Have you ever met a genealogist who didn’t love visiting cemeteries? They’re right up there on most family historian’s lists of favorite haunts – alongside libraries, courthouses, and archives. We love visiting historic places that provide clues to the mysteries of our ancestors’ lives. Cemeteries are full of history and, of course, mystery, including the fascinating clues and hidden messages in grave marker symbols that are just waiting to be deciphered.

A grave marker was often a family’s final — and sometimes only — option for memorializing their deceased loved ones. Official vital records that recorded birth and death dates have only been required in the US since the early 20th century, and as genealogists well know, other sources of data on a person’s life can be quite scarce, or even nonexistent.

A marker (often made of stone but sometimes other materials, such as wood, metal or clay and referred to as a gravestone, tombstone or headstone) is one record that can potentially preserve names, birth dates, and death dates for centuries and for future generations to discover. And if we’re lucky, our ancestors’ families added more clues to how their loved ones lived in what they chose to include, in addition to names an dates, on a marker. While sometimes thought of as only decorations, specific symbols held very special meaning to the people who chose them.

While it’s impossible to document the meaning of every symbol found on graves, most denote a person’s religious beliefs, hobbies, social associations, cultural or ethnic backgrounds, civic or fraternal affiliations, lifelong trade, commercial dealings, political beliefs, professional career, or military services.

Common symbols found on grave markers

Although most symbols can be traced back to a person’s endeavors, personality, or beliefs, some aren’t indicative of were quite common only during certain eras, while others have endured and are still used today. But what do these commonly-found images mean?

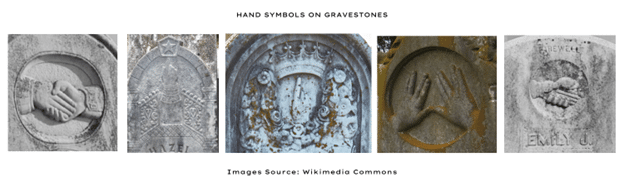

Hands and fingers on a gravestone

Hands and fingers have been included in gravestone engravings for centuries, and some forms are still popular today. You might find the following while looking for cemetery symbols:

One Hand on a Grave Marker: Often, meant to depict the hand of God

Praying Hands: Usually associated with religious prayer, but could also symbolize obedience, submission, sincerity, repentance, or veneration one’s higher power

Clasped Hands/Handshake: Friendship; farewell to earthly life and welcome to heavenly life; or reunion in heaven.

Forefinger Pointing Up: Hope for heaven or a soul’s passage to heaven.

Forefinger Pointing Down: God reaching down for the deceased’s soul.

See the images below for examples.

Animal images or sculptures on gravestones

Engravings or actual sculptures of animals are often included in gravestones for particular reasons. For example:

Lions: May indicate strength, courage, or bravery of the deceased or may be meant to protect the grave.

Snakes and Serpents: Historically symbols of everlasting life; a snake formed into a circle indicates eternity (and, incidentally, is called an ouroboro).

Horse: Symbolizes courage and generosity.

Eagle: Stands for courage, strength, and immortality, but could also indicate patriotism.

Dragonfly: A symbol of change, transition, lightness, or joy.

Frog: Depicts worldly treasures or resurrection.

Butterfly: Symbolizes rebirth, resurrection, or the natural cycle of life and death.

Dove: Indicates peace, or the deceased at peace.

Lamb: Often seen on the grave’s of children, symbolizes innocence and purity

Other commons gravestone symbols

Some common gravestone symbols are closely related to mortality and death, while some are representative of a person’s livelihood.

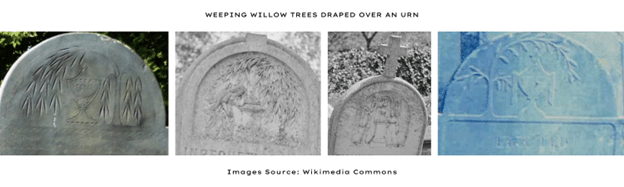

Urn Covered in Drapes: Urns are the traditional receptacles for cremated remains, and urns on gravestones are quite common. An urn covered with a drape or fabric can represent multiple things: death’s “final curtain,” a cloth to protect or guard the ashes, or that the soul has departed the shrouded body for heaven.

Inverted Torches: While a “right-side-up” burning torch often represents immortality or everlasting life, an upside-down torch indicates the flame of life has been extinguished.

