Over the course of family history research, many people around the world will find that their ancestry leads back to the British Isles in one way or another. If you are a part of this group, congratulations: you’re about to step into some of the world’s oldest and richest archives. In this guide we introduce you to the key sites, sources and strategies to help you find these ancestors.

While we have made every effort to include links to free resources in this article, we have also linked to paid resources that can help you in your UK genealogy research. Because we use them ourselves, we have partnered with some of these sites to share information about their services with you and may earn a fee if you choose to take advantage of them.

The Genealogy Research Landscape in the British Isles

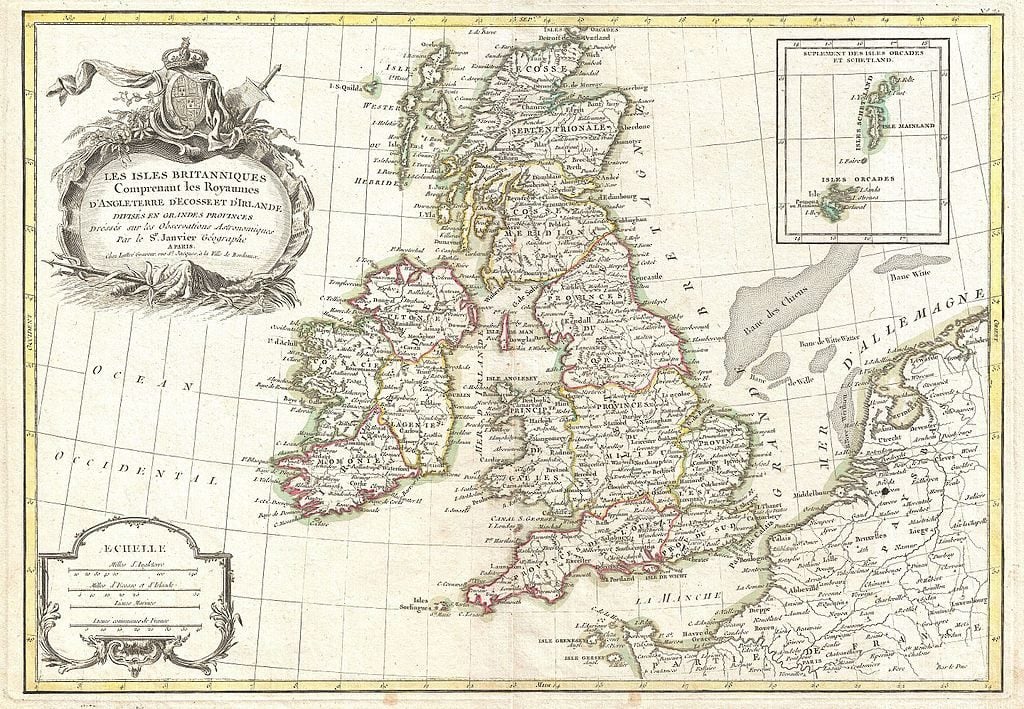

The geographical entity known as the British Isles comprises several distinct countries and jurisdictions, each with its own records and archives. You’ll need to know roughly where your ancestors lived in order to be sure you’re looking in the right place. So, to get our bearings, we’ll start with a brief tour of the main archives and websites.

Key Resources for Genealogy Research in England and Wales

England was and is the largest of the four nations that make up the British Isles in terms of both area and population. Historically, it was divided into 39 counties that had existed since medieval times.

Lying to the west, Wales was brought fully under English law by Henry VIII in the early 1500s. Since then, England and Wales have shared a common legal system and hence tend to have similar records. Although most are written in English, you may also come across Latin (pre-1650, especially in legal documents) and Welsh (which continued to be used in some parts of Wales).

