When I was a kid I read a story about the origins of surnames. It explained that long ago, last names ending in “son” originated because a boy was someone’s son, so “Jacobson” meant “son of Jacob” or “Johnson” meant “son of John.”

The story also said that people could be named by what they did for a living, like “Cook,” “Farmer,” or “Fisher.” I can’t remember where I read this, but it stuck with me — probably because my last name “Bryant” didn’t fit either of these naming conventions and I wanted to know where it came from.

Today, that lesson still intrigues me. Surnames are a critical piece of our genealogical research, and learning where a surname originated — geographically and etymologically — can not only enhance our research but add another chapter to our family history stories.

What is a surname?

A surname, sometimes known as a last name or family name, is a name that is passed down from one generation to the next and is typically shared by members of a family. They can be derived from a variety of sources, including a person’s occupation, location, nickname, or even their physical characteristics.

It turns out that the story I read as a child wasn’t too far off base when it comes to the early origins of surnames in some areas of the world. Many of them were indeed based on occupations and paternity, in addition to other characteristics.

Surnames, as a practice, came into being in England, for instance, after the Norman Conquest of 1066, and continued to evolve throughout the following centuries. The need for surnames stemmed from a growing population and the problem with differentiating multiple people with the same names.

Inevitably, people would add descriptive words when referring to someone with a common name, such as “John the tailor,” or “Joseph, son of James.” These examples would evolve into the names “John Taylor” and “Joseph Jameson.” In Scotland, the prefix “Mac” indicated paternity, such as in the name “MacDonald” or “son of Donald.”

Ancestry.com and other sources cite several major influences on the creation of English surnames. In addition to occupation and father’s name, surnames were also derived from geography and descriptive characteristics.

Geographical names could stem from the name of an English estate (such as the Royal family’s invented name of “Windsor”), the place name of a town or village where someone lived or worked (“London” or “Sutton”), or even a feature of the landscape (“Hill,” “Stone,” “Wood,” or “Field”). Descriptive names like “Young,” “White,” “Short,” or “Lightfoot” most likely described the first person to use the surname.

Of course, you have to look at the meaning of the name in the particular country where it originated. For example, several sources tell me that “Bryant” originated from “brigh,” which meant “strong.” Others tell me that it’s derived from “bre-” which means “hill.” “Brigh” was also the inspiration for the Irish given name Brian, as in Brian, the king of Ireland in 1002. Many Irish and Scottish surnames were derived from the names of legendary leaders or the clans to which people belonged. “Douglas,” “Crawford,” and “Stewart” were all Scottish clans, while the name “Kilpatrick” means “follower of (Saint) Patrick.”

The thing to remember is that every single location and group around the world had, and has, its own unique surname practices – many of which have evolved dramatically over time. Patronymics and matronymics, the practice of naming a child after a father or mother, have been around for centuries, but in many places the unchanging last name, as we think of it now, is a relatively new idea. In other locations, family names have been used for countless generations.

Whether your ancestors come from the Netherlands, Finland, France, China or Brazil (for instance) does matter – so make sure you take the time to understand the history of naming practices in the geographical areas where your family lived. Remember also that religion and other factors had a big impact in naming practices in some areas.

Look for genealogical societies online that are focused on the country or region where your ancestors’ lived for the most accurate help. Wikipedia can also be a good source of details on this topic. Trying searching for the name of a country and “surnames” to get a history of that area.

The Internet is filled with sites offering to provide the true meaning of your specific surname, but beware of those that also want to sell you an expensive surname plaque or coat of arms. For the most reliable information on the etymology of your surname, stick to reputable sites like Ancestry.com’s Last Name Meaning Search, Forebears.io, or Surname Database. You might also consult Google Books or your local library for printed surname dictionaries, but pay close attention to the authority and reliability of the author.

See a list of common US last names here, as well as a list of rare ones.

