By Bridget M. Sunderlin

Upon first glance, the U.S. Census appears to be a powerful source for genealogists. With its wide array of information, from ages and family relationships to countries of origin, it seems to be overflowing with facts that can help us follow the lives of our ancestors across time. Yet, I say, “Researchers, beware!”

“Why?” you ask. To answer this question I will take a look at the purpose of the census, examine the Genealogical Proof Standard as it relates to census research, look at an example of a common census pitfall and present a table that will help you locate additional records to verify census details. Although this article focuses on the U.S. census, the guidance provided can be applied to many population schedules around the world.

The Purpose of the U.S. Census

From its inception in August of 1790, the goal of the U.S. Census was to visit every household and post the results in every jurisdiction for all to see. Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution, requires that enumeration be made every ten years. This data informs the disbursement of federal funds and more importantly, the number of seats that each state has within the House of Representatives.

When choosing evidence to prove a genealogical question, we must be aware of the purpose for the record. In the case of the census, it documents the number of people in a home and their general or precise location. Despite its usefulness to genealogists today, it was never meant to accurately document other details such as age or marital status. No substantiating evidence was required by enumerators or census marshals when they visited the homes. Residents simply answered the questions posed as best they could (or would), and this led to many inaccuracies.

You can read more about the historical rulebook for enumerators here.

It is important to note that the head of household was not always the person who answered the questions posed. Often, it was the wife, but it could also have been a boarder or even a neighbor who acted as informant. Illiteracy would have greatly impacted the process.

Questions and responses were oral exchanges. The informant would rarely have reviewed the written results for accuracy. Many immigrants new to the United States spoke only their native language, therefore communication between the marshal and the families was most assuredly not as seamless as we might have hoped.

The quality of enumerators or marshals would also have varied. Some were appointed to the position. Some worked with great speed, valuing quantity over quality. They were often required to duplicate the schedules by hand, which could have led to even more inaccuracies.

Taking all of these things into consideration, we almost immediately become cognizant that we may actually have mined fool’s gold, and not that of the 24-carat variety, when we drew information from a census record. And that’s why we need to go through a process of verification to make sure our work is credible. The Genealogical Proof Standard (GPS) can help us with that.

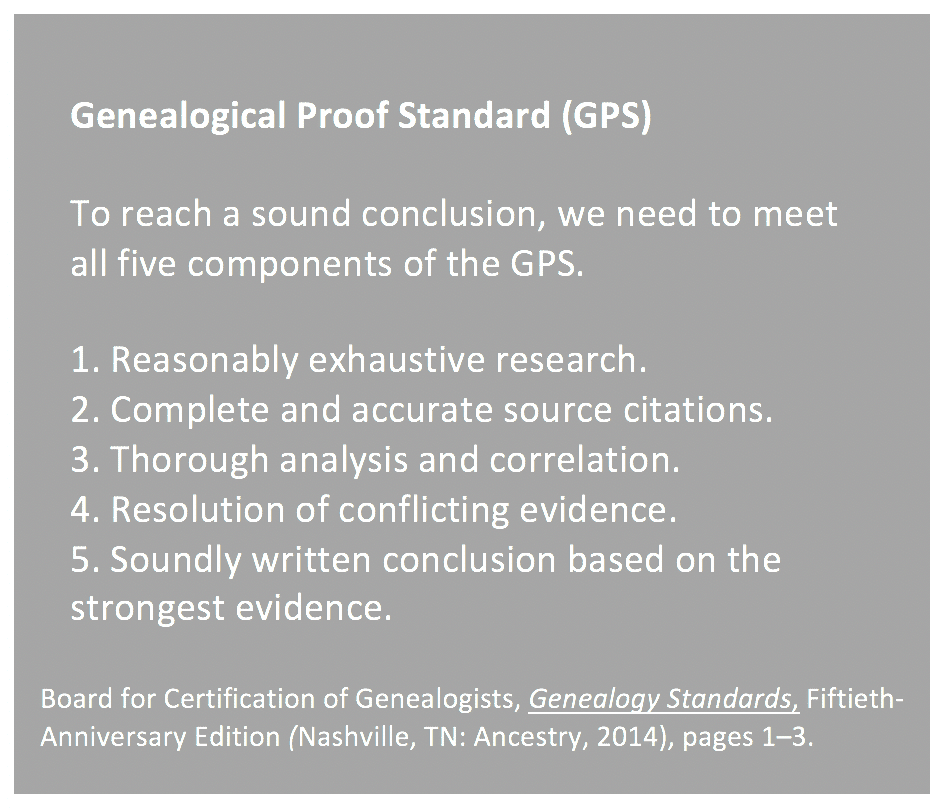

The Genealogy Proof Standard and How it Relates to Census Research

The Genealogy Proof Standard measures the quality of our research and requires us to go through a series of 5 steps to ensure that we have done everything we can to make sure our work is correct.