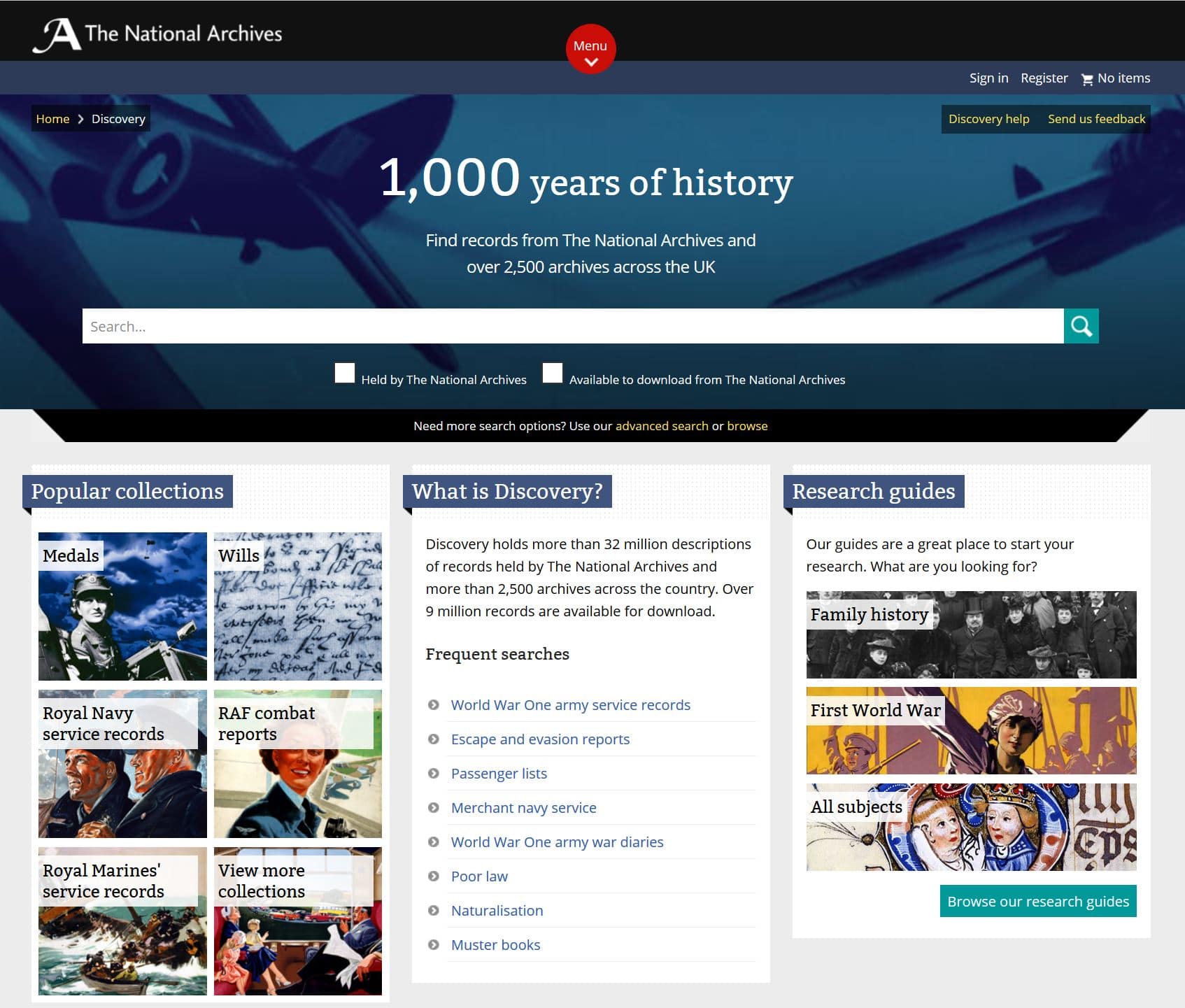

The National Archives (often referred to simply as ‘TNA’) at Kew, south-west of London, holds over a thousand years of English records. Its collections can be searched via the Discovery Catalogue: this covers not only the TNA’s own holdings but also those of other English and Welsh archives.

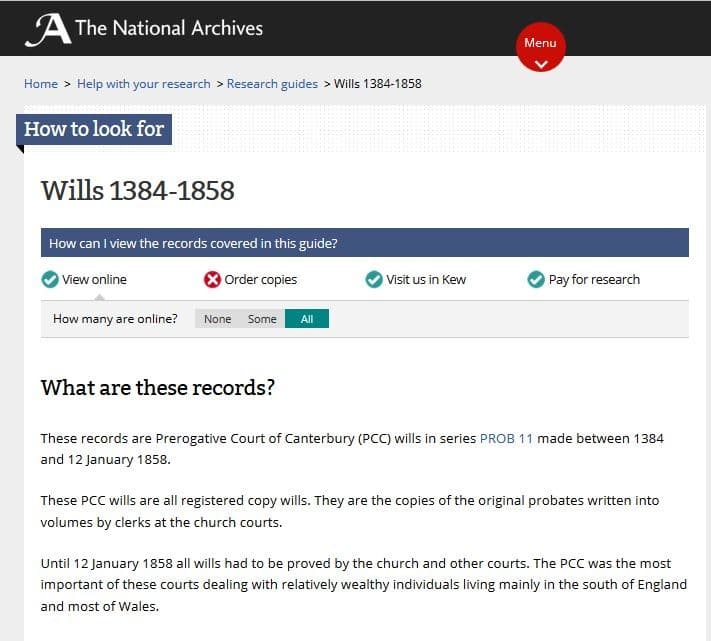

Many of the most important collections are available online, some free of charge and others on either a pay-per-view basis or through commercial providers. The TNA website has an extensive series of research guides offering help and advice on key topics.

In Wales, the main repository is the National Library of Wales, which houses many important sources including church and legal records. The online catalog at Archives Wales provides a gateway into other Welsh repositories.

Many English and Welsh record sets of interest to the family historian are held at a local level in county or city archives (often referred to as county record offices or ‘CROs’). Of particular note are the London Metropolitan Archives (LMA) and Guildhall Library which house rich collections for London.

Key Research Resources for Scotland

Scotland was an independent country for hundreds of years and remained so even after a joint monarchy with England & Wales was established in 1603. The two only became united politically – as ‘Great Britain’ – with a single parliament, in 1707. Scotland retained its separate legal system and religious identity and this remains the case today. Hence, the record sets used by family historians can look substantially different to those for England and Wales.