Common types of surnames:

- Patronymic

- Matronymic

- Occupational

- Geographical

- Descriptive

Patronymic Surnames

Patronymic surnames are a type of surname that is derived from the name of a person’s father. They are common in many cultures around the world, including those where family names are inherited through the male line, such as in Russia, where people’s last names are often formed by adding “-ovich” or “-evich” for a son, or “-ovna” or “-evna” for a daughter, to the father’s first name.

For example, if a man named Ivan has a father named Peter, his full name would be Ivan Petrovich. If Ivan had a daughter named Maria, her full name would be Maria Ivanovna. Patronymic surnames can provide a sense of a person’s family history and lineage through the names of their fathers.

Matronymic Surnames

Matronymic surnames are a type of surname that is derived from the name of a person’s mother rather than their father. They are commonly used in cultures where family names are formed in this way, such as in Iceland, where people’s last names are made up of their father’s first name with the suffix “-son” or “-dóttir” added depending on their gender.

For example, if a man named Jón has a mother named Sigrid, his full name would be Jón Sigridarson. If Jón had a daughter named Anna, her full name would be Anna Jónsdóttir. Matronymic surnames can provide a glimpse into a person’s family history and lineage through the names of their mothers.

Occupational Surnames

Occupational surnames are a type of surname that derives from the occupation or trade of an individual or their ancestor. These surnames originated during the Middle Ages when surnames became more common and people began to identify themselves with a particular occupation.

Examples of occupational surnames include Baker, Smith, Carpenter, Fisher, Cooper, and Taylor. These surnames indicate that the person or their ancestor was involved in the respective occupations. For instance, someone with the surname Baker may have been a baker by trade, while someone with the surname Smith may have been a blacksmith.

Geographical Surnames

Geographical surnames usually come from a specific region or location within a country. They can also be related to a geological feature near where your ancestors lived, such as a valley. Examples of geographical surnames include Hill, Wood, Field, Rivers, and Forest – as well as translations of these types of features in the language of your ancestor’s country of origin.

Descriptive Surnames

Descriptive surnames are a type of surname that describes a physical characteristic, personality trait, or other distinctive feature of an individual or their ancestor. These surnames often originated during the Middle Ages when people began to use descriptive terms to distinguish between individuals with the same given name.

Examples of descriptive surnames include Brown, Black, White, Short, Long, and Good. These surnames may indicate physical characteristics, such as hair color or height, or personality traits, such as kindness or honesty.

Using Surnames in Your Research

While learning what your name means is certainly interesting, it could be difficult to trace your surname back to the individual with whom it originated (I immediately question the research of folks who say they’ve traced their ancestry back to the ninth century). But although you may never know which of your “Armstrong” great-grandfathers had muscular biceps or which “Cooper” worked as a barrel-maker, there are multiple ways to use surnames in your genealogical research.

Geographical distribution

Studying the geographical distribution of your surname, or creating a surname map, can help you to advance your research using where the majority of people with your surname lived at any given time. Surname maps are derived from census records, voting lists, and even city directories; this means, of course, that most mapping tools will only provide data back to the time when record-keeping originated. However, this process can still be worthwhile to your research.