Broken Column: Any broken or incomplete monument or engraving — a column, sword, tree, flower, branch, or tree stump — typically indicates a life cut short.

Rising or Setting Sun: Often indistinguishable, the rising or setting sun symbolizes an earthly life coming to an end and resurrection into the next life.

Keys, Arches, or Gates: Either of these can symbolize entrance into heaven, or the transition from earthly life to the afterlife.

Books: If not representative of the Christian Bible or other religious text, books may indicate the deceased was a teacher or scholar.

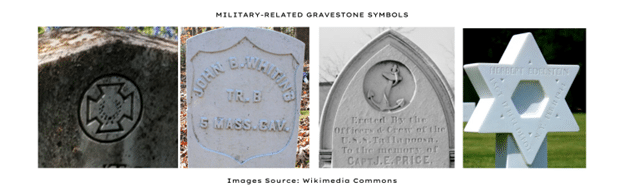

Military Insignia: Most symbols of the current Armed Forces are easily recognizable, but you might find other symbols on older gravestones that indicate military service, including:

- Southern Cross of Honor (for Confederates who fought in the Civil War)

- Raised Lettering Inside a “Sunken Shield” (for those who fought for the Union)

- Anchor (for sailors)

Religious gravestone symbols

Throughout the centuries, a person’s religious affiliation or personal beliefs have been such an important and integral part of their lives that symbols of their faith are quite often incorporated into their gravestones.

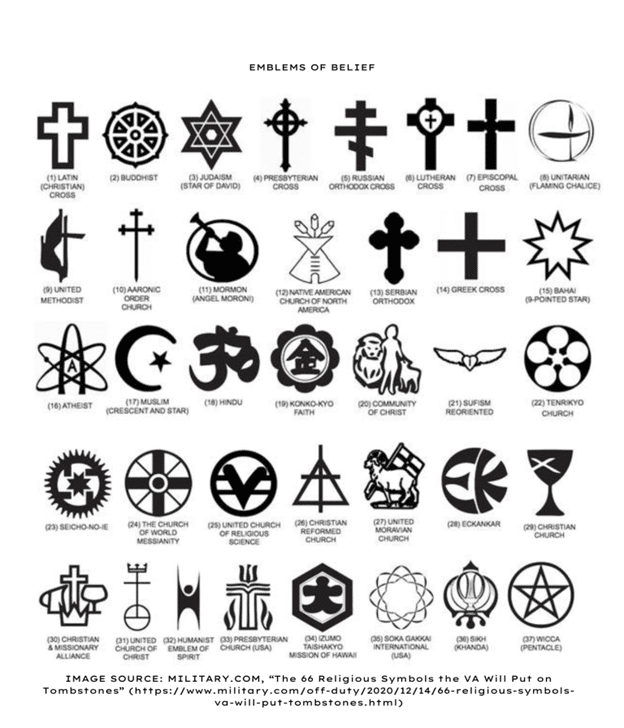

Recognized emblems of belief

Called “emblems of belief” by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) in its Government Headstones and Markers reference document, symbols that represent a person’s religious faith are still in use today on both military headstones and other grave markers. You might find similar emblems on the non-military and historical graves to indicate a specific faith.

Here are 66 religious symbols the VA will add to gravestones:

While the VA’s emblems of belief reflect the current symbols that signifying a person’s religion or belief system, you may find variations or older representations on your ancestors’ gravestones.

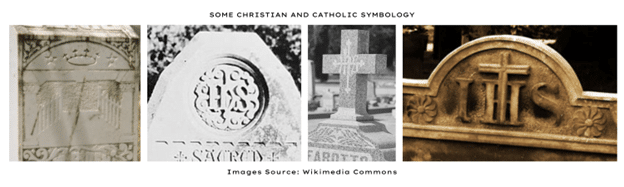

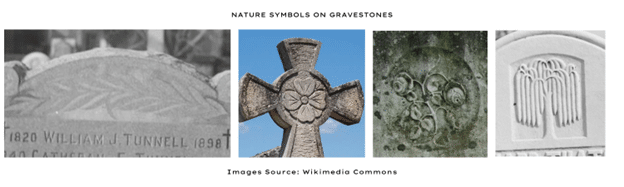

Christian symbols

In addition to the above, you might find some of the following symbols on the gravestones of those of Catholic and other Christian faiths:

Alpha and Omega: The Greek letters Alpha and Omega are the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet. On gravestones, the letter A and the lower case ώ or upper case Ω symbol represent Jesus.