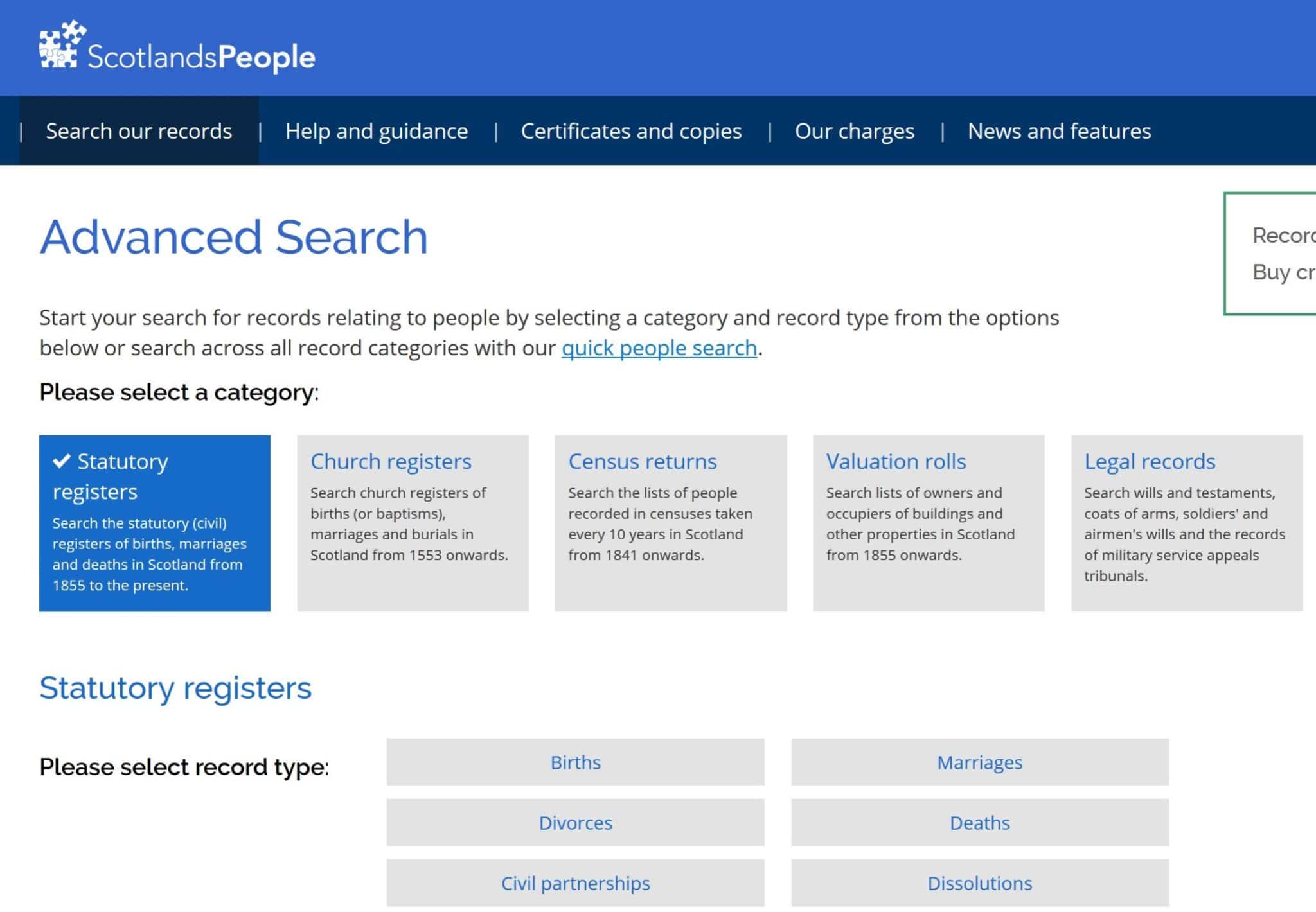

The main archive is National Records of Scotland in Edinburgh, which runs the excellent ScotlandsPeople website. Here you’ll find vital records, church registers, census returns and much more, all of which are free to search (with a free account) – original records are accessible on a pay-per-view basis. Also of note is the Scottish Archive Network, an electronic catalog to the holdings of more than 50 Scottish archives.

Key Genealogy Resources for Ireland and Northern Ireland

The island of Ireland was ruled by the British Crown for centuries and became part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801. After a prolonged campaign for Irish Home Rule that became increasingly violent, partition was agreed on in 1921 between the Irish Free State in the south, which became an independent country, and Northern Ireland, which remained part of the UK.

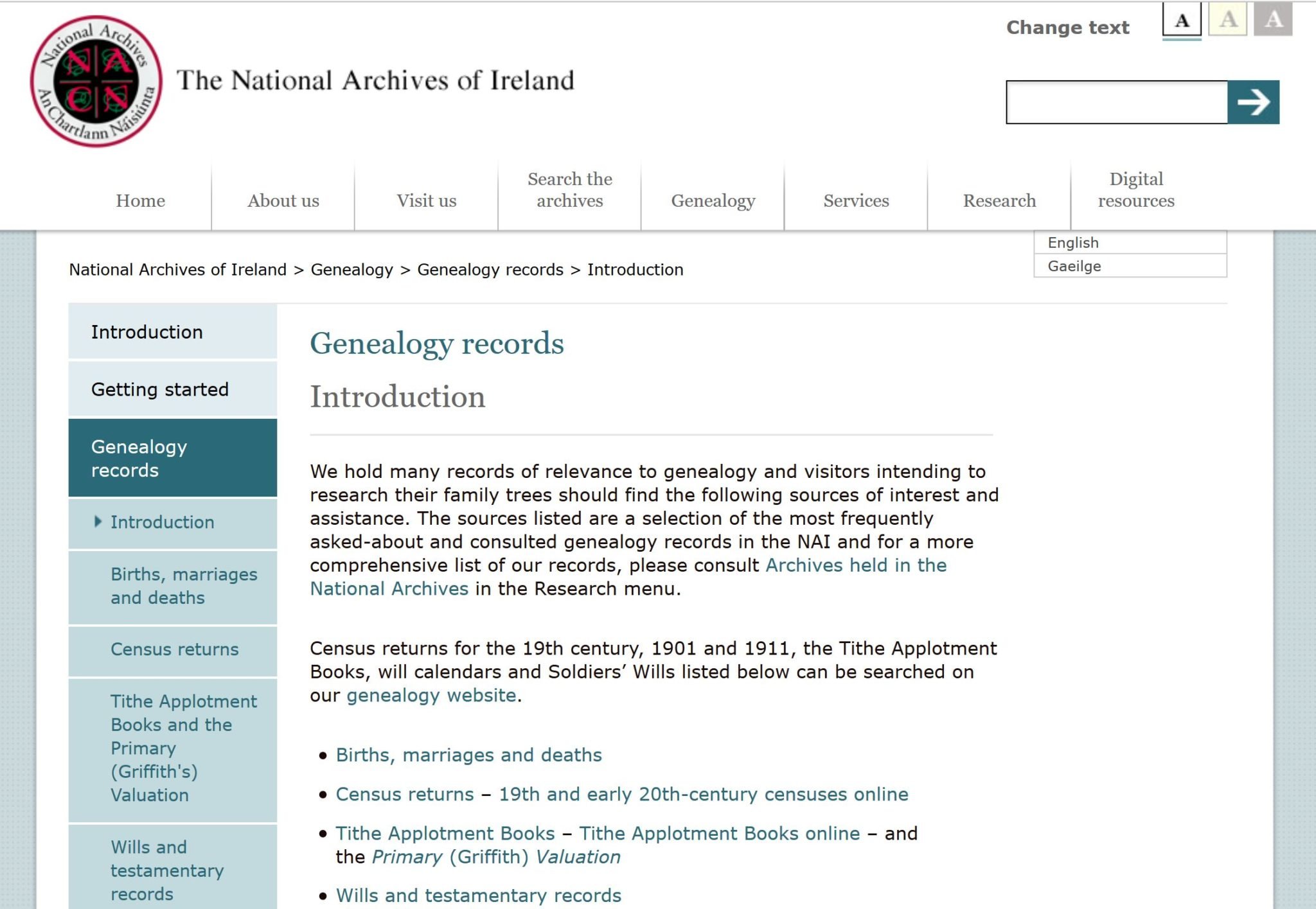

The Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) is the official archive for Northern Ireland. Its website includes an eCatalogue, as well as online access to key record sets. For Ireland, the government-run website Irish Genealogy.ie. is dedicated to helping you search for your Irish family history and has beginner’s guides and useful links. The National Archives of Ireland, which holds census records, is another important site.

