U.S. Census records offer a unique look into the past and a chance to discover valuable details about your family’s history. Our quick guide for genealogy is designed to help beginner and intermediate family history researchers alike by addressing basic questions about using the census for genealogy research and providing detailed summaries of the information found in each census year.

You’ll also find a quick reference table to help you easily identify which census year certain important pieces of information can be found in – such as a marriage date or immigration year. You’ll also find direct links to each census collection where it can be searched for free online.

What is the U.S. Census?

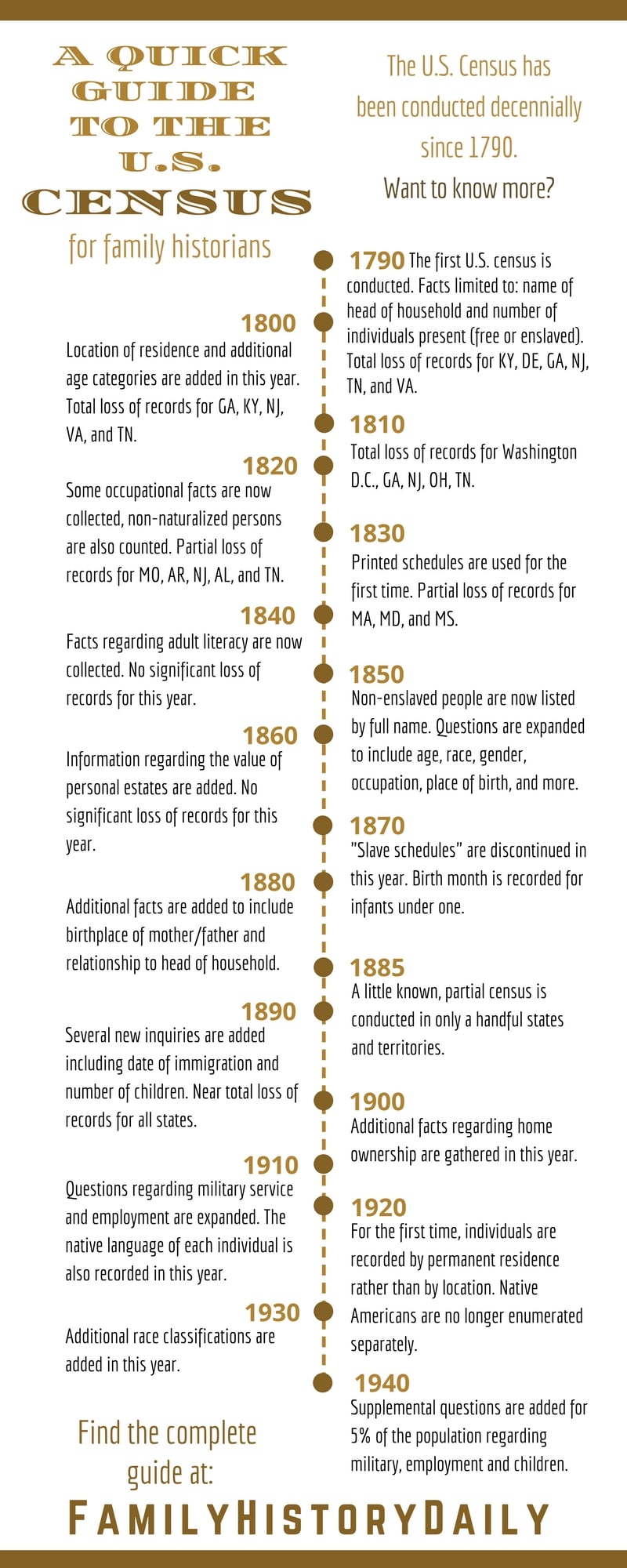

The U.S. Census has been conducted decennially since 1790 and is mandated by the constitution to count every U.S. resident. Census records are restricted for a period of 72 years, which makes the 1940 census the most current available collection. In 2022 the 1950 census will be released for public use.