The first step is to involve ourselves in thorough or exhaustive searches per research question. This requires our evidence to be supported by more than one source, and the source should be the one created closest to the time of the event.

The census may certainly record evidence of your ancestor’s residence, but would not be a quality resource for proving their birth date or place, for instance. Why? A birth date recorded years later by your wife, who was not there when you were born, could be incorrect or at the very least, inaccurate. She only knows what you told her about your understanding of your birth. Plus, census questionnaires usually asked only for your age at the time of enumeration. This evidence is not specific, nor is it from the time of origin.

Thoroughness would also require the genealogist to read several pages within the census record instead of simply that of the ancestor, in order to locate all evidence, including neighbors, and other family that may be connected.

Complete and accurate citations of all sources must be present as well. This requirement again, tasks you with utilizing multiple interdependent sources to prove your research question. Each source would need to be analyzed and compared to other sources used to prove the research question. Comparison requires researchers to question the validity of the evidence by measuring it against other evidence. Is it accurate? Was it created at the time of the event? Did a reputable and objective participant craft it?

In order to meet the GPS, all evidential conflicts must be resolved and you must create a sound conclusion based on the strongest evidence available. To reach this requirement, the census must not be used as an original source for anything more than a few details and all of the information collected from it should be compared to and verified with other records.

Let’s look at an example of how easy it is to be misled by a census.

Putting the 1900 Census to the Test

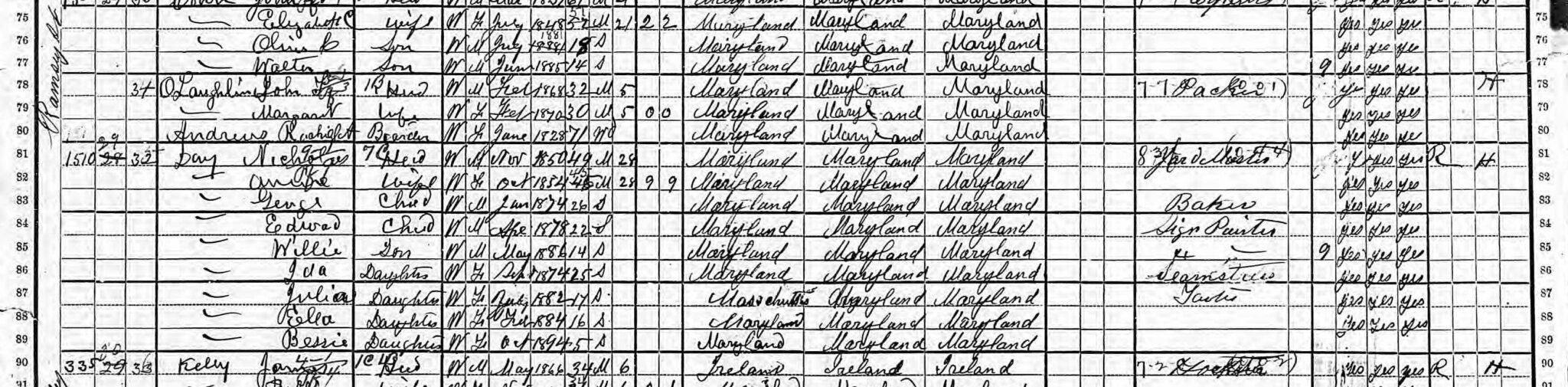

“Census and Voter Lists” Ancestry.com, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed 15 January 2019), online record search, Nicholas Day, 1900, page 4 of 34, Enumeration District 260, Baltimore Ward 20, Baltimore City (Independent City), Maryland; crediting “NARA microfilm publication, Roll T623_617, page 2B.”

As shown in the census image above, Nicholas Day was the head of household at 1510 Ramsay Street when he and his family were enumerated in June 1900. He was born in November 1850 and was age 49. He and his wife Annie had been married for 28 years. She was born in October 1854 and was listed at 45 years of age.

According to this census, Annie was the mother of 9 living children. With only 7 listed within this document, we might assume that two of Annie’s children were living on their own. Conversely, in the 1910 census, Annie claimed to have given birth to 11 children, with 7 living. Through comparison of original birth and death records, it has been proven that Annie had 11 children, 8 of whom were alive in 1900. Son Nick and daughter Gert were living on their own at that time. Their youngest, Bessie died in 1908, lowering the number to 7 by 1910.