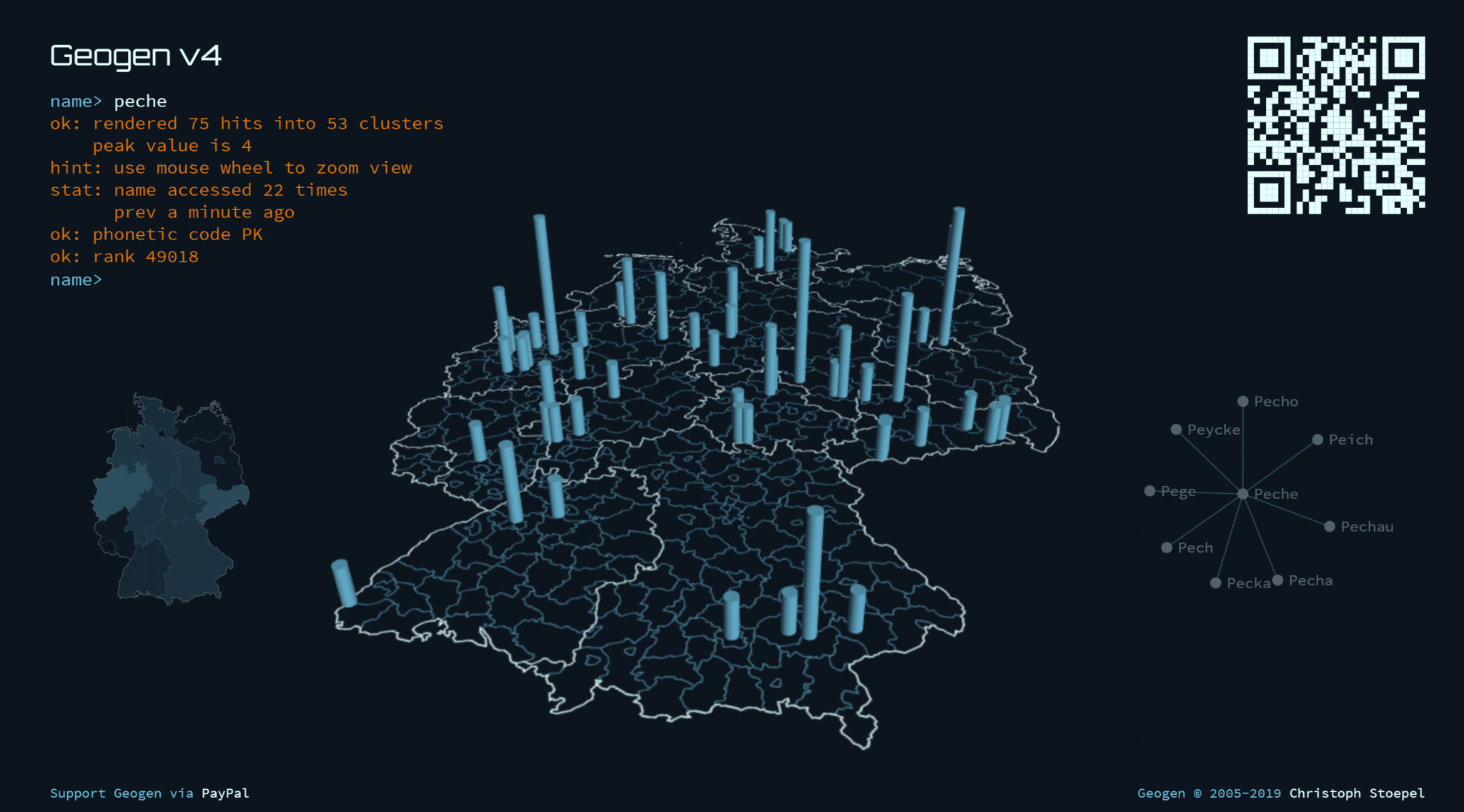

Ancestry’s surname search and Forebears both offer surname distribution mapping, and the wiki sites for FamilySearch and the International Society of Genetic Genealogy provide comprehensive lists of country-specific online surname mapping tools. I tried the German mapping site, GeoGenic Germany, to study my “Peck/Peche” surname, resulting in this intriguing graphic:

After comparing the GeoGenic image to a map of Germany, I see that the highest concentration of the surname “Peche” (the tallest pole on the graphic) is around the city of Berlin. Indeed, many of my Peche ancestors were from the easternmost area of the country, which is now part of Poland.

Surname studies

Participating in a surname study can seem daunting due to the sheer number of folks you’ll encounter within your group, but the benefits definitely outweigh the risks. According to The Surname Society, an online organization started in 2014 to support the study of surnames, studying a particular surname in-depth combines “various approaches including collection of documentary event data, DNA results, research into the origin of the surname and its distribution and how the name has changed over time.”

Often referred to as “one-name studies,” surname studies leverage the power of crowdsourcing and collaboration to provide as much information as possible on early ancestors bearing your surname. You’ll also learn more from this group about the variations on your surname, which will help you as you plow through census records written by what can often seem to be the worst spellers in the world. You may have never see your “Threet” surname spelled “Threewit,” but perhaps another member of your study has.