U.S. Census records are one of the core collections for family historians since they provide regular data one can use to trace their ancestors.

What genealogy information is available in U.S. census records?

The U.S Census has evolved since first enacted in 1790. Censuses conducted prior to 1850 contain only very basic information, such as the name of the head of household and number of males and females in the home. Beginning in 1850, enumeration schedules were expanded to include elements such as age, birth place, military service, employment, and even health information.

Few census schedules are identical and both the type of data collected and method of collection may differ by year. Several years also include special schedules for different segments of the population.

This guide provides a detailed summary of what is available in the population schedules for each census year as well as a quick reference table that will help you find certain pieces of genealogical information by the years that it was included.

Although the census can provide many details about your family, always keep in mind that the data was provided by individuals and is prone to error. Enumerators also made mistakes, and transcriptions errors are common. When searching for your ancestors in the census account for variations and misspellings in first and last names as well as ages and other data.

How do I search U.S. census records online?

The United State Census Bureau conducts the census and the records are maintained by the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). Records can be accessed at the National Archives building in Washington D.C. and regional facilities throughout the United States. NARA does not currently have digitized census information on their website, but these records are available for free through partnering organizations online.

FamilySearch.org is completely free to use and provides access to most U.S. census records online. We have included links to each census year through FamilySearch in this guide.

Some census records can also be found free of charge through Ancestry.com, while others can only be accessed with a paid subscription. MyHeritage also offers all census records as part of their subscriptions.

According to the NARA all census records will eventually be digitized from microfilm and available to search through the NARA website as well.

U.S. Census Quick Reference Table

The following table provides an easy way to identify what pieces of information you can find in different census years. For instance, you might like to know which census years included a marriage date and the table will help you quickly locate that information.

This table does not include all of the information available in the census. You will want to read the full guide below it for more detailed information. The guide includes full descriptions for each census year – including all relevant information that was collected, official enumeration date and details on special schedules.

Find the full guide below the table.

PLAN - PRICE

Description

All Household Members

Birth Place

Age or Birth Date

PLAN - PRICE

Description

Marriage Date

Immigration

Complete Address

PLAN - PRICE

Description

Parents' Birth Places

Occupation

Special Schedules

Guide to Family History Information in Each U.S. Census

Below you will find a complete breakdown of the information found in U.S. Census records for each year. We have covered all census years starting from the first enumeration in 1790 until the most recent census that has been released to the public – 1940. We have included most of the information relevant to family historians, although some details may have been excluded in an attempt to keep this guide as concise as possible.

For easy reference we have included the census year, official enumeration date, questions asked, known loss of records,, additional schedules and links to the collections on FamilySearch (where you can search and view them for free).

Note on Official Dates of Enumeration: We have included the official date of enumeration since this is an important element of using the data you find. When an enumerator recorded the answers to questions, all answers were to be based on this date (such as age). Generally, you should use this date instead of the date the census record was actually recorded on when considering the information. For more details about the instructions enumerators had to follow and how this influences the information you find in a census please see this article.

Note on Locating Addresses: It should be noted that addresses can be found in some later census years by looking for the street name (on the far left) and the house number (recorded next to the head of household). Dwelling and family number found in other census years reflects the order of visitation by the enumerator and not the house number of the family. Persons were often recorded by temporary residence (where they worked or visited) until the 1920 census when permanent residence was used.

Note on Nonpopulation Schedules: In addition to the various population schedules detailed below, the United States also created a variety of schedules related to business and agriculture. Although the purpose of these schedules was not to record personal details you may still find the names of ancestors and their business/farm information. Please see this page on the National Archives for more about these schedules. Ancestry has some of these records available with a paid subscription.

1790 U.S. Census

1790 U.S. Census records recorded:

- the name of the head of family

- number of free white males 16 and up

- number of white males under 16

- number of females

- number of other free persons

- number of enslaved persons

- state, county and city

Official Enumeration Date: August 2nd

Loss of Records: Total loss of records in the following states/territories: DE, GA, KY, NJ, TN, VA.

