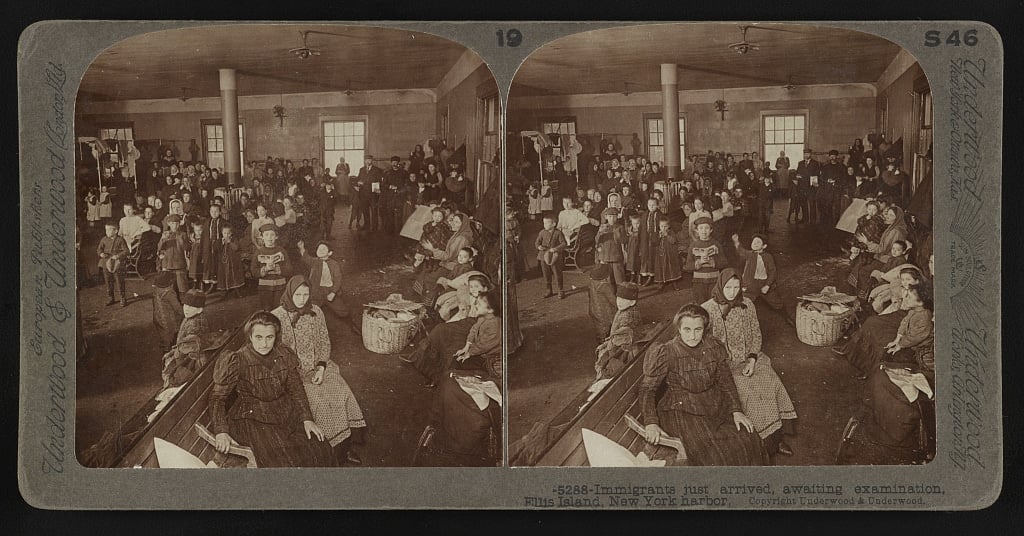

Nearly every one of us has ancestors who lived, worked and died in a country not our own. And, for this reason, we sometimes need to leave our comfort zone behind and head into unfamiliar territory with our family history research. Much like an ancestor disembarking in New York City and asking “What are my next steps in this new land?” international genealogy research can be confusing and daunting. But the journey is worth the trouble, and with some guidance you might be surprised what you can discover.

Getting Started With International Family History Research

Imagine finding an old grave or homestead in an ancestral town, making sense of why your family has the surname it does, or finally discovering if the story of your great, great grandfather’s bizarre occupation was really correct. While this guide does not cover specific countries (you’ll want to check out our online courses for that), it will help U.S. researchers understand how to begin the process of international research.

How do I start researching my ancestors overseas?

Always begin your research by starting in the present and working your way back into the past. Before you even think about researching in the old country, you need to get a good start on your research in the United States (the tips in this guide will be useful to those who are researching ancestors who immigrated to countries other than the U.S., but we will be focusing on those who did).

Begin by selecting one ancestor whose family origins you are most interested in and form a genealogical question about that individual. An example might be: “Who were the parents of Archibald Young, who was born in Scotland and married Agnes Campbell in Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania in March 1868?”

You will want to select a person who you know emigrated from their origin country and can provide the bridge you need to foreign research. If you are just starting your tree, this may mean that you need to spend some time discovering who these people were by focusing on more recent genealogical research first. There are many articles on this site to help.

Then, chart what you know about this ancestor and his or her family within the U.S. Evidence Chart below.

| U.S. Evidence Chart | |

| Ancestor Name | Spouse’s Name |

| Birthdate | Spouse’s Birthdate |

| Birthplace | Spouse’s Birthplace |

| Baptism Date and Place | Marriage Date and Place |

| Religion | Child 1 Name |

| U.S. Residence/s | Child 1 Birthdate and Place |

| U.S. Occupation/s | Child 1 Baptism Date and Place |

| Death Date | Child 2 Name |

| Death Place | Child 2 Birthdate and Place |

| Emigration Date and Place | Child 2 Baptism Date and Place |

| Ship Name | Child 3 Name |

| Occupation Listed on Passenger List | Child 3 Birthdate and Place |

| Age on Passenger List | Child 3 Baptism Date and Place |

| Others Traveling with Ancestor on Passenger List | Child 4 Name |

| Others with Same Surname on Passenger List | Child 4 Birthdate and Place |

| Others from Same Place on Passenger List | Child 4 Baptism Date and Place |

| Immigration Date and Place into U.S. | Child 5 Name |

| Naturalization Date and Place in U.S. | Child 5 Birthdate and Place |

| Other Information from Naturalization Papers | Child 5 Baptism Date and Place |

