We all know that we need to be careful when reading, using and recording information we find in the census. Whether it’s the US federal census, a state or local census, or a population register for another country, these records are notoriously inaccurate. Ages, name spellings, locations of birth, occupations – everything needs to be questioned and sourced.

However, because of their predictability and wide coverage, census records remain an invaluable tool for family historians. And these records can contain some very valuable and exciting information about our ancestors.

But there is some information that may change the way you look at census records in general -information that may even make you question some of the census data you’ve collected in the past. We’re talking about the Instructions to Enumerators held by the US Census Bureau, which are fully available online.

Why Understanding the Instructions for Enumerators of the U.S. Census is Important to Your Research

At first glance Instructions to Enumerators sounds pretty benign — it certainly doesn’t sound like it should be shaking any foundations. But it turns out that these documents provide some very surprising insights into the data recorded in the US census.

The Instructions to Enumerators specified for census takers what information was to be collected for each census year, how to properly collect that information, what data should be questioned and what data should be excluded.

The instructions put much of the information that we often take at face value into a whole new light, providing a context for how that information should be read, understood and used.

Let’s look at a few examples from the 1930 instructions provided to enumerators.

Instruction on Occupations in the Census

Turns out that we need to be more careful than we thought when assuming that our ancestor was actively employed in an occupation that was listed for them in the census.

Section 189 of the 1930 Instructions for Enumerators states:

…persons out of employment when visited by the enumerator may state that they have no occupation, when the fact is that they usually have an occupation but happen to be idle or unemployed at the time of the visit. In such cases the return should be the occupation followed when the person is employed or the occupation in which last regularly employed, and the fact that the person was not at work should be recorded in column 28.

33 Billion Genealogy Records Are Free for 2 WeeksGet two full weeks of free access to more than 33 billion genealogy records right now. You’ll also gain access to the MyHeritage discoveries tool that locates information about your ancestors automatically when you upload or create a tree. Find your ancestors now.

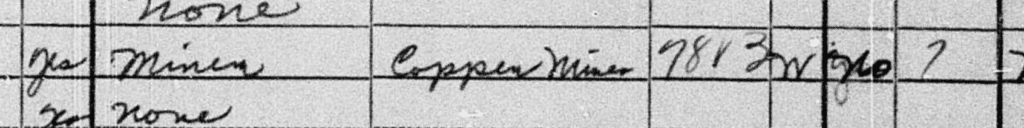

Here’s what this looks like in a 1930 census record. Below we have James Merryman, who is 40 years old. He is listed a “miner” in the “copper mine.” A cursory examination of the record would lead us to add this occupation to our files for the year 1930.

But a closer look reveals that James is not currently employed in this capacity. See the “no’?

Of course, we don’t need the Instructions to tell us this information, it is right in front of us. But understanding how occupations were recorded does provide insights that we did not have before. We now know that the occupation listed for James was “the occupation in which [he was] last regularly employed.”

Rather than assuming that James held this occupation recently, we can now make the determination that he may have been working at this job just weeks before or that it could have been years since James worked in this capacity.

In fact, section 250 of this same document states:

Persons will be found who have been long unemployed because of change in industry, the introduction of machines, or the decline of production in certain lines. If able and willing to do work of any kind, these persons should be returned as usually working at a gainful occupation, without regard to the length of the period of idleness, provided they still expect to find employment and resume work.

If he was not a miner in 1930, when was he last a miner? How long did he hold this occupation? We just don’t know.

Given this new information, we have to wonder if the occupation is terribly relevant in 1930. If we want to add it to our tree, should we now place a date such as bef. 1930 along with it? This would certainly be more accurate.

Some of you might have noticed the number 7 in the screen clip above. This number relates to additional information that was recorded in the Unemployment Schedule. This schedule could have given us the clues we needed to understand his current and past employment – and this is no doubt what was intended by the Census Bureau – but, unfortunately, these records no longer exist.

Instructions for the 1930 census go on to tell us that only one occupation is recorded per person, even when a person may have held multiple positions (section 190). Certainly, this was done out of necessity, but we can’t help wondering what information may have been cut.

Information about women’s occupations in this same year also leads us to ask some questions we may not have asked before. Several sections of the instructions (for various census years) relate particularly to women’s work. The bureau took the time to define it as important and is careful to make it clear that the work should be recorded.