The Channel Islands, off the coast of France, and the Isle of Man, in the middle of the Irish Sea, are Crown Dependencies – a special status that means they are not formally part of the United Kingdom. Jersey and the Isle of Man each have small local archives. Key collections from these territories are on FamilySearch and other websites.

Essential Resources for Researching Your UK and Irish Ancestors Online

When it comes to researching online there is no shortage of websites to help you find your ancestors from the British Isles. The commercial sites Ancestry and FindMyPast both have rich collections of English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish records which are being expanded all of the time. You can find a complete list of Ancestry’s UK record collections here. FindMyPast has its roots in Britain and has many unique record sets that are not available elsewhere. Learn more about what they have to offer here.

On both sites, a ‘world’ or ‘all access’ subscription package may be necessary in order to access these collections from other territories. However, there are many free or low-cost alternatives, however, including FamilySearch and websites run by local family history societies within the area concerned.

The Society of Genealogists, based in London, is the UK’s oldest society dedicated to genealogy and family history. Its huge library contains thousands of unique records that you will not find anywhere else, some of which are available online to members. There is also an online bookshop and learning zone.

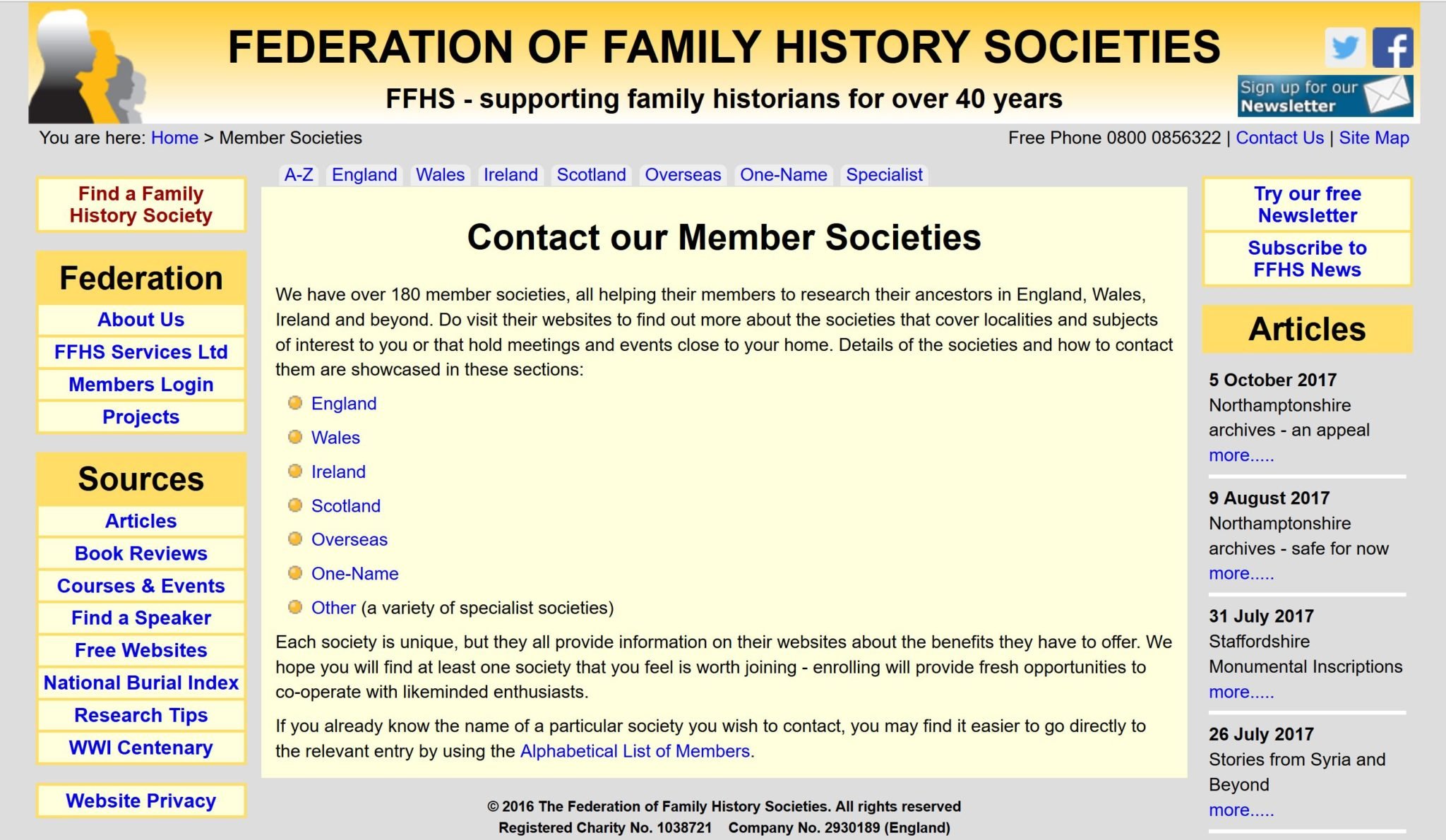

Family history societies (or ‘FHSs’) operate across the UK, bringing together people with an interest in a particular locality (generally at the county level). As well as organizing regular meetings, FHS volunteers painstakingly transcribe local records which are available to purchase or download through society websites.