| Father’s Name | Child 6 Name |

| Mother’s Maiden Name | Child 6 Birthdate and Place |

| Sibling 1’s Name | Child 6 Baptism Date and Place |

| Sibling 1’s Birthdate and Place and Baptism | Child 7 Name |

| Sibling 2’s Name | Child 7 Birthdate and Place |

| Sibling 2’s Birthdate and Place and Baptism | Child 7 Baptism Date and Place |

| Sibling 3’s Name | Child 8 Name |

| Sibling 3’s Birthdate and Place and Baptism | Child 8 Birthdate and Place |

| Sibling 4’s Name | Child 8 Baptism Date and Place |

| Sibling 4’s Birthdate and Place and Baptism | Additional Notes |

| Sibling 5’s Name | |

| Sibling 5’s Birthdate and Place and Baptism | |

| Sibling 6’s Name | |

| Sibling 6’s Birthdate and Place and Baptism | |

| Sibling 7’s Name | |

| Sibling 7’s Birthdate and Place and Baptism | |

| Sibling 8’s Name | |

| Sibling 8’s Birthdate and Place and Baptism | |

Help with developing research questions, as well as printable and digital charts, can be found here.

What if I do not have all the answers in the chart above?

If you were unable to answer at least 70 percent of this U.S. Evidence Chart, your American research is incomplete. This is a critical step. Without these answers, your work outside of the U.S. may be nearly impossible. Be aware that America may have more records than the old country, and this is especially true when you realize how and when precise records came into existence. To be successful at international research, you need American records to direct your search to the specific place of origin for your ancestor.

For those of you whose U.S. Evidence Chart is incomplete, go back and resume your U.S. research. Use the checklist of U.S. Records Groups below (or grab the helpful checklist by entering your email at the top of this page) to find the answers you need. Move on to the next question after you have exhausted these.

| U.S. Record Groups | ||||

| Baptism Records | Birth Records | Cemetery Records | Census Records | Court Records |

| Death Records | Directories | DNA | Immigration Records | Land/Property Records |

| Marriage Records | Military Records | Newspaper Records | Probate/Wills | Tax Records |

What do I do if I hit a brick wall with my ancestor?

Your ancestor’s passage to America was paved by those who came before. Siblings, cousins and other relations formed a chain of opportunity and income that your ancestor employed to leave the old country. Your U.S. Evidence Chart, if filled in thoroughly, should begin to open your eyes to some of these relation’s names.

One of the most important reasons for knowing these relatives is to use their records to help identify that critical place of origin. If records are scarce for your ancestor, they may not be so for his brother, or his cousin. If you are truly struggling to complete the U.S. Evidence Chart, then attempt to fill a second chart using your ancestor’s sibling. Create a third using another sibling or cousin, as needed, to capture as much information as you can to identify parents, places of residence and birth within their origin country. Without these critical answers in place, your international research will seem all the more daunting, especially if records are written in a foreign language.

How do I get beyond the United States with my research?

Once you identify the precise origin of your ancestor, your research will seamlessly move beyond America. To prepare for this move, complete the following International Evidence Chart, focusing on the information you’ve learned about your ancestor’s family. You may not have every piece of this information, but you should now have about 70%.

Perhaps the most important information you must locate is the precise town, city or commune. Each country is unique, but it can be incredibly difficult to navigate records unless you have identified the smallest locality of origin. Without this, you may spend fruitless hours searching for records in the wrong area. Save yourself time by not only targeting a precise location, but also identifying a group of people you can use in your searches. This group will allow you to research everyone’s records in the hopes of finding the answers to your genealogical question.

Speaking of genealogical questions, add new questions as you solve each one along your research path. For example, once you locate the birthplace of your ancestor, perhaps now it is time to identify his or her parents. Once you gather proof of their parents, then focus on their date of marriage. Your genealogical questions should remain fluid. The amount of information you gather will increase with every step you take, up the research ladder.

| International Evidence Chart | |

| Ancestor Name | Sibling 1’s Name |

| Birthdate | Sibling 1’s Birthdate and Place and Baptism |

| Birthplace | Sibling 2’s Name |

| Baptism Date and Place | Sibling 2’s Birthdate and Place and Baptism |

| Religion | Sibling 3’s Name |

| International Residence/s (as detailed as possible) | Sibling 3’s Birthdate and Place and Baptism |

| Father’s Name | Sibling 4’s Name |

| Father’s Birthplace | Sibling 4’s Birthdate and Place and Baptism |

| Father’s Residence | Sibling 5’s Name |

| Mother’s Maiden Name | Sibling 5’s Birthdate and Place and Baptism |

| Mother’s Birthplace | Sibling 6’s Name |

| Mother’s Residence | Sibling 6’s Birthdate and Place and Baptism |

| Parents’ Marriage Date and Place | Sibling 7’s Name |

| Additional Notes | Sibling 7’s Birthdate and Place and Baptism |

| Sibling 8’s Name | |

| Sibling 8’s Birthdate and Place and Baptism | |

How can I visualize my ancestor’s homeland?