1800 U.S. Census

1800 U.S. Census records recorded:

- the name of head of family

- state, county and city

- number of free white males by age group

- number of free white females by age group

- number of other free persons

- number of enslaved persons

Official Enumeration Date: August 4th

Loss or Records: Total loss of records in the following states/territories: GA, KY, NJ, VA, TN.

1810 U.S. Census

The 1810 U.S. Census was identical to 1800 population schedule and recorded:

- the name of head of family

- state, county and city

- number of free white males by age group

- number of free white females by age group

- number of other free persons

- number of enslaved persons

Loss of Records: Total loss of records in the following states/territories: Washington D.C., GA, NJ, OH, TN.

Official Enumeration Date: August 6th

1820 U.S. Census

1820 U.S. Census records recorded:

- name of head of family

- state, county, city

- number of free white males by age group

- number of free white females by age group

- number of male slaves by age group

- number of female slaves by age group

- number of free “colored” persons by age group

- number of nonnaturalized foreign persons

- number of persons involved in agriculture, commerce, and manufacture (enslaved persons included)

Official Enumeration Date: August 7th

Loss of Records: Partial or total loss of records in the following states/territories: Arkansas Territory, Missouri territory, NJ, AL (half), TN (approx. 20 eastern counties).

1830 U.S. Census

1830 U.S. Census records recorded:

- the name of head of family

- state, county, city

- free white males/females by age group

- male/female enslaved persons by age group

- free “colored” male/females by age group

- number of individuals identified as “deaf or dumb” (white and slave or “colored”)

- number of blind individuals (white and slave or “colored”)

- white nonnaturalized foreign individuals

This is the first year standard printed schedules were used.

Official Enumeration Date: June 1st

Loss of Records: Partial loss of records in the following states/territories: MA, MD, MS.

1840 U.S. Census

The 1840 U.S. Census recorded the same information as the 1830 schedule with the addition of an inquiry of the number of illiterate individuals over the age of 20. Please see 1830 entry for additional information.

Official Enumeration Date: June 1st

Loss of Records: No significant loss of census records known.

1850 U.S. Census

The 1850 U.S. Census was the first year that all individuals were listed by name rather than just head of household (Native Americans and slaves excluded).

Separate schedules were used for slaves and these persons continued to be identified only by the name of the person who enslaved them. Sometimes their employer was also listed if they worked externally. Native Americans on reservations and unsettled lands were also excluded.

The population census for free persons recorded the number of dwelling and family (number is the order visited – not the house number), and the following:

- full name

- age

- gender

- race

- occupation if over 15 yrs.

- value of real estate owned

- place of birth (state or country)

- if individual was literate

- is person was married or in school within the last year

- if person was “deaf, dumb, blind, insane, idiotic, pauper, or convict”

The 1850 U.S. Census Slave Schedule recorded:

- the name of the slaveholder and sometimes employer

- total number of enslaved persons

- their gender, race, and whether the individual was identified as “deaf, dumb, blind, insane, or idiotic.”

- number of uncaught escaped slaves in the last year (per slaveholder)

- number of slaves freed from bondage within the last year (per slaveholder)

The 1850 U.S. Mortality Schedule collected information about those who died between June 1849 and May 1850. Mortality schedules were also conducted with the 1860, 1870, 1880 and 1885 censuses and recorded deaths from the previous year (from official enumeration date). FamilySearch does not currently offer them but we have written about how to access these schedules for free here.

Official Enumeration Date: June 1st

Loss of Records: No significant loss of census records known.

1860 U.S. Census

The 1860 U.S. Census for free inhabitants collected the same information as 1850 census schedule with the addition of an inquiry of the value of an individual’s personal estate. A few Native Americans living in the general population (not on reservations) were included but enslaved persons are still excluded and appear without a name in the separate slave schedule.

The 1860 Slave Schedule was identical to the 1850 schedule (see above). This collection is not available on FamilySearch. It can be accessed on Ancestry.com only with a paid subscription.

A Mortality Schedule that recorded deaths was also taken. See notes for 1850.