DNA studies associate with surnames are also chock-full of potential information, particularly scientifically-based genetic details that can prove or disprove a family connection. Although most DNA surname projects require you to upload Y-DNA results from a male descendant who carries the surname, some accept mtDNA (maternal line) or autosomal (combined) results. FamilyTreeDNA and Cyndi’s List offer listings of tens of thousands of DNA surname projects. Most are volunteer-run and participation is free.

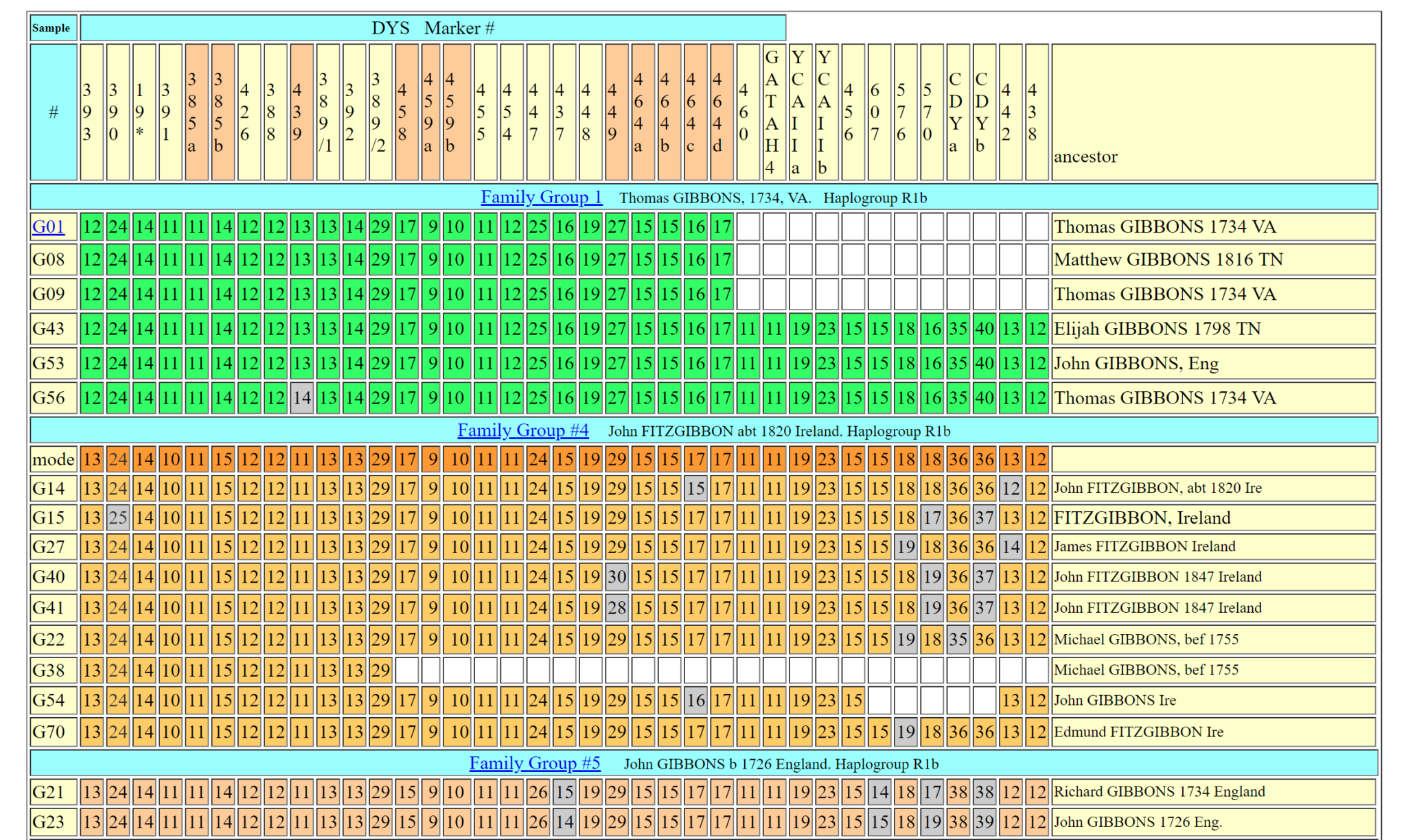

In 2011, I submitted my uncle’s Y-DNA results to the Gibbons surname project. This project’s objectives included “finding new relationship for those who have reached a dead end in their genealogy research” and “developing a database that combines DNA results with traditional genealogy research.” The administrator compared my uncle’s DNA to the DNA other Gibbons men had submitted, and found that we belong in Family Group #4, along with eight other participants (he’s number G54 in the diagram below).

Each of us also submitted the name of our earliest Gibbons ancestor according to our paper documentation; my paper trail ends around 1820. The group’s administrator believes that the common Gibbons ancestor for our family group predates the research we’ve all submitted.

Message boards and mailing lists

Oldies, but goodies, message boards and mailing lists can be goldmines of surname-related information. Similarly to a surname study, participants in surname-titled boards and lists will post what they know about their ancestor(s) of the same name, usually including some biographical and geographical information and their particular brick wall. As is the case with most family historians, folks will usually respond with their own stories or research findings.

Rootsweb still offers a listing of surname mailing lists, which require registration in order to start receiving emails when a new post appears. Many of these lists are marked as “inactive,” but you can still review previous posts.