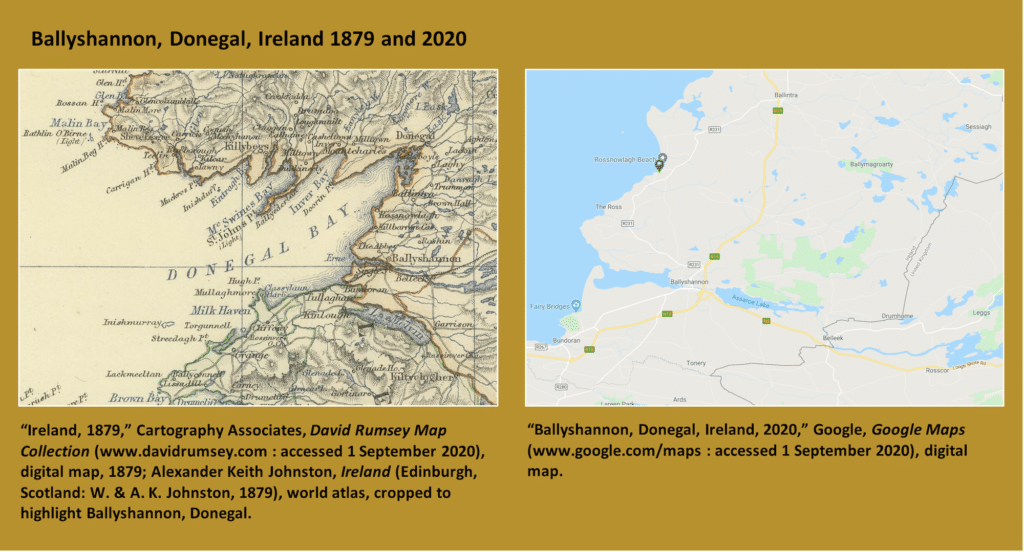

It’s important to understand the geographical origins of your ancestor if you’re going to be successful with your international genealogy research. You simply cannot fully understand what you cannot see. To visualize the old country, review maps specific to time and place, plus those specific to today. Start with Google Maps for present-day maps. Historical maps can be a bit trickier.

You may wish to complete a keyword search within your favorite search engine, such as “1870 map of Ballyshannon, Donegal, Ireland.” Your goal is to locate possible landholder maps. Those may not exist, but others do that will help you identify the names of places in and around your ancestor’s home. Through this exercise, you will locate churches, schools, streams, rivers, mountains, cities and other geographical and historical places of influence to your ancestor.

The Library of Congress website may hold the historical maps you need. You may also wish to visit a favorite online collection, the David Rumsey Map Collection. To get the best overview, look for maps from the timeframe when your ancestor lived there.

What if I cannot read the language of my ancestor’s country of origin?

Many genealogists, as they begin to explore international research, are met with what seems like an insurmountable barrier; a foreign language. Of course, you can hire a translator to assist your efforts or you can start by employing Google Translate. Simply type in the phrase you need to translate and your problem may be solved! You may still wish to hire that translator once you get deeper into records that include extensive, handwritten passages.

Always employ a cheat sheet for vocabulary critical to records you will encounter. Translate key genealogical keywords and add them to the chart below, to make record-reading a breeze. This little trick will save you so much time and energy. Index may be the most important word that you will ever need, as every advanced researcher knows that you employ the index to find the record.

| Key Vocabulary | ||||

| Index = | Birth = | Baptism = | Death = | Burial = |

| Marriage = | Husband = | Wife = | Son of = | Daughter of = |

What are some of the best practices when it comes to researching in the old country?

You can never read too much about the country you will be researching. Unearth everything you can about its history and culture. Universities are known for publishing histories in English as well as the original language. Shop in their online stores to find books for specific periods and places. Visit digital libraries such as JSTOR. There you will find journals, e-books and images that may add depth to your research.

Having a strong understanding of the historical timeline for your country will help you to navigate records left behind. It will assist your understanding of your ancestor’s decisions as a citizen of your international country, when planning his or her emigration.

Be aware of border changes, and changes to the governance of your country. Identify the impact of any military conflict or natural disaster that may have affected records from your country, not to mention your ancestor’s life there.

Explore cultural and societal patterns and norms. Many of your questions about your ancestors will be revealed through this type of education. There are books written on these subjects, generally penned by historians. These resources will offer insight into family and its place within society. This may be even more critical to your ancestral studies than their baptismal record could ever be.

As you move through your research, continually reformulate new genealogical questions. As you answer each question, new layers of questions should be formulated to guide your research. When you hit upon a wall of sorts, apply Reverse Genealogy. Do this by researching your hypothesized ancestors above the brick wall and attempt to close the gap by researching top-down instead of bottom-up. Be creative.

