Have you ever wondered about elections of the past and how they influenced our ancestors’ lives? What issues were important to the men and women in our family trees? What challenges did they face when it came to exercising their right to vote? And in the case of minorities, women, immigrants and many others, what was it was like to have that right be limited or completely denied?

One way for us to explore this interesting topic is by looking back at the records these voters left behind — and Voting Registers offer an exciting way to do that. Voting Registers are lists of those people in a geographic location that were eligible to vote, and many of them are available to family historians in some form or another.

What information can I find about my ancestors in Voting Registers?

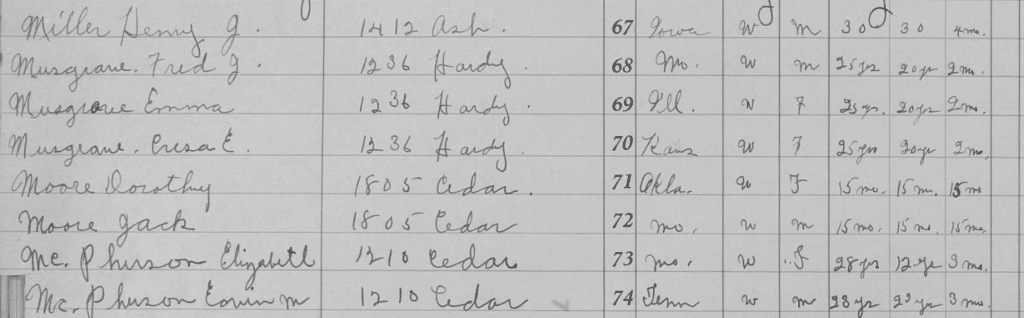

Turns out, quite a bit. Many registers read like a census — with full names, ages, addresses, locations of birth and even occupations recorded. The most interesting ones include all of these details and more — whereas some simpler versions may contain fewer facts. Because these registers were often laid out alphabetically, members of the same household are usually listed together. This gives us an opportunity to explore family relationships as well.

Of course, these records are also limited. Generally, registers are only available after the mid 1800s and often not until the late nineteenth or early 20th centuries. And because many groups of people were excluded from voting at various points in American history, a good deal of people are simply not included.

Still, this often overlooked record can become an important addition to your family tree — helping you add fascinating new information to your files.

How can I locate Voting Registers for genealogical use?

Unfortunately, these records are harder to find online than many other collections, but they are available. FamilySearch, Ancestry and MyHeritage all carry them, as well as some smaller family history research sites. Your best bet if you want to look for these collections specifically is to visit the card catalogs of the large sites and see what’s available. You can find more help with that here, or in our online courses.

Here is one such browsable collection from FamilySearch covering Jackson County Missouri (1928-1955)- a good deal of information is recorded for those lucky enough to have ancestors from this area. The following record section comes from this collection.

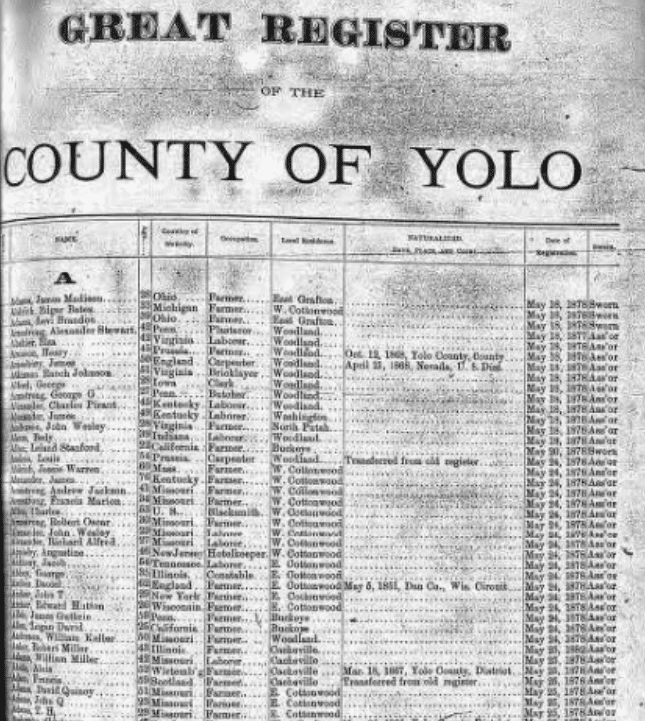

Here is another example record from one of the early 20th century California voter registers found on Ancestry.