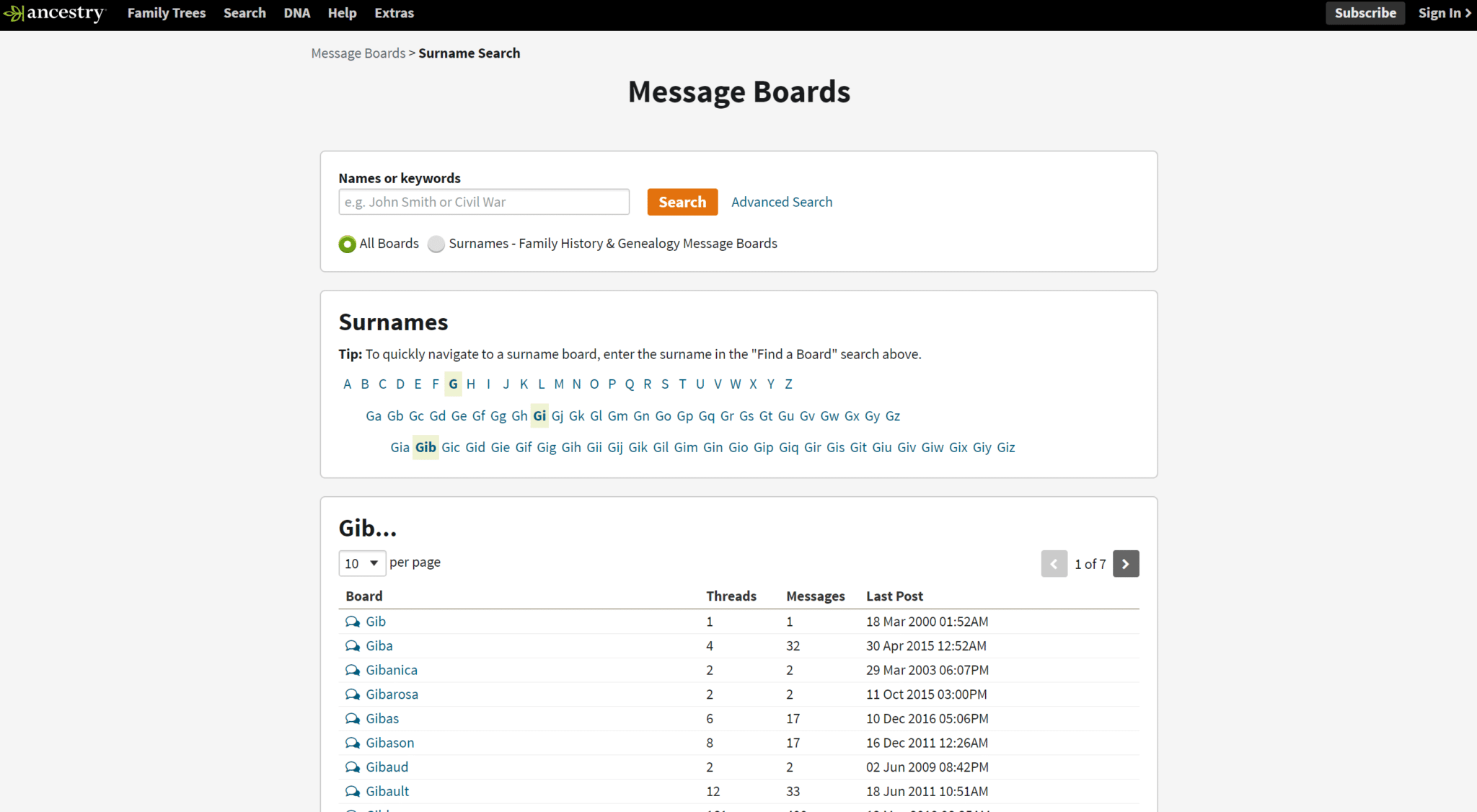

For surname message boards, nothing beats those hosted by Ancestry.com. First of all, they’re comprehensive, with hundreds of thousands of boards and millions of posts. Ancestry makes it easy to find a board with your surname or its many variations.

Best of all, they’re free. You can browse Ancestry’s message board posts without registering, but to post or respond to a post, (free) registration is required. It’s also worthwhile to explore the archived surname posts on GenForum, the message boards which were once hosted by Genealogy.com. Ancestry bought and deactivated Genealogy.com in 2014, but the message boards are still viewable and could add to your surname research.