The Federation of Family History Societies (FFHS) has links to over 180 member societies within England, Wales, and Ireland, as well as a sister organization covering societies in Scotland. Local (as opposed to family) history societies are also worth seeking out in order to get an insight into a particular locality.

Finally, when it comes to sketching out the landscape, GENUKI, GenGuide, and the well-known FamilySearch Wiki are all portals or reference sites offering useful guides and links on various aspects of British and Irish research.

The 1840 Threshold

The period around 1840 is a key reference point when it comes to researching ancestors in Britain. This saw the beginnings of a national system of civil registration of births, marriages, and deaths (started in 1837, initially in England and Wales only) as well as the national census, taken every ten years from 1841. After 1840, we have these two uniform, nationwide reference sources through which to locate our ancestors and track their movements.

Before 1840 there are no comprehensive datasets covering the whole of the UK population: we are reliant instead on information gleaned from disparate sources that are not necessarily reliable or complete. So, pre-1840 research in Britain comes with a health warning: prepare to dig deep, it could be a long haul. But it’s also guaranteed to be utterly fascinating!

Finding Vital Records

Britain has a rich collection of what are generally referred to locally as ‘BMDs’ (meaning birth, marriage and death records), usually known in North America as ‘vital records.’

Vital records after 1837

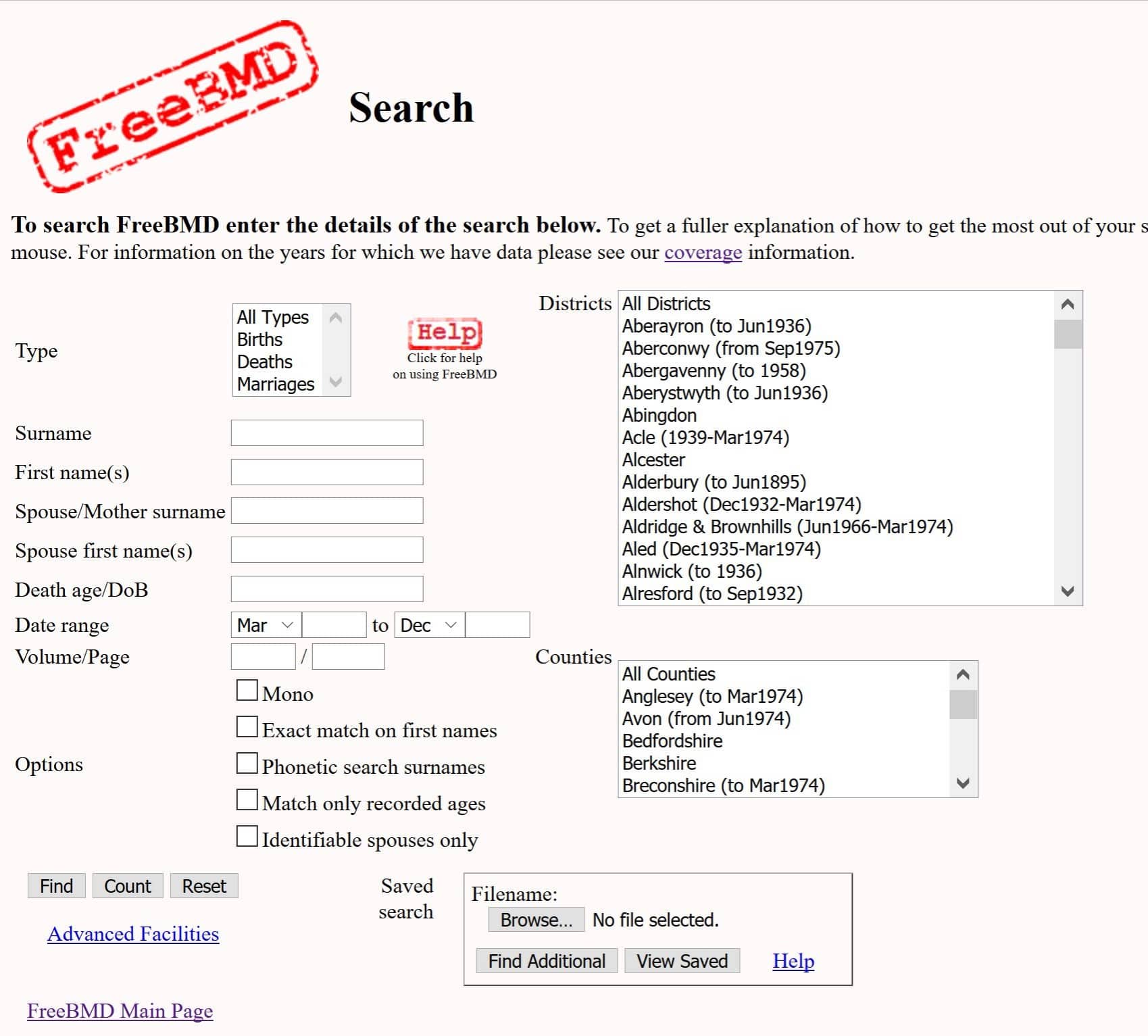

Civil registration of births, marriages and deaths started in England & Wales in July 1837. Under this system, all births, marriages and deaths had to be recorded by a registrar who issued a certificate, a copy of which was sent to the General Register Office (GRO) in London. The indexes to these registers (but not the registers themselves) are widely available online. The FreeBMD database has virtually complete coverage from 1837-1980, listing over 250 million English and Welsh birth, death and marriage records. Read Family History Daily’s in-depth guide on how to use the GRO index and FreeBMD for genealogy research here.

The GRO’s own online index covers registered births from 1837-1915 and deaths from 1837-1957. Although not as extensive as that available through FreeBMD, it has some distinct advantages. Birth entries list the mother’s maiden name and death entries give the age at death, neither of which may be available elsewhere (depending on the period being searched).