Where can I find research resources specific to my target country?

Seek out the experts first. Begin your quest by locating genealogical methodology books specific to your country. Borrow them or buy them, dependent on the extent of your use. These often include all available record groups and techniques to speed up your research process. It is critical to know which records groups are available to solve your genealogical question. Let others do this work for you.

Two invaluable go-to resources for international genealogy are both products of FamilySearch. The first is called Helpful International Websites. This resource points you in the right direction for every country imaginable. The second is a tad incomplete but is being added to every day. It’s called “How To” Guides for International Research. Always start at these two wiki pages to focus your brain as you begin to navigate international waters. They will keep you afloat. It is always worth the time to review Cyndi’s List, too.

Family History Daily also offers detailed information on researching a number of countries, as well as lists of free resources, in our online courses.

What types of records should I be looking for in my ancestor’s country of origin?

Depending on the country, international genealogy records may vary little, or a great deal, from record groups found in America. You will want to make a point of locating those record groups that are unique to your country, as well as those that are common to both. You will also want to make use of record substitutes that may fill gaps in your research that occur due to record loss.

For example, in Ireland there are dog license records, which may be unlike any others in the world. In addition, in Queensland, Australia, they have Toowoomba prison records available for online research. These are distinctive records and record groups, perhaps not available in other countries.

Break your research into two categories of records. Civil records, which would be created by the government, and Parochial records, which were created by the church. Knowing your ancestor’s religion is vital to finding records of this type. Without knowledge of their religious affiliation, you might miss out on one entire category. Remember to identify the range of years that the records were crafted to save yourself time and frustration.

Below in the International Record Groups chart, you will find many record types to choose from, as you begin your international research process.

| International Record Groups | ||||

| Agricultural Records | Baptism Records | Birth Records | Bordering Countries | Business Records |

| Cemetery Records | Census Records | Court Records | Death Records | Directories |

| Emigration Records | Estate Records | Genealogies | Land/Property Records | License Records |

| Maps | Marriage Records | Military Records | Newspaper Records | Occupational Records |

| Parish Registers | Published Works | Probate/Wills | School Records | Tax Records |

How do I know where to find records in my international country?

As you gingerly step into foreign research, you might feel as Alice did falling down the rabbit hole into Wonderland. It can be disorienting, to say the least. When lost, always seek out the experts. Review your books on international genealogy to identify archives, libraries, historical museums, and courthouses that hold the specific records that you seek. These repositories vary greatly from town to town, city to city, province to province, and country to country. Once you find them within your country, access their finding aids.

For example, when looking for records in England, visit the National Archives at Kew’s website. Their website will actually teach you how to find records held within. Use keyword searches, surname searches, and place name searches. Remember to identify what is available for specific time frames. Do not waste time looking for records where no records exist.

When researching parochial records, it can be daunting to find the correct church. Correlate information from your maps with records to pinpoint parishes. Learn the rules that govern which church your ancestor would attend, based on location. Be aware of privacy laws, and a denomination’s mandate on access to their records. Parochial records may not be considered open to public review.

Best practices for international genealogical research require you to first exhaust your research in America. Once armed with a specific locale, your research can move back into the old country. Identify record groups that will solve your genealogical questions. Support your efforts with expert strategies and methodology. The more you know, the more fruitful your international genealogy research will be.

Now that you have some basics down, it’s time to get started! Check out the international and immigration research sections on Family History Daily for more help or take a course to guide you.

Related Article: Why Getting to Know an Ancestor’s Location Can Be a Research Game Changer

By Bridget M. Sunderlin, CG®. Bridget practices in Maryland. She is the owner of Be Rooted Genealogy, where she specializes in Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York, Ireland, and Scotland research.

Image at Top: “Immigrants just arrived, awaiting examination, Ellis Island, New York harbor,” bet. 1870 and 1920. Library of Congress.

PLEASE, provide much needed contrast between the paper color and the ink: need bolder color on ink. Thank you.

I am so glad I stumbled on this guide. I took notes and I can’t wait to get started. I hope I can connect my grandfather to his home land. He came to America in 1920 from Norway I have found which ship he came on. I am so excited. Thank u for sharing this guide with us.

I have a Brick wall at my paternal – well, my Paternal Grandmother’s paternal Grandparents – Swedish immigrants. Sometimes the practice of “John’s son” becoming Johnson is consistent, but I’ve seen siblings who just stick to one family name.

Unfortunately, there are a lot of John Andersons who came from Sweden to the States at the same time, and there is an almost duplicate family who lived in Illinois, while “my” people lived always in Kansas. I still hope someone can help sort it.

This is an excellent website. Thank you, I don’t even remember how I ended up here 🙂 I’ve been reading for hours!