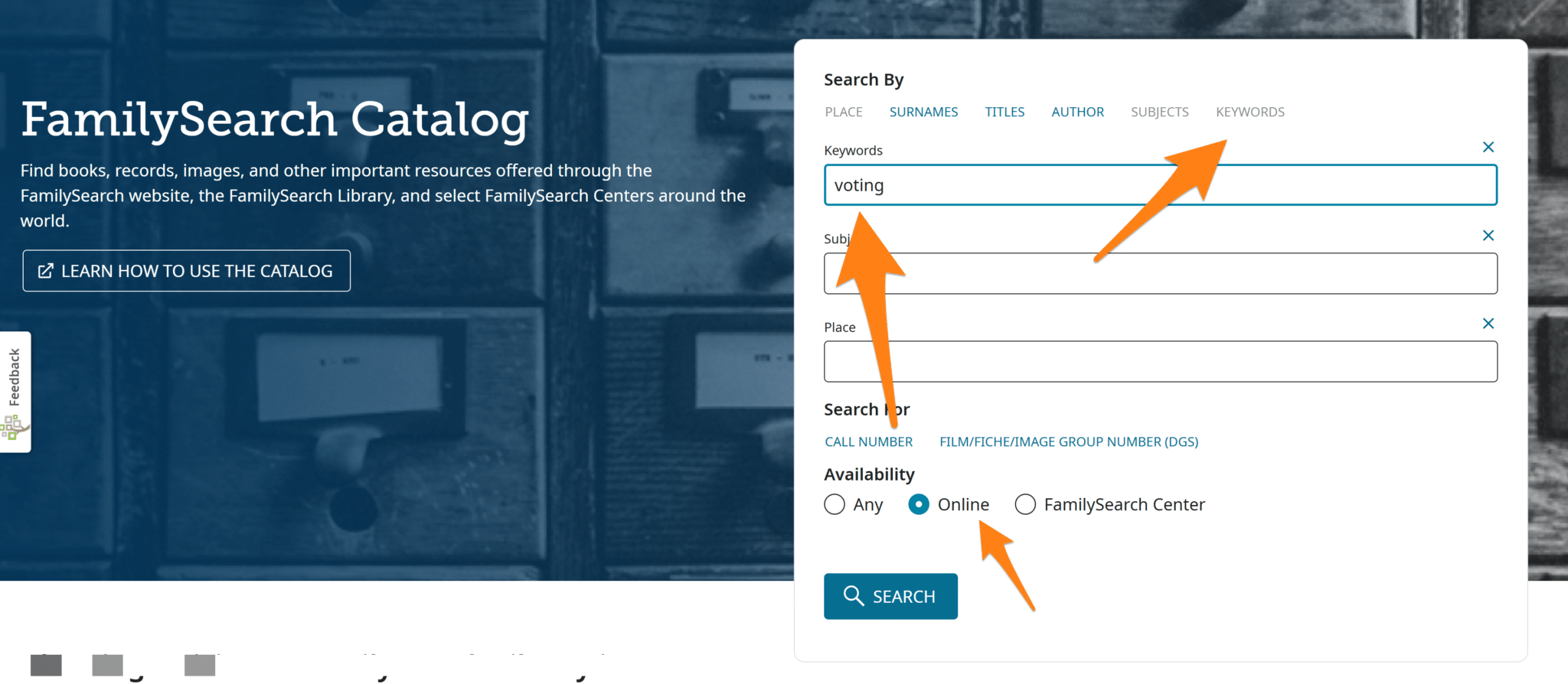

To locate more voter registers for free you’ll have to do some digging. FamilySearch is the best place to find these records if you don’t have access to a paid subscription to Ancestry. When searching their catalog, be sure to choose “online” as the location and use the keyword option to looking for the keyword “voting” or “voter” as a start. You can add a place name to further refine your results.