Chi Rho or Chrismon: Chi and Rho are the first two letters (ΧΡ) of “Christ” in Greek ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ. (Christos). The symbol for Chi Rho is the letter P intersected by the letter X.

IHS: Early Christians shortened Jesus’ name by writing the first three letters of his name in Greek, ΙΗΣ (from his full name ΙΗΣΟΥΣ). Because the Greek letter Σ (sigma) is written as an S in the Latin alphabet, the gravestone symbol will be read as ΙΗS.

INRI: These initials stand for the Latin phrase “Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum” or “Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews” — the inscription placed over Christ’s head during the Crucifixion.

Anchor or Cross and Anchor: Because hope was associated with salvation, Christians often use the anchor on gravestones to symbolize the hope that the deceased was “anchored” in heaven.

Celtic Cross: While a cross represents the Christian faith, the ornate celtic cross is common in cemeteries across Scotland, Ireland and Wales and may be engraved on the gravestones of people of Scottish, Irish, or Welsh descent in the US.

Bible: May represent a religious lay person.

Triangle: This symbol could be used to represent the trinity of the Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit. If there is an eye in the center of the triangle, it represents the all-seeing, all-knowing God.

Winged Wheel: May represent the Holy Spirit.

Vines: Evergreen vines may symbolize the Church and its followers, while vines with three-sided leaves may represent the Holy Trinity.

Shells: Scallop-shaped shells and clam shells may be a symbol of a person’s baptism in the church or their Christian journey through life.

Jewish gravestone symbols

While the six-pointed Star of David, which represents divine protection, is the traditional symbol found on the gravestone of a person of Jewish faith, other engravings also indicate Jewish beliefs.

Animals: Animals are closely tied with Jewish naming traditions; thus, the image of a certain animal on a Jewish gravestone may provide clues to a nickname or simply serve as a visual representation of a given name.

- Lion: Judah, Lieb, Levi, Aryeh,, Loew, or Loeb.

- Deer: Tzvi, Hersh, or Hirsch

- Bear: Dov Ber (a common compound name)

- Wolf: Zev, Ze’ev, Wolf, or Vulf

- Bird: Zipporah, Fayge, or Feige

Five Books: A stack of five books on a gravestone means the deceased was a student or scholar of the Torah.

Menorah: The traditional candelabra of the Jewish faith, the menorah on gravestones may represent pious or religious Jewish women.

Islamic (Muslim) grave markers

Crescent Moon: A common symbol of Islamic faith

Mosque-shaped Marker: Can symbolize piety

Please see this article for a look at historical Islamic markers.

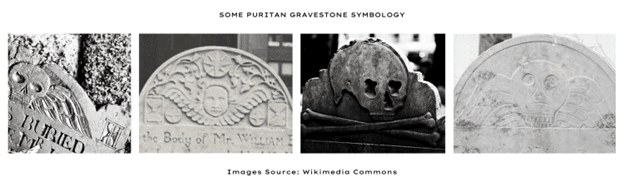

Puritan grave marker engravings

Some of the oldest gravestones in the New England area of the United States and beyond include symbols reflecting the beliefs of the Puritan faith. Although Puritanism is not widely practiced today, the symbolism used in Puritan times can sometimes be found on gravestones in more modern cemeteries.

Winged Skull: This represents the flight the soul takes after death. According to one source, the wealthier 16th century Puritans would have a skull or skull and crossbones carved on their headstone as “a bleak reminder of their belief that only the elect would go to heaven while the majority would be but bones in the ground.”

Coffin, Skull and Crossbones, or Shovel and Pickaxe: All three are symbols that simply reflect human mortality.

Hourglass: Reflects the passage of time

Winged Hourglass: A literal interpretation of the saying, “Time flies,” often indicating a short life. Carvings of Father Time or the Grim Reaper are often found along with this symbol.

Scythe: Images of the personification of Death typically include a scythe, as Death is making the “last harvest”

Skeleton or Skull: Both are anatomical personifications of death

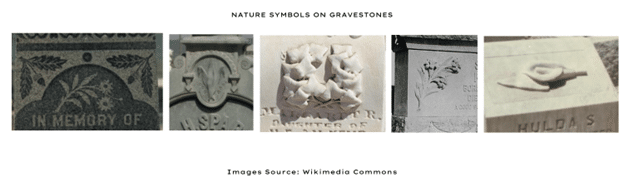

Nature-related gravestone engravings

Cemeteries are often known for their lush landscaping: Flowers, trees, and manicured lawns contribute to the sense of peace to be found among the dead. However, many of these nature-related symbols are also found on gravestones, and may have significant meanings.