Official Enumeration Date: June 1st

Loss of Records: No significant loss of census records known.

1870 U.S. Census

The 1870 U.S. Census was the first year that previously enslaved persons were listed in the main population schedule by name. Native Americans living in the general population (not reservations) are included in larger numbers for the first time.

This census recorded:

- full name

- state, county, city

- age

- gender

- race

- occupation if over 15 yrs.

- value of real estate/personal estate owned

- place of birth (state or country)

- if father of foreign born

- if mother foreign born

- month if born within the last year

- month if married within the last year

- if attended school in last year

- if can read or write

- is person “deaf and dumb, blind, insane, or idiotic”

- if male over 21 and denied right to vote

A Mortality Schedule that recorded deaths was also taken. See notes for 1850.

Official Enumeration Date: June 1st

Loss of Records: No significant loss of census records known.

1880 U.S. Census

1880 U.S. Census records recorded the number of family/dwelling in order of visitation and the following about each person:

- full name

- state, county, city

- race

- gender

- age (under one indicate month)

- relationship to head of household

- marital status

- was person married in census year

- occupation/trade

- number of months employed in census year

- place of birth

- father/mother place of birth

- if person attended school in past year

- if the individual was literate/illiterate

- if sick/disabled on day of census

- if the individual had one or more types of disabilities/injuries listed as “blind, deaf, dumb, idiotic, insane, maimed, bedridden, or otherwise disabled”

A special census schedule of “Defective, Dependent, and Delinquent Classes” was taken in this year and can be accessed through Ancestry.com with a paid subscription, but is not available for free online.

Native Americans in the general population were identified in the main census if they were not living on reservations. A “Special Census of Indians” was conducted in this year for those Native Americans who lived on reservations or who were nomadic. You can read more about that on Ancestry. The index is available with a free account on their site. Please note that this is a separate initiative than the later U.S. Indian Census Rolls (see below).

A Mortality Schedule that recorded deaths was also taken. See notes for 1850.

Official Enumeration Date: June 1st

Loss of Records: No significant loss of census records known.

1885 U.S. Census

The 1885 U.S. semi-decennial census is a little known partial census that was conducted in a handful of states. For more information please read our article on the topic. A Mortality Schedule that recorded deaths was also taken. See notes for 1850.

American Indian Census Rolls, 1885-1940

Although this collection is separate from the U.S. Federal Census it was such an important initiative that we felt we must include it. The Indian Census records were conducted each year (not every 10 years) by agents in charge of reservations and were sent to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs – although not all reservations are covered for every year.

Early records included English and/or “Indian” name, age and relationship to head of household. Beginning in 1930 records also included marriage information, degree of Native American blood and more.

You can read more about this census on the National Archives here. This page details exactly what the collection contains, what areas were covered in what years, and where to find the collection online.

Special Census of Deaf Family Marriages and Hearing Relatives, 1888-1895

This special census was conducted in the years 1888-1895 by E.A Fay for the Volta Bureau and collected names, occupations and information about deaf persons and their families. For more about this schedule please see Ancestry.com where an index is available free of charge.

1890 U.S. Census (almost totally lost, see notes)

The 1890 U.S. Census expanded inquires from earlier years to the include the following on a single form per family:

- dwelling/family number by visitation

- state, county, city

- number of families/persons per home and number of people in each family

- full name

- relationship to head of household

- race

- gender

- age

- marital status

- place of birth

- father’s/mother’s place of birth

- length of time in U.S.

- trade/occupation

- whether they were a servicemember/widow of Civil War

- whether naturalized

- marital status and whether married in past year

- if female, how many children/how many living

- number of months in school in past year

- number of months unemployed in past year

- literate/illiterate

- primary language spoken

In addition, questions inquired if person had acute illness, a variety of disabilities, or if person was “prisoner, convict, homeless child, or pauper.” In some cases an additional schedule was completed in reference to disabilities. Several questions were asked per family regarding home/farm ownership/debt.