Other surname applications

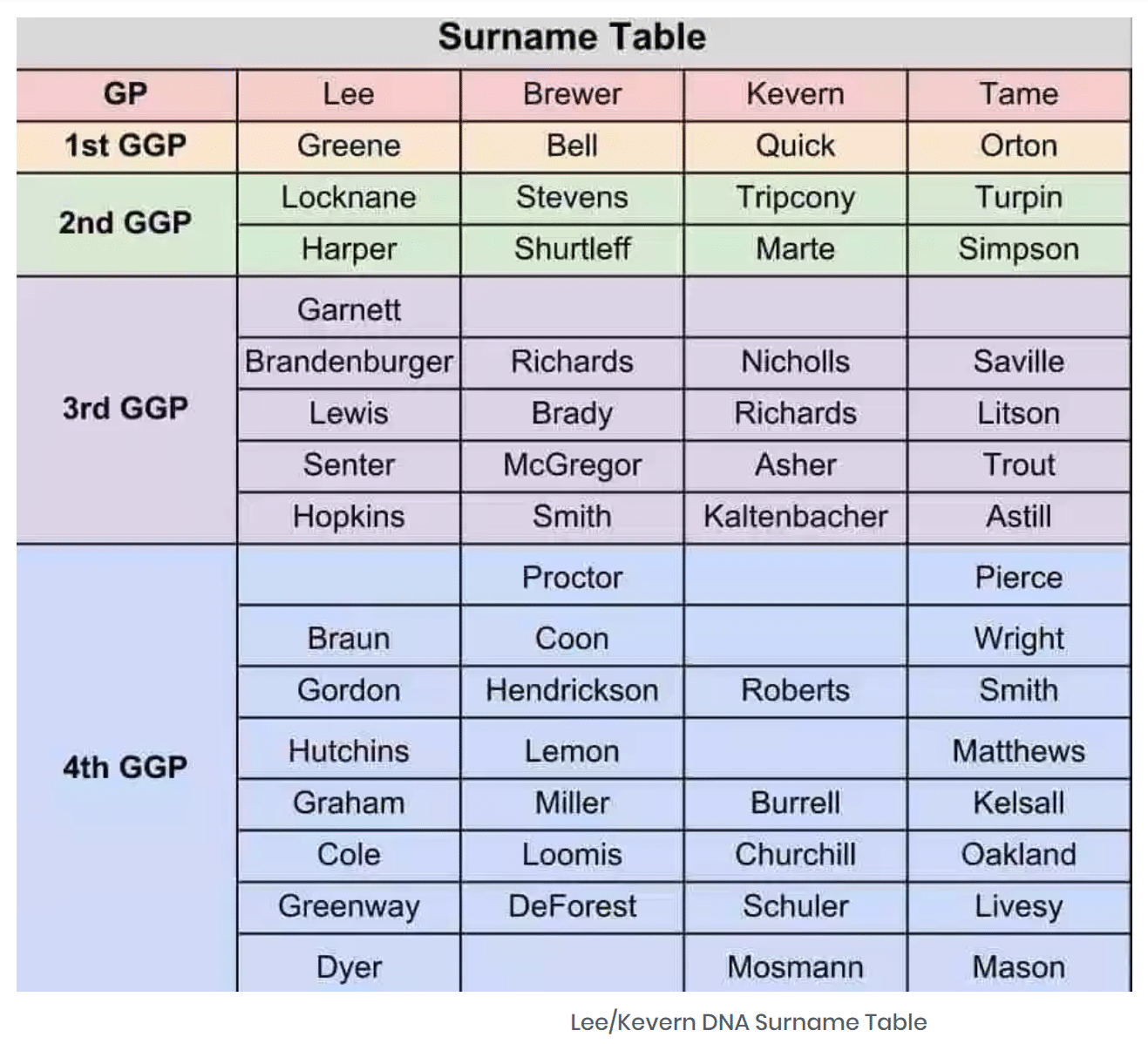

In researching how surnames can help your genealogical research, I came across a simple tool that makes so much sense, I’m not sure why everyone’s not doing it. A surname table not only gives you a cheat-sheet for your family tree’s surnames (which multiply with every generation), but also gives you a visual for where those surnames lie in the tree, and which ones you’re missing. Here’s an example I found on Devin Noel Lee’s Family History Fanatics blog:

Mine (and perhaps yours?) probably wouldn’t be nearly as comprehensive as this one, but you get the idea. How nice would it be to have this handy reference taped to the inside of your genealogy research notebook, or added to your email signature when composing family history emails?

As genealogists, we recognize that our surnames may have morphed over time or been completely changed due to immigration or other reasons that might remain unknown to us. Understanding your surnames — in all forms — is still integral to building a comprehensive picture of your family history. Consider this statement from William Arthur, father of President Chester A. Arthur and author of “An Essay on the Origin and Import of Family Names:’