Trees: A tree of indistinguishable species often indicates the “tree of life,” a symbol that means longevity in many cultures. Specific types of trees hold other meanings:

- Olive Branch, Tree, or Leaf: Peace, good intentions, longevity, fertility, or prosperity.

- Weeping Willow Tree and Urn: Grief and immortality.

- Evergreen Tree: Remembrance and faithfulness.

- Oak: Strength, strong faith, manliness, honor, or steadfastness.

- Dogwood: Christianity, divine sacrifice, resurrection.

Bouquet of Flowers: Like those placed on a grave to acknowledge the deceased, a bouquet of flowers inscribed on the stone offers condolences to the family. In the 19th century, a bundle of flowers was also an indication of love. Specific types of flowers hold other meanings:

- Lotus Flower, Water Lily, or Lily of the Valley: Rebirth and reawakening.

- Lily: Purity, love, innocence and goodness.

- Morning Glory: Youth and love.

- Poppy: Death or eternal sleep.

- Rose: True love or romantic love, or, depending on the image of the bloom itself (a bud, half bloomed, broken) may symbolize the death of a child or young person. Two intertwined roses may be found on the shared stone of a couple.

Fruit: An assortment of fruit engraved in a headstone may symbolize the plentiful abundance of the afterlife, while specific fruits may have their own meanings:

- Pineapples: Hospitality, prosperity, or eternal life.

- Pomegranates: Nourishment of the soul.

- Grapes: Blood of Christ, God’s care, or the Last Supper

- Grapes with Leaves: Christian faith.

- Four-Leaf Clover: May represent Irish ancestry or membership in the 4-H Club, an American youth organization.

Corn: Corn could mean that the deceased was a farmer.

Wheat: A sheaf of wheat may symbolize the “end of the harvest” for a mature man who led a long, productive life.

Fern: Images of ferns may indicate humility, sincerity, and solitude.

Ivy: This evergreen creeping vine, when found on a gravestone, represents immortality, friendship, or everlasting life.

Wreath or Garland: Forming a vine, flowers, or greenery into a circle typically symbolizes victory, distinction, or eternal life. A laurel wreath, specifically, may be found on the gravestone of someone who excelled in athletics, arts, or literature.

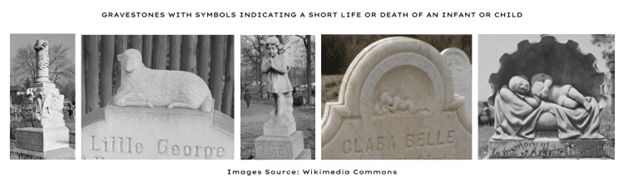

Symbols often engraved on gravestones of infants or children

Some of the most heartbreaking gravestones in any cemetery are those that are instantly recognized as belonging to a baby, child, or young person. While most of these symbols are quite common, you may not realize that others refer to a life that ended too soon. They include:

- Lambs (for innocence, the Lamb of God, or a child of God)

- Rosebuds (for a life that never bloomed)

- Adjoining Rosebuds (for a mother and child who died at the same time)

- Cherubs (to guide the child to heaven)

- Baby shoes, cradles, or chairs (empty or overturned because the child has passed away)

- Daisy (for the innocence of a child)

- Sleeping child (often used in Victorian era)

Initials sometimes found on gravestones

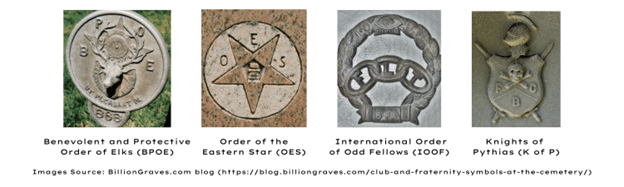

Sometimes cemetery explorers will find stones engraved with initials that don’t necessarily match those of the deceased. These acronyms often have religious meanings or reflect an affiliation with a particular organization.

RIP: Rest in Peace, from the original Latin “requiescat in pace.”