Loss of Records: There is a near total loss of records for this year. Information on approx 6000 individuals still exists in small portions of the following states: AL, D.C., GA, IL, MN, NJ, NY, NC, OH, SD, TX

The 1890 Union Civil War Veterans/Widows special schedule was to collect information about Union soldiers but many Confederate soldiers were mistakenly recorded as well. Unfortunately, there was an almost complete loss of records for the states of Alabama through Kansas (alphabetically) and for parts of Kentucky. Remaining records can be very useful. See this page on FamilySearch for more information.

The Veterans schedule included the following information:

- name of veteran (include widow if veteran deceased)

- rank

- company

- regiment/vessel

- date of enlistment/discharge

- time in service

- address

- disabilities incurred

- additional relevant information

Official Enumeration Date: June 2nd

Read our article about accessing what’s left of the 1890 census here.

1900 U.S. Census

The 1900 U. S. Census collected the following information per person:

- full address (street and house number as well as state, county city)

- dwelling/family ordered by visitation

- full name

- relation to head of household

- race

- gender

- birth month and year

- age

- marital status and number of years married

- number of children/number living (mothers only)

- place of birth

- mother/father place of birth

- year of immigration/number of years in U.S.

- naturalization status

- occupation/profession

- literate/illiterate

- whether can speak English

- months of unemployment in past year

- months in school in past year

Several questions related to housing were asked including: rented or owned; if owned, was home mortgaged; if individual lived on a farm and this is the first year you can easily locate a full address. If individual lived on farm, ID number linking census record to corresponding agricultural schedule was listed (see note in this guide about nonpopulation schedules).

The 1900 Indian Schedule records can be found with the general population records and recorded information about Native Americans living on reservations and in the general population. The first section of the census schedule was identical to that of the general population, other than to indicate if the individual was wholly or partially dependent on the government. Read more about this schedule here.

This special schedule should not be confused with the American Indian Census Rolls detailed above.

An additional 10 questions on the Indian schedule inquired the following:

- “Indian name”

- tribe

- tribe of mother/father

- citizen status/year acquired

- fraction of lineage that is white

- if individual living in polygamy

- if individual taxed (living in white community or recipient of allotted land by federal government)

- if individual is citizen through land allotment

- and if home “movable or fixed”

Some additional questions were also asked of those living in AL, HI, and on military bases.

Official Enumeration Date: June 1st

Loss of Records: No significant loss of census records known.

1910 U.S. Census

The 1910 U.S. Census was very similar the schedule of 1900. Other than some changes in terminology the significant differences include: fewer questions related to disabilities; individuals were to indicate if they were a survivor of the Union or Confederate Army or Navy; and additional questions regarding employment (employer, employee, self-employed). An inquiry of an individual’s native language was a late addition and therefore indicated in columns 12-14 under “nativity.”

The 1910 Indian Schedule, found as part of the main 1910 census, was similar to the one conducted in 1900 with the addition of the following: percentage of white, black, Indian lineage; has individual graduated from educational institution, if so indicate institution; specific questions related to polygamous relationships; specifics of one’s living situation (land ownership, land allotment, is dwelling “aboriginal” or “civilized”).

Official Enumeration Date: April 15th

Loss of Records: No significant loss of census records known.

1920 U.S. Census

The 1920 U. S. Census general population schedule was similar to that of 1910 but somewhat shorter, excluding some items such as number of years married. Native Americans on reservations were not enumerated separately for the first time.

Information was collected as follows:

- street and house number as well as state, county and city

- dwelling/family by order of visitation

- full name

- relationship to head of household

- if home is rented or owned (if owned indicate if mortgaged)

- gender

- race

- age

- marital status

- year of immigration

- naturalization status/date of naturalization

- school attendance in last year

- place of birth and mother tongue

- mother/father place of birth and native language

- occupation/profession and place of employment

It was also asked if the individual is an employer/employee/self-employed (indicate which); if individual is English-speaking, and if individual is literate. Farmers were to indicate ID number for corresponding farm schedule (see information in this guide about nonpopulation schedules).

