By Bridget M. Sunderlin, CG®

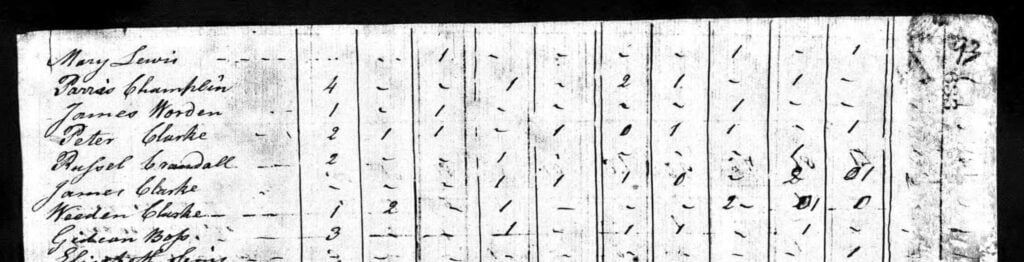

In this guide we’re going to learn how to harness one of the most underused genealogical resources of the late 18th and early 19th centuries: the U.S. Censuses of 1790 to 1830. These gems can be a bit daunting with their tick marks and handwritten surnames, but they can contain some very helpful information when used correctly.

I admit that these older population surveys can be scary, and don’t contain the same rich detail as later censuses, but know that there is a time and a place to use them. When strategically correlated with other available records, these early census rolls can truly connect 19th century families to one another and to their communities.

What do the 1790 to 1830 Censuses Have to Offer?

The very first census of the United States was taken in August of 1790, not long after George Washington was appointed leader and chief. This federal task required that every household within our new country be visited and tallied. The resulting forms were then posted in two of the most public locations within each jurisdiction for all to see.[i]

In 1790, marshals assigned to the visitations were given a list of questions to ask. See the chart that follows. The only name identified was that of the head of household. These individuals were listed by ward, district or area of residency. The date was included. All other responses were represented by tally marks.

This may not seem like much information but, when we can compare it in a variety of ways, we can learn a few things about a family’s structure as well as its economic status. Our first should be to compare other heads of households listed within the area to identify neighbors and family. We may see surnames that appear later in our tree through marriage. These community members may show up as witnesses within our ancestors’ land and probate records. If our ancestor held slaves, while others did not, this could indicate wealth, as well as occupation.

Relationships were not indicated on this census, nor any U.S. censuses until 1880. When faced with this lack of evidence, family historians are left to infer or hypothesize relationships. This tasks us with locating other sources to compare these findings to, such as church, land, tax or probate records, in order to support our hypotheses.

Additionally, any age-related information that we pull from census records of this type can only be ranges. We are left again to compare our findings to other sources, such as baptismal and marriage records. Before we can begin to visualize a family’s growth within a geographical area, we may need to evaluate the ages of household members across decades of census records.

The Censuses of 1800, 1810 and 1820

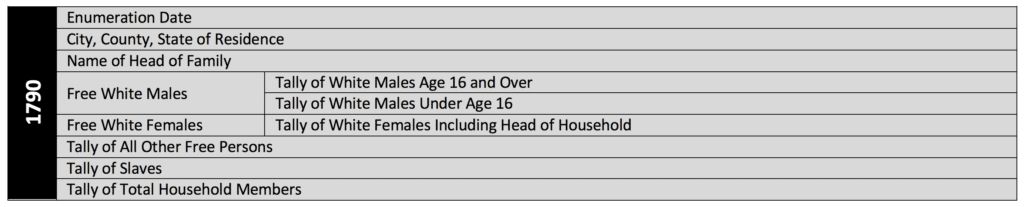

The questions asked by marshals on the U.S. censuses of 1800 and 1810 were identical in nature. New to these census questionnaires were age segments for all free white males and females of the household. Again, the head of household was the only named individual.

This addition of age ranges allows researchers to truly compare families across time, to make inferences about relationships and birthdates. These must be correlated, not only with families you have identified as yours but also other families, to resolve potential conflicts. Pay close attention to places of residency, slave ownership and other factors to ensure that you are comparing apples to apples, and not introducing a lemon.

When comparing census records, timelines can assist your efforts. This tool will help you to see changes across the decades, such as the death of the head of household, and children becoming heads of their own households. Add other record types such as land purchases and probate records to support these changes. Learn more about timelines here.