The GRO’s Index is free to search, though you’ll need to create an account. You’ll also need to use the GRO website to order certificates. A new, lower-cost service to deliver information from the registers as PDF files is also being trialed: these non-certified entries are not valid for legal purposes but are fine for family historians.

Civil registration was introduced in Scotland in 1855. The statutory registers can be searched free of charge at ScotlandsPeople (registration required), from where certificates may also be ordered. In Ireland, a similar system was introduced in 1864: the indexes together with digital images of the original entries are available at no cost on Irish Genealogy.ie. A separate service, GRONI, covers civil registration in Northern Ireland.

Finding UK Church Records

Parish registers

For hundreds of years, the main administrative body in Britain was the parish, at the center of which was the Anglican (i.e. Church of England) parish church. Baptisms, marriages, and burials were recorded in parish registers. These were introduced in the 1530s but often the earliest records have been lost.

Initially, these registers contained very limited information – a baptism may just have a father’s name, for instance. The introduction of printed registers ensured that events were recorded in greater detail and more consistently across the country, but this did not happen until 1754 for marriages and 1813 for baptisms and burials.

There were around 8,000 so-called ‘ancient’ parishes in England and Wales (i.e. pre-dating 1500) and several thousand more in Scotland. With the growth of towns and cities during the Industrial Revolution, some of these parishes were split to create new ones. Registers had to be collected from numerous different places and not all have survived.

Online coverage varies considerably: not all parish registers from a given area are necessarily available online and some may no longer exist. Hence, it is vital to verify whether a particular website covers the parish you are interested in and for the time period you are interested in, so as to avoid following false trails. FamilySearch has lists of parishes in England and Wales with dates of their surviving registers, as well as maps of parish boundaries.

Many of the pre-1840 parish registers (and some from later periods) have been transcribed. FamilySearch has a good collection covering all of England and Wales. FreeREG also has a database of over 40 million records transcribed by volunteers: coverage varies considerably, being reasonably comprehensive for some counties and patchy for others. Many local FHSs have also transcribed registers within their area which may be searched via their website or purchased as downloads or CDs (see the FFHS gateway above).

In some counties, new parish register transcriptions have been released as part of tie-ups between local archive services and commercial providers. These can be thought of as ‘official transcriptions’ and are important for two reasons: first, they offer full coverage of the area concerned (which other sources may not); and second, they generally include images of the original register pages (useful for checking the information given). New ‘official’ collections are being published all the time.

In Scotland, the church (or ‘kirk’) registers are referred to as Old Parochial Registers. These are now held by the National Records of Scotland and may be searched and consulted as digital images on ScotlandsPeople (pay-per-view). Again, FamilySearch has lists of parishes and their records.

Non-Conformist Records

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was a period of religious turmoil in Britain. Many refused to accept the new Protestant religion and sought to adhere to their Roman Catholic faith. Meanwhile, divisions emerged within Protestantism that led to the formation of new denominations that did not follow the creeds and interpretations of the Established Church (and hence became known as ‘Non-conformist’).

Thus, for any given area there may be separate records for Roman Catholic and Non-conformist places of worship alongside those of the Anglican parish.

Until recently very few Catholic records were available online. The Catholic Heritage Archive on FindMyPast has collections from the Archdioceses of Westminster and of Birmingham, covering areas around London and Central England respectively (subscription required, a free trial can be found here). A new database listing over a quarter of a million English Roman Catholics has been created by the Catholic Family History Society (CFHS) and will eventually be released online.

Ireland remained predominantly Roman Catholic. Church registers from the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland are available on Ancestry and may be searched free of charge in the Irish Records Collection at FindMyPast.