Where a woman not only looks after her own home but also has employment outside or does work at home for which she receives payment, the outside work or gainful employment should ordinarily be reported as her occupation, unless this takes only a very small fraction of the woman’s time. (section 196, 1930)

And yet, some work done by woman was not recorded, despite the information above (as well as additional instructions in the same year) that state that any work that exceeds one day per week should be listed (section 187). As shown in the example below, women who contribute to the farm labor of their own farm (or another’s?) should only be listed as farm laborers under very certain circumstances.

Section 197 states:

A woman who works only occasionally, or only a short time each day at outdoor farm or garden work, or in the dairy, or in caring for livestock or poultry should not be returned as a farm laborer; but for a woman who works regularly and most of the time at such work, the return in column 25 should be farm laborer. Of course, a woman who herself operates or runs a farm or plantation should be reported as a farmer and not as a farm laborer. (bolding is our own)

This is very interesting. Why must a woman spend “most of the time at such work” to be given such an occupation, when a man was listed as such if he carried this occupation only one day per week, or even if he carried it in the past but is no longer active at it?

And this is not the only place where it is suggested that women’s work should be excluded if it did not comprise a significant portion of her time. It does seem that while the census bureau at the time was concerned about recording women’s occupations correctly, some policies may have led them to provide less than truthful results by encouraging the mention of paid employment for men while restricting it for women.

Is it time to start doing some serious reexamination of our female ancestors’ lack of “gainful employment” in the census? Were more women in our tree undertaking paid work than we previously thought? Could more of our female ancestors have contributed to work around the home that was traditionally considered men’s work and added to the monetary resources of the family?

Instructions on Veterans in the Census

The instructions also remind us that we need to be very careful when making assumptions about the meaning of seemingly straightforward entries – such as a listing for “veteran.” For instance, the 1930 instructions state that the enumerator should list someone as a veteran under these specific conditions only.

“Yes” for a man who is an ex-service veteran of the United States forces (Army, Navy, or Marine Corps) mobilized for any war or expedition, and “No” for a man who is not an ex-service veteran. (section 237)

The instructions go on to clarify that men should only be considered veterans “who were in the Army, Navy, or Marine Corps of the United States during the period of any United States war, even though they may not have gotten beyond the training camp. A World War veteran would have been in the service between 1917 and 1921; a Spanish American War veteran, between 1898 and 1902; a Civil War veteran, between 1861 and 1866.” (section 239)

So a man who served in the armed forces may be excluded if he was not in active service during a war or was not part of a recognized expedition, but may have been included if he served during a war, even if he never made it through training.

These same instructions are also clear that “No entry is to be made in this column for males under 21 years of age nor for females of any age whatever.” (section 237)

Whether these restrictions are justified is something for discussion – but the most important element here is that with this information we have a much more accurate picture of the data we are collecting.

Without this information we might be tempted to draw our own conclusions about our ancestor’s military service. With this information we can gather a deeper understanding of why someone may, or may not, have been listed with veteran status.

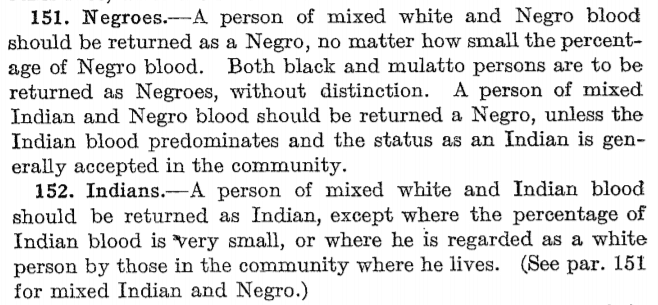

Instructions on Ethnicity in the Census

The instructions can also tell us some very interesting information about how one’s “color or race” was decided. Reading through these sections in several census years raised quite a few questions, and definitely makes us want to go back and take a second look at some records. Here is a section from 1930.

Instructions on Age in the Census

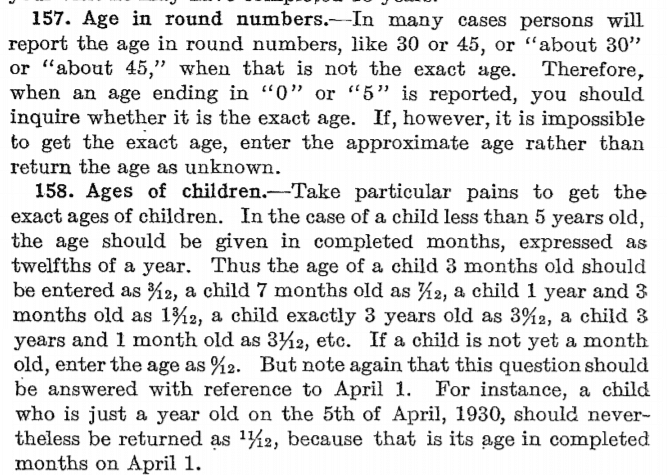

The instructions can also help us understand our ancestors’ ages properly. The 1930 instructions define exactly how an age should be recorded, and knowing this information could easily change estimated birth years for many people in your tree.