Census records should never be used alone to prove vital events such as birth, marriage and death, nor relationships within families. Keep this concept in mind when you work with census records after 1830, too. For a quick overview of other records to compare the census to, read Why You Should Never Rely on “Facts” You Find in the Census and What to Do Instead.

1800 & 1810 Census Questions

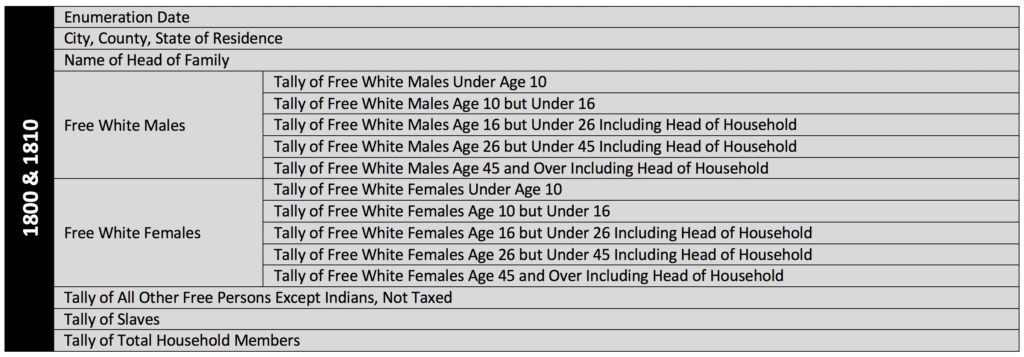

By 1820, the questions posed to each family grew in depth and specificity. For the first time, foreigners, or aliens were identified, which introduced potential new U.S. residents, whose census records should also be matched with those pertaining to immigration.

Not only were age ranges tallied for free white residents, age ranges were identified for slaves and free colored persons. These individuals were classified by gender as well, which allows the researcher to compare age across time for all members of a household. This is a great technique to use, especially when matched to tax, probate and slave schedule records.

All inhabitants engaged in agriculture, commerce and manufacturing were counted as such, which offers insight into occupational differences between families. This information should be used to refine your ancestral research not only through surname and residency, but also employment.