“But shall we wonder when we consider that names have been taken and bestowed from every imaginable incident and occurrence unknown to us, and that many of them have been so corrupted in process of time, that we can not trace their originals. All names must have been originally significant.”

You might also like to read:

- One-Name Studies: Why Study Just One Surname?

- Could You Have Royalty Hiding in Your Family Tree? Check This List of Surnames

By Patricia Hartley. For nearly 30 years Patricia has researched and written about the ancestry and/or descendancy of her personal family lines, those of her extended family and friends, and of historical figures in her community. After earning a B.S. in Professional Writing and English and an M.A. in English from the University of North Alabama in Florence, Alabama, she completed an M.A. in Public Relations/Mass Communications from Kent State University.

It really helps to have a rare surname such as mine – Randrup. And my mother’s is not very common either (Bang – it’s pronounced like the English word “BUNK” but instead of the hard “K” it’s like a “Guh” sound that’s basically (sort of) silent. Sort of disappears in the back of your throat. Say BUNK tersly but drop the “K” sound. It’s a toughie! The Danes have AMAZING online Church Registry record databases – all free – but searching for a Danish surname such as Pedersen or Jensen woul d be a nightmare. There are currently over 300,000 Jensens (yen-sen not gen-sen) in Denmark but only 468 Randrups and a little over 3,000 Bangs.