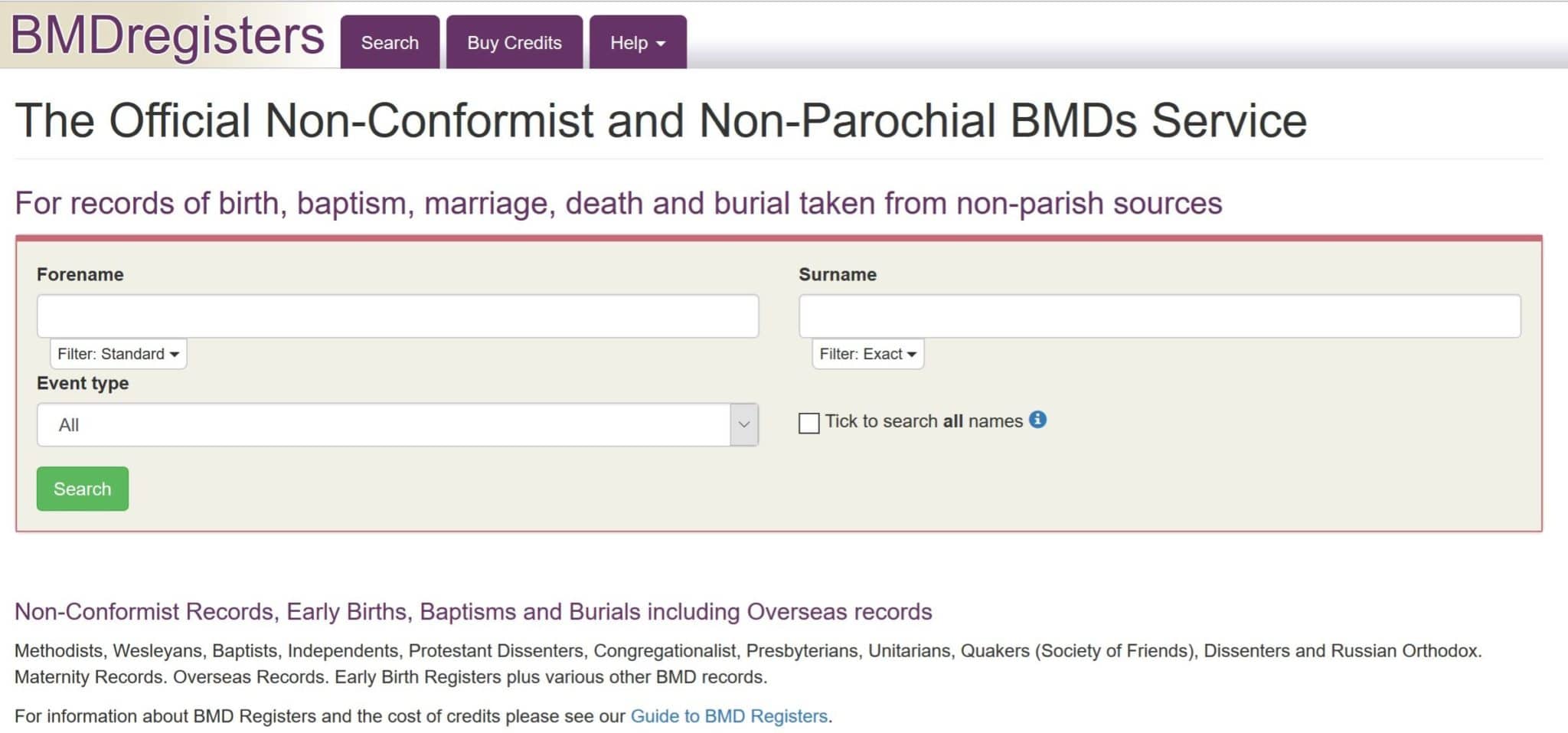

Non-conformism was especially strong in industrialized areas in central and northern England and in Wales. Records of nonconformist chapels held by the National Archives (a small proportion of the whole) can be searched at BMD Registers, a pay-per-view website. For others see FamilySearch, CROs, and local family history societies.

Finding UK Graves and Memorials

With many of the graveyards around churches full to bursting, during the nineteenth century, it became more common for people to be buried in municipal cemeteries instead. Deceased Online has cemetery registers from across the UK and is free to search. The National Burial Index lists church and municipal burials from transcriptions made by local FHSs and is available to purchase as a CD-ROM and partially available online through FindMyPast. The free to use FindAGrave database also provides some UK coverage.

Cracking the Census for Britain and Ireland

The census is the go-to resource for family historians seeking to track down their British ancestors from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. Although not the first to be taken (see below), the 1841 Census was the first to record the names of the whole population. Subsequent censuses have been taken at ten-year intervals and remain closed for 100 years. Thus, the most recent census available to us at present is that for 1911.

The range of information recorded in the census grew over time, to the benefit of modern-day researchers. From 1851 the data included: age, address, relation to head of family, marital status, occupation or trade, where born, and whether blind, deaf or dumb. This last question was modified slightly in subsequent years.

1901 saw the addition of questions on employment status and home-working, and in 1911 further details about marriage and children were asked that are of great use for family historians. This was also the first census to be completed by the householder themselves, rather than an enumerator, so we get to see our ancestor’s actual handwriting.

The 1841 Census has two important limitations. First, the ages of adults were rounded down to the nearest five years. So, for example, someone recorded as “age 40” may be anywhere between 40 and 44. Second, place of birth is indicated only as “Whether born in same county” (answer Yes or No), with a separate column for those born in “Scotland, Ireland or Foreign Parts” (marked as S, I and F respectively). Both of these factors can make it more difficult to identify people in earlier years, so it is best to verify with a later census if possible.

Accessing the British Censuses

All of the British censuses for the period 1841-1911 (covering England, Wales, Scotland, Channel Islands, and Isle of Man) are available to search free of charge at FamilySearch.

From a list of search results it is possible to click through to the detailed entry, which lists full information not only for that individual but also for the rest of the household. Images of the original census pages may be viewed either through FindMyPast or at an LDS family history centre.

FreeCEN aims to provide free Internet searches of the nineteenth century UK census returns and is a sister site of FreeBMD. At present, around 50% of the entries from 1841-1891 are available: check if the area you’re interested in is covered in the list of FreeCEN database coverage.

Ancestry, FindMyPast, TheGenealogist, and MyHeritage all have full coverage of the UK censuses available on a subscription basis. The search experience can vary between sites: you may like to take out a trial subscription to see which you prefer. Remember, these are huge datasets and errors are commonplace – if you can’t find the person you’re looking for at one site, try another – this way you can potentially detect any mistakes in the way the data has been transcribed.

Ireland (including Northern Ireland) is a bit of a special case here. All of the nineteenth-century censuses were lost in a fire and only those for 1901 and 1911 survive. The good news is that they are available to researchers free of charge through the National Archives of Ireland, as well as through commercial websites.

Censuses Before 1841

The first census was taken in Britain in 1801 – partly to help with planning during the wars against Napoleon – and the exercise was repeated in 1811, 1821 and 1831.

Unfortunately for family historians, very few of these early censuses have survived and, in any case, the information they contain is sketchy. Nevertheless, where they exist they can be a useful resource. Check the websites of local archives and family history societies for the counties you’re interested in to see if any survive and how they may be accessed.

In the absence of censuses that provide universal listings, for the period before 1841 we have to fall back on substitute sources that cover at least a significant proportion of the population.

Electoral registers, first introduced in 1832, show who was registered to vote in elections. In the period before the universal franchise (not introduced until 1928), inevitably this means they are biased towards men and property owners.

First mandated under an Act of 1696, poll books fulfilled a similar function prior to the introduction of the secret ballot, showing not just who was eligible to vote but also for whom they voted. Again, local archives and family history societies are the best means of finding out what is available.

At present, relatively few of these resources are available online. Ancestry has a good collection of poll books and electoral registers for London, and FindMyPast has some for other locations. Both sites have the modern-day electoral registers (2002-2014), which can be useful to track down lost cousins. This is not as useful as it used to be, however, as many people now choose to opt-out of the public register for privacy reasons.

Where There’s a Will

Wills and associated documents, such as inventories, are a key source for family historians. They can be a rich source of names that help to confirm family relationships, while the terms of the will – such as bequests of property and possessions – can give detailed insights into their lives.

For England and Wales, the key date as far as probate is concerned is 1858. Before this date wills and administrations (for those who died intestate) were dealt with by a complex network of courts administered by the Established Church. In 1858 these church courts were replaced by a single, national system administered by the State.

