesake or a professional one that indicates their occupation or religious affiliation.

The key to puzzling these letter and number combinations out is to put them into context, considering the type of document on which it appears (court records, church documents, military files, etc.) and performing thorough research on the exact meaning.

As a family historian, it’s important to look at these with a certain degree of skepticism, and not simply assume that the Sr. (father) and a Jr. or II held the same name. The only way to confirm these relationships is to perform exhaustive research.

Also keep in mind that the situations we’ve discussed here are typical uses in western culture in the English language, but varying countries and cultures have different traditions when it comes to naming their offspring or assigning post-nominals.

And when searching for ancestors with a name suffix, please remember that they were not always included in documents or may have been included in various forms. You may see, for instance, Jr., Jr, J, II or junior for a son – or the record keeper may have skipped it altogether. Generally it is best to search for names and to use the dates of birth and other relationships (such as spouse or children) to ensure you have the correct generation.

Additional information to help making sense of names can be found in our online courses or in our other helpful guides. See this section of our site.

Also read: Finding the Hidden Clues in First Names: A Starter Guide

By Patricia Hartley. Patricia has been researching family history for over 30 years and has an M.A. in Public Relations/Mass Communications from Kent State University.

thank you for this info, I really needed it! now maybe I can break down my brick wall, I have been following the wrong names due to exactly what you mentioned!

Military Awards are also very important. examples “VC” Victoria Cross the Highest award for Valour. or for the USA the C M of H.