1820 Census Questions

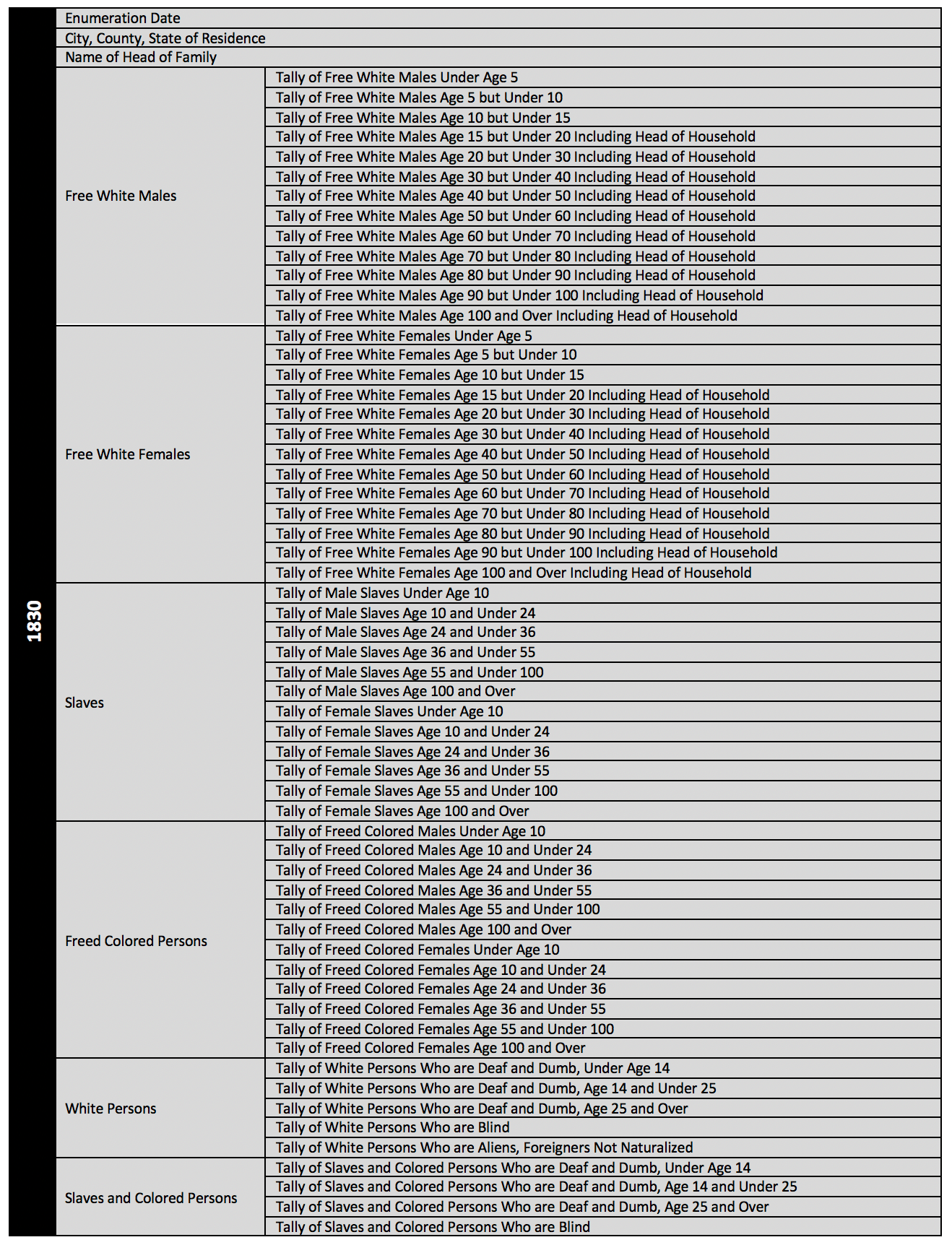

The Census in 1830

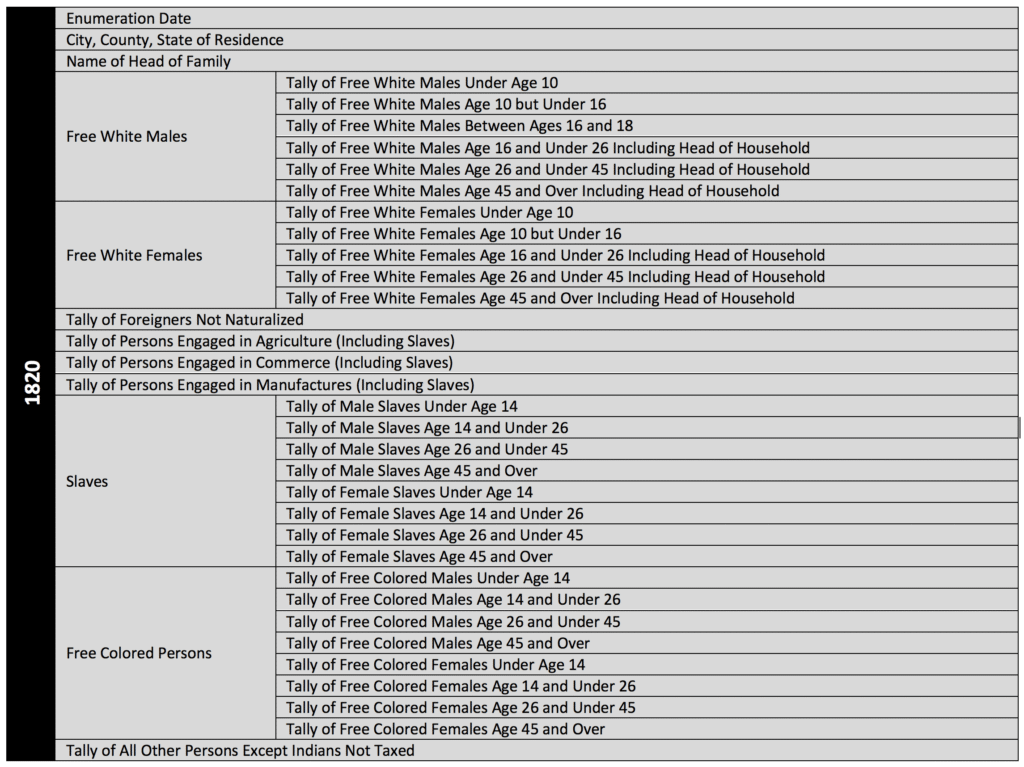

Genealogists throughout the world will be happy to know that marshals utilized a uniform, printed schedule when tallying the 1830 U.S. census. These boilerplate documents offer an ease of readability never experienced before. Columns and rows of tally marks lined up. Less handwritten notations increase legibility overall.