FLT: “Friendship, Love, Truth” are three degrees associated with the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, a fraternal organization first established in America in the early 1800s. A number with these initials may reflect the specific Odd Fellows lodge to which the deceased belonged. The initials are often accompanied by a three-link chain and an all-seeing eye, similar to the symbols of Freemasons.

FCL: “Fraternity, Charity, Loyalty,” which were the mottos of both the Daughters of Union Veterans of the Civil War and the Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic hereditary organizations.

K of C: Indicates membership in the Knights of Columbus, a global Catholic service organization founded in the 1880s.

FCB: “Friendship, Charity, Benevolence” are the values of the Knights of Pythias, a fraternal organization established in 1864 for governmental clerks.

BPOE: Shows membership in the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks fraternal organization, commonly known as the Elks.

Emblems of fraternal organizations

Although a deceased person’s affiliation with a fraternal organization can be reflected on a gravestone with initials, as described above, some also use the group’s official symbols.

Freemasons: Membership in a Masonic Lodge is most often indicated on a gravestone by the tools of the mason’s trade, including a compass, ruler, and a square. These tools are often accompanied by the letter “G” for God and geometry, stars, a sun, an all-seeing eye, or the letters ITNOTGAOTU, as seen in the last image below, which stands for “In The Name Of The Great Architect Of The Universe.” To learn more about Masonic symbols and beliefs, visit this Masonic Education website.

Independent Order of Odd Fellows: Affiliation with this fraternal organization is often represented on gravestones with some symbols similar to freemasonry’s, like the all-seeing eye. The symbol used most often is three chain links (which stand for friendship, love and truth).

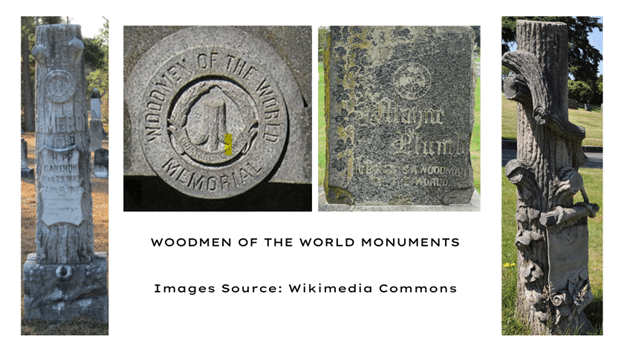

Woodmen of the World (WOW): Membership in this fraternal organization, which was founded in 1883 and is today is better known for its primary purpose as an insurance provider, often included a WOW-hosted burial ritual and the installment of a special WOW gravestone. Most Woodmen gravestones are easily identifiable in a cemetery as they are shaped like trees or sawed-off tree stumps, as shown in the image below. They may also include the Woodmen motto “Dum, Tacet Clamat” (or “Though Silent He Speaks”) somewhere along an edge or border.

Time to start deciphering

Stroll through any cemetery — modern, historical, or somewhere in between — and you’re sure to find gravestones with symbols just begging to be deciphered. Even if you’ve visited an ancestor’s grave dozens of times, recognizing and understanding the hidden messages in the symbols on their gravestone could open up a whole new facet into their lives!

I came across two grave stones each marked with a singular inverse capital letter N facing each other with no other markings. The cemetery goes back to Colonial days with several during the Revolutionary War period …any clues ti their meaning?

My grandfather has an emblem on his headstone that we would like to find out what it means. It’s a large E & at the top of the E is a B & at the bottom of the E is an L. I can provide a photo to help

Can you tell me when the term “Burried Here” (with 2 R’s) was used and when it ceased being used? Could you also speculate when the Bevel or Pillow type grave marker first came into use?

What do the initials “CA” before a name mean on a headstone?

Failed to copy and paste – turn of the century stone hammer on a pentagon on a star on a pentagon.

For possible identification, Is it possible to submit a photo of an unknown symbol?

Extremely interesting read. Thank you for the information. Gravestone markers in U.S. National Cemeteries with gold embossed letters are those of Medal of Honor recipients.G

You have forgot all the Headstones of the fallen HERO’s of the Armed Forces and Fire Services

Thank you for the information you have shared to all. It very comforting to many of us, who had no idea. I volunteer for Find A Grave listings. Wondered what they all meant to the family & deceased.

Ljw

And there are symbols for heritage-based organizations: DAR and Mayflower Society