Ah! But you say that 7 plus 2 equals 9. That may indeed be true, but there is at least one more significant inaccuracy left in this census record. It is the misidentification of Julia as the daughter of Nicholas and Annie Day. She was not. Notice her place of birth. Nicholas and Annie had no other children born in Massachusetts. It required several original records to disprove this one incorrect statement. Julia was actually their son George’s fiancée. They married three days after this document was written.

In addition, Julia’s birth information was transposed with Ida’s, who was actually born in Maryland in July 1882. Based on the number of living children listed and other inaccuracies, it is doubtful that Annie acted as the informant on this census record. Perhaps Nicholas did?

Of all the evidence located on this record, very few would be considered original in nature. The address, if accurate, would be original as this was the house the enumerator visited. The relationships could be considered original, although note that within this home, they were incorrectly documented or identified. The number of citizens living in the house would also be original. See the added notations “7C” and “9” that denote the number of people within this household. These were the most important details to the enumerator.

With this example in mind, it seems only prudent to suggest that using the U.S. Census as an original source for every detail held within it is not a wise idea. Instead, use the census as a jumping-off point to assist you as you gather more original evidence, and secondary sources, that will corroborate or debunk your research questions. Use the GPS as your guide in this process.

The following research aid offers you a series of facts found within the U.S. census and then suggests additional records that will help you verify this information. Use the information you’ve found in censuses to locate an original record (or multiple secondary sources if none are available) for that fact and then analyze your evidence after you have completed your research to make sure everything makes sense. Be open to completing further research if you encounter conflicting evidence, much as we were required to do with Julia Day.

Records You Can Use to Verify Census Evidence | ||

Fact Found on Various | Original Record Where the Fact May Also Be Found | Additional Sources Where This Information Can Sometimes Be Located |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I know this process may seem daunting, but to build an accurate family tree it is necessary to be cautious about what records we trust. We must always take the time to verify the information we choose to add to our files and share with others.

By looking for additional records to verify “facts” you have found in a census you will not only have a more credible tree but you will, no doubt, uncover many new pieces of information about your ancestors.

Also read: The Ultimate Quick Reference Guide to the U.S. Census for Genealogy or find more census articles here.

Bridget Sunderlin is a professional genealogist serving clients in and around Maryland with a Master’s in teaching. She has been actively researching her Irish roots for well over 30 years. Throughout her research, she has come to find that her family actually hails from all of the countries within the British Isles. In 2017, she visited some of her ancestral lands, meeting quite a few Irish and Scottish cousins along the way. Ms. Sunderlin believes that the act of researching one’s family history helps us to “be rooted.”

Image: “Man seated, taking U.S. Census, and four Winnebago Indians standing, in front of tent.” c1911. Library of Congress.

You don’t know if she was even asked the question of where she was born or whether the census taker simply wrote Texas for everyone. The quality of the information was very much dependent on the effort taken by the census taker and sometimes their ability to write.

Another good secondary source to verify census information is a passport application. Sometimes an individual doesn’t even know correct data about himself. My grandfather firmly believed that he was born in Penn Yan, Yates County, New York in 1872. He was correct about the year. He just missed the 1971 census. After a long search, I found his parents in the 1871 census, in Hector, Schuyler County, New York — just across Seneca Lake from Penn Yann. From there I could find birth records in State Vital Records, and prove his birth.

I was born in Speed Kansas on May 10, 1939 to Floyd Dean Fix and Mary Emma Fischli Fix.

Also, people lie, even more so to the Govt.!

My own paternal grandmother told the Census taker she was born in Texas during the Census of 1930. He apparently overlooked her distinctly Irish brogue because she was born in Omagh, Tyrone, Ireland!

One man’s facts are another’s fallacies. Records are not absolute proof of anything, nor are histories.

My favorite examples are a) a 1930 OH census naming my mother and her older sister as daughters to an uncle, while on another census form they are listed as my grandparents’ daughters, each done from different locations … and b) my 2 birth certificates– the first my original birth certificate with mother’s input in which she did not use her correct given name, gave incorrect ages for she and my father, a wrong city of birth for my father; the second my amended adoptee birth certificate listing adopters names as my parents and replacing my real name with something apparently the adopters chose… dated five and a half years after my birth in a state far distant from that of my birth and minus any of the normal entries found on a usual birth certificate done in hospital; shortly after a child’s birth ..and, signed by a judge. My paternal grandmother has an entry in her bible for the marriage of my parents… the date is incorrect … my father was serving on a naval vessel in the south Pacific on the date listed, this information from a USN muster roll recorded on that date.