Unique to the 1830 U.S. census was a more precise breakdown of age ranges. Instead of the previous fifteen-to-twenty-year range, ranges were shortened to ten years. The ages of children were broken down farther, to five-year increments. This precision allows the genealogist to more closely pinpoint predictions for younger family members.

This same specificity does not apply to slaves and freed colored persons, however. Instead, a fifteen-year range is offered, similar to that of age ranges offered in censuses that preceded 1830.

A new category surfaced regarding residents with disabilities, specifically deafness, dumbness and blindness. These were tallied for all household members, although no differentiation was made to separate slaves from freed colored persons, nor male from female, within the residence. This information has the potential to add personal characteristics to ancestors but, unfortunately, it lacks a link to specific individuals within the home.

1830 Census Questions

Where is the Best Place to View These Early Census Records?

Many online sites offer you the ability to view census records online and I usually recommend FamilySearch, since it’s free. However, if you already have a subscription to another genealogy site like MyHeritage, Ancestry or Findmypast, you will find the records there as well.

After these services were reviewed to identify which had the cleanest digital image of these early census records, almost hands down, Find My Past won. The backgrounds were clean. The 1830 headings were clear. The contrast between black tick marks and white paper made these quite legible.

The service with the best tabulation would have to be Ancestry. They have an added “within view” transcript that makes it so easy to see what the tick marks mean. I’ve yet to find an error in these, but one should not discount that possibility. Therefore, check them against the original image. With these handwritten censuses, we rarely see the heading that pertains to each tick mark, but our friends at Ancestry have solved that with the added transcript.

FamilySearch wins for the quickest way to identify names surrounding your ancestor. They have a transcript bar at the bottom of each page where you can easily read head of household names in order. Again, transcriptions are creations from the original, so you should always check them against the original document itself. FamilySearch’s images were as clean and clear as those at Find My Past, but it was difficult to navigate the tally headings.

How Best to Harness These Censuses in Your Research

Due to the fact that you are basically flying without instrumentation when viewing census records from 1790 to 1830, you simply must test, test, test the source. These early census records lack so much information, that experts always correlate them against one another, as well as against other records from the same time. Professional historians test heads of households of the same name by comparing all known facts to resolve conflicts. This requires exhaustive research of all historically appropriate record groups.

Use maps from every decade to get the lay of the land. Start your search at the Library of Congress. Locate the homesteads of all neighbors. Connect your ancestors and their neighbors to specific places. This will help you to eliminate families that do not apply.

One of the best aspects of these earlier censuses may be the fact that populations were smaller. People knew each other. Communities were tighter. Use this in a positive way by building communities of people beyond just your ancestor. Look for witnesses and sponsors to your ancestors’ events, such as baptisms and wills. Connect them to your family. Identify your ancestor’s precise place within his or her community.

Compare censuses to one another across time to see repetition and the growth of your family. Connect all families with the same surnames by identifying those relationships. Link fathers and sons to one another. Link brothers to one another. Be open to marriage names that will link sisters. Be open to two sisters marrying two brothers. Think about how close families lived to one another for marriage to occur.

Take a bold step into the past, and truly investigate these earlier census records. You will not be sorry. Use them to locate the exact place that your ancestor lived. Identify their neighbors, by reviewing each and every entry on the census. Jump to other records from the time, and compare the census to church, tax, land, military and probate records.

If you want to learn more about the U.S. census as a genealogical resource, visit The Ultimate Quick Reference Guide to the U.S. Census for Genealogy and 9 Surprising Things About the U.S. Census Every Genealogist Should Know. If you need further guidance with colonial and early American records, read 4 Free Places to Research Your Colonial American Ancestors.

Bridget M. Sunderlin, CG® practices in Maryland. She is the owner of Be Rooted Genealogy, where she specializes in Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York, Ireland, and Scotland research.

[i] “Decennial Census Official Publications,” U.S. Department of Commerce, US Census Bureau (https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/decade/decennial-publications.1790.html : accessed 11 September 2020), web page, “Information about the 1790 Census.”

Last year I learned about 90-60 Census Workbook by Donna Cox Baker, owner, Genohistory.com and Golden Channel Publishing developed the Early Federal Census Worksheet which is an excellent tool to use to help sort out these early censuses. The worksheet covers the 1790 to 1860 census. A must have!

Thank you so much! I’ve about given up on finding my 2nd great grandfather, as what little information I have on him has no sources. I will use these census tips to start over and be more thorough.