This question calls for the age in completed years at last birthday. Remember however, that the age question, like all other questions on the schedule, relates to April 1, 1930. Thus a person whose exact age on April 1, the census day, is 17 years, 11 months, and 20 days should be returned simply as 17, because that is his age at his last birthday prior to April 1, even though at the time of your visit he may have completed 18 years. (section 156)

Each census year had its own date by which ages were recorded, and it is important to know each one.

Further examination of the age section shows us how much care was actually taken in an effort to record the correct age of a person. Although we know that ages are one of the most unreliable details in any census, it is clear that enumerators were expected to come back with as accurate information as was possible to gather.

These are, of course, just a few examples of the fascinating and revealing information that the Instructions for Enumerators can provide you in your research. While we don’t expect you to read every page of every instruction document, we do suggest that you take the time to read those sections that pertain to pertinent information in your tree — especially when you are unable to find additional sources for that information.

These documents can also be incredibly helpful if a piece of information in a census is confusing, seems misplaced, or is missing. The instructions for that year might provide the clues you need to make sense of that data.

Below is a list of instructions for all available years for 1790 through 1950 – it excludes 1840 where no information is currently available. Earlier instructions were not nearly as detailed as later ones however. Additional information can be found here. Although we have only explored the US Federal Census in this article, you may consider finding and reading the instructions for any other census/population registers you have used as well.

For even more detailed help using the census for genealogy research, register for our online courses.

You may also enjoy these articles:

- A Quick Guide to the U.S. Census for Genealogy

- The ‘Secret’ Details in the 1940 Census You May Be Missing

- Thousands of 1890 Census Records DO Still Exist: Here’s How to Find Them for Free

- What Really Happened to the 1890 Census?

By Melanie Mayo, Family History Daily Editor

Very true Joanna. For some of my Family they are missing more then a couple of Years. I found they were Share Croppers and they were missed in more then one census. I do see a lot of information that is Valuable to the research.

Interesting, however other questions with the Census that I have run into and feel is also important. We should consider the timeframe of each report. If it’s January in Minnesota and you knock on a door to gather information are you going to be welcomed or rushed to get the data? If it’s May in Iowa and you hold up a Farmer from working is the data going to be quick so he can return to working the field?

Like all research we should gather as much information as we can, even if that information is from a document that has been reprinted more then once. Returning to the point of the original document is great when we can go. Helping others to gather information can also work out great. I started my Tree from a book about one branch of my family. This book was Published when the Databases and aids when not around and information was gathered by phone, letters, and sometimes Visits. It is not perfect as I have discovered but it was a great start.

I find the age calculations in the 1900 census strange. Everybody seems to be off by a year. Why?

A lot of persons left out of census, their housing so remote, were just missed. I have found this to be true in my own research. And i personally knew they were there. My own family. Census is helpful, but not always accurate. Lot of persons didnt know how to spell their names or even know their accurate birth date. Had this happen when i got a birth certificate. 3 months different.

I had already noticed the discrepencies in public records. There appears to be no basic educational requirements for recording for posterity the details of our lives. I have many doubts about Census Records after finding that much information was obtained from the children at the house!!!

In 1940 I am sure an enumerator in Tuscaloosa, Alabama had to be drunk, lazy, or incompetent.

My grandmother (Lunsford) was living in a house owned and occupied by her brother (Read). Their father (Read)

had died there in 1937. My mother (Atkins, nee Lunsford) had moved out in 1930 and was living in Gadsden, AL)

Nonetheless, my late great-gf Read was listed as head of household, My GM Lunsford was listed as a Read, and my mother, her daughter, was also listed as a Read. So, my mother was listed both in Tuscaloosa and Gadsden.

I know my Unruh’s were in Porter County, IN in 1850, 1860 and 1870.

There was John Sr. Naoma, Joseph. Elizabeth, William B.

Why did they not show up whith Search?

Perhaps you do not have that information?

Thank you,

Ann Archer

Since I already read the Enumerator instructions before looking at each census, I don’t think that any of my data will change…

Sounds more like clickbait than useful hints…

read: “excerpt”