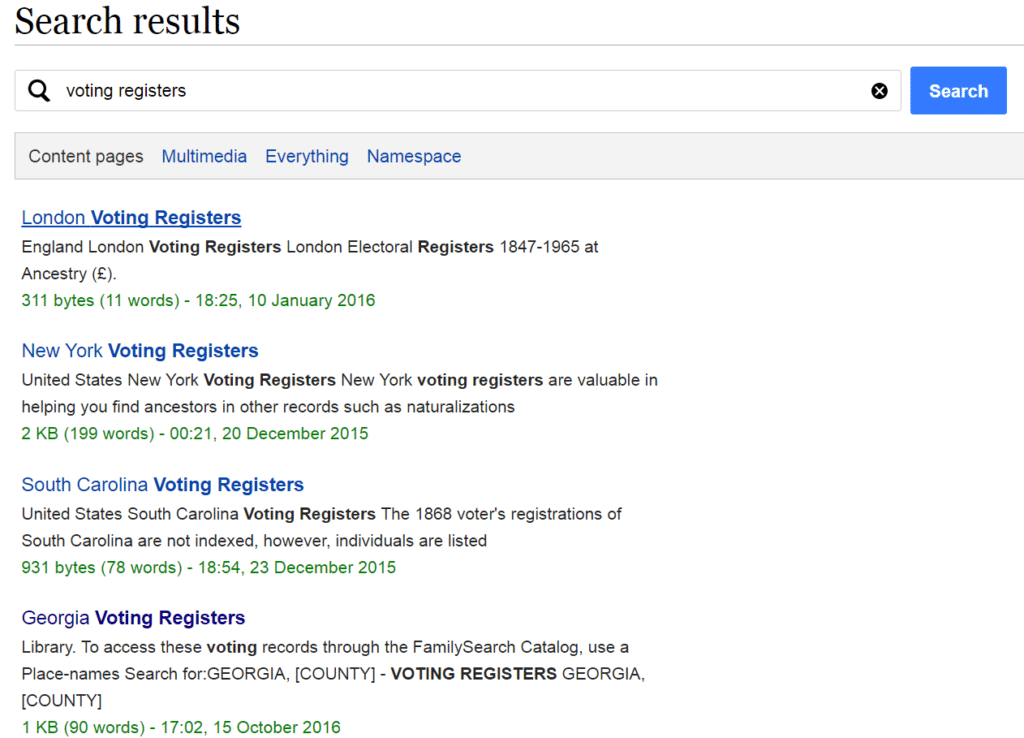

Another excellent way to locate voting registers anywhere online is to visit the research wikis on FamilySearch. A search for “voting registers” will bring up helpful pages about what records were created, and where you can find them online and off. Add in your specific location of interest for more specific results.

Registers for some locations can be found online for free through sites like RootsWeb and local historical and genealogical societies and libraries may also make these collections available or can tell you where to find them. Use your favorite search engine to search for these records in your area to refine your results and find what you need. Our online course, Google for Genealogy, offers a great deal of help for using Google to find the records you need online.

Although you may need to put some extra effort into locating these somewhat elusive records, Voting Registers are not to be missed and may provide exciting new details about your ancestors.

Featured Image: “The County Election” by George Caleb Bingham

Article by Melanie Mayo, Family History Daily Editor

Another source is to seek voting rolls in territories that voted for full statehood.

In England, voting in the 17th and 18th centuries was often a public affair- no such thing as a secret ballot, and in some cases the voters and how they voted were published in books. So, if your English ancestor was a householder it might be worth seeing if such a book exists. I managed to find one from Yorkshire with an ancestor in it, who voted for his landlord surprise surprise!