About Addresses: 1920 was the first year in which residents were recorded by permanent residence rather than by place they worked or visited. Those without a permanent residence were enumerated in the place they were at time of census.

Official Enumeration Date: January 1st

Loss of Records: No significant loss of census records known.

1930 U.S. Census

The 1930 U.S. Census was essentially the same as the 1920 schedule other than modifications to race classifications and additional marriage information that was added back in (age at first marriage). Individuals that were of mixed racial lineage that included white were to be classified as the other race except for Native American persons that had a small percentage and identified as white. In the case of mixed racial lineage of two minority racial backgrounds, individual was to classify as race of father.

The following states have a Soundex index in which surnames are grouped phonetically: AL, AR, FL, GA, KY, LA, MS, NC, SC, TN, VA, WV.

The 1930 Merchant Seamen schedule recorded individuals on vessels on census day and recorded the following:

- vessel

- owner/address

- port

- full name of seaman

- state or country of birth

- occupation

- whether a veteran/specific war

- address of next of kin

This schedule recorded vessels in the following states: AL, CA, CT, FL, GA, IL, IN, LA, ME, MA, MD, MI, MN, NH, NJ, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, TX, VA, WA, WI.

A special Unemployment Census was also taken during this year but is not available.

Official Enumeration Date: April 1st

Loss of Records: No significant loss of census records known.

1940 U.S. Census

The 1940 U.S. Census expanded information collected on employment and included an additional 16 supplemental questions given to 5% of the population (see notes below).

The following data was collected in the main census:

- street and house number as well as state, county and city

- household in order of visitation

- full name, relationship to head of household

- gender

- race

- age

- marital status

- school attendance in last year

- highest level of education

- place of birth (if not U.S., indicate if U.S. citizen)

- occupation (see additional information below)

- place of residence on 4/1/1935 (if not present dwelling, additional information was collected on previous dwelling), city/town/village of residence, state, country

- if home is rented or owned (indicate value) and if residence is a farm

For persons 14 and older, there were several inquiries about employment for the week of March 24-30, 1940. Individuals were to indicate which of the following applied to them and provide various details: compensated work in private or nonemergency government sector; assigned to public emergency work; seeking work; or other (housework, school, unable to work or other).

Additional information collected included: individual’s occupation/profession, industry or business “class of worker,” number of weeks worked in 1939, total wages, additional income over $50 from other sources, corresponding ID number for Farm schedule, if applicable.

This is also the first year that the housing schedule was conducted.

The supplement questions were included in an additional section at the bottom of each census page and dealt with military service of individual or family members, employment/retirement income questions, marriage and childbearing (female only). Supplemental questions were included for approx. 5% of population. Read our article about this topic here to determine if your ancestors were included.

The following states have a Soundex index in which surnames are grouped phonetically: AL, AR, FL, GA, KY, LA, MS, NC, SC, TN, VA, WV.

Official Enumeration Date: April 1st

Loss of Records: No significant loss of census records known.

Other Census Articles from Family History Daily:

This Information Will Make You Question Every Census Record You’ve Ever Collected

The Forgotten Federal Census of 1885 Can Be Found Online for Free

What Really Happened to the 1890 Census?

Thousands of 1890 Census Records DO Still Exist: Here’s How to Find Them for Free

The ‘Secret’ Details in the 1940 Census You May Be Missing

Additional Resources:

U.S. Census form headers and additional information from FamilySearch

Through the Decades: census information from the United States Census Bureau

Thank you to Family History Daily Associate Writer Jessica Grimm for her hard work making this guide possible.

Image: Census enumerator in New York, 1930.

What is the timing of the Agricultural Schedules?

thanks for this informative summary of the different US censuses. However, you omitted one piece of data found in the 1930 census that I find very useful: only three censuses (1900, 1910, 1930) give information suggesting WHEN couples were married, and 1930 is unlike 1920 in that it indicates “age at first marriage”, which can be tricky since it’s not always the _current_ marriage, just the first one.