Finding a will after 1858 is a cinch: simply look for the name of the deceased in the National Probate Calendar which covers the period 1858-1996 and is free to search. Bear in mind that a will may not have been proved for a year or more after the death (and sometimes considerably longer). Once the relevant entry has been located in the calendar (index), a copy can be ordered online. It’s supplied as a PDF file within your online account, usually within ten days.

Finding a will before 1858 can be a very different story. The ecclesiastical (church) courts operated at several different levels and their jurisdictions did not necessarily coincide with county boundaries.

In some cases, a will was proved locally in archdeaconry or diocesan courts (a diocese is the seat of a bishop). In other cases, it may have been proved in either London or York (which were the seats of so-called ‘prerogative’ courts). Certain parishes, known as ‘peculiars’, had special status and maintained their own courts. As I said, it’s complicated!

The Prerogative Court of Canterbury (PCC), which sat in London, was the most important of these courts and dealt with relatively wealthy individuals living mainly in the south of England and most of Wales. PCC wills can be searched for free at The National Archives Discovery Catalogue, with downloads available at a modest charge. Records from the Prerogative Court of York, which fulfilled a similar function for northern England, are available on FindMyPast.

FindMyPast also has probate indexes for several other jurisdictions including the Dioceses of Coventry & Lichfield (which covered much of central England), Surrey and South London, and Wales. The London, England, Wills and Probate, 1507-1858 collection on Ancestry has records from various lower courts that covered London and the surrounding area.

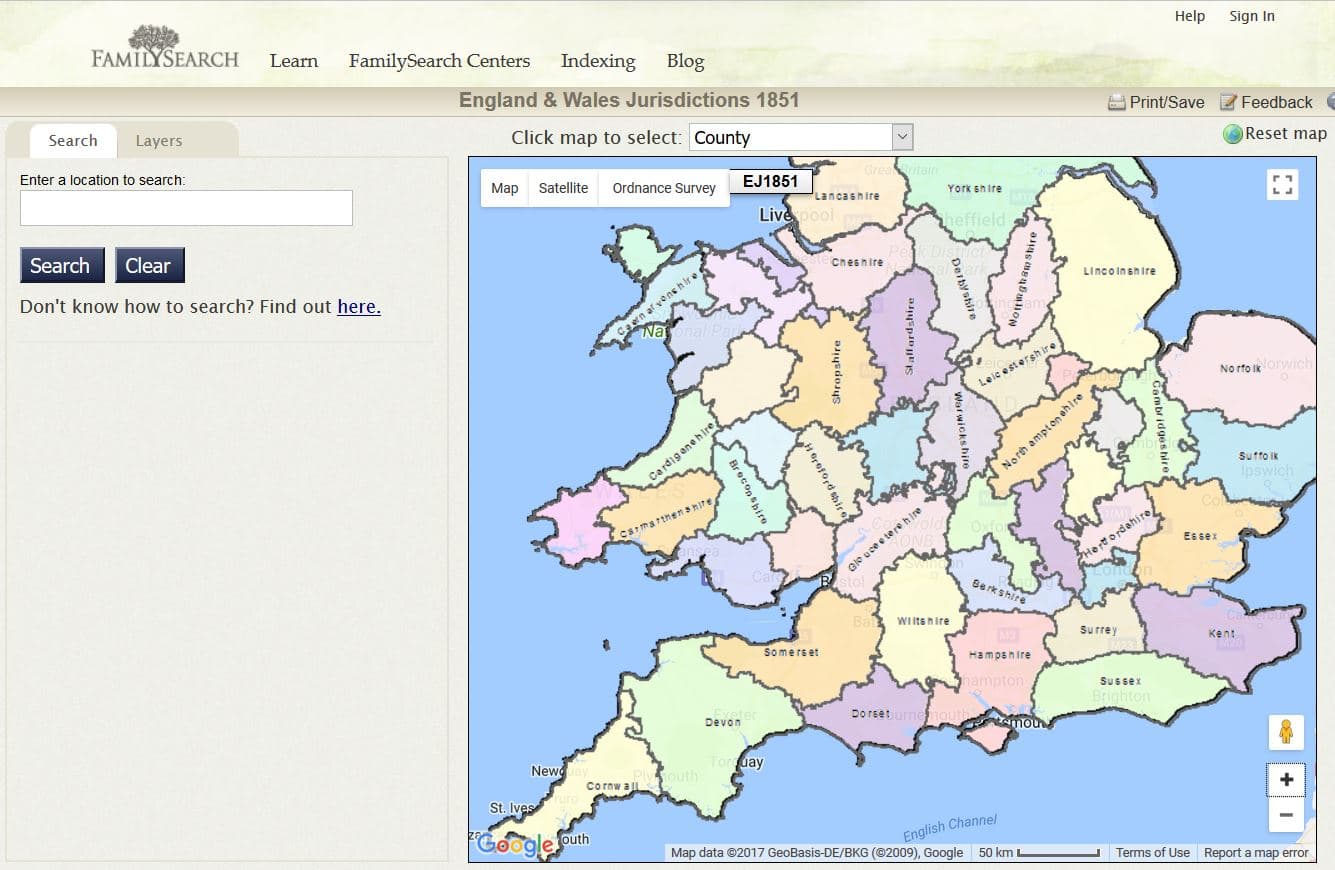

For other locations, see the websites of local archives and/or the FamilySearch Wiki to check holdings. The England & Wales Jurisdictions map at FamilySearch shows how Church of England dioceses related to historic parish and county boundaries. There are separate calendars of wills and administrations for Scotland and Northern Ireland, which are free to search.

In the coming weeks and months we will be publishing individual guides to England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland that will cover research in these areas in even more depth. You can find out when they are published by signing up for our newsletter below.

You might also like:

Free Genealogy Sites for Researching Ancestors in England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland

Have European Ancestry? Here are 30 Free Genealogy Sites to Search

By Mike Sharpe. Mike is a professional genealogist, writer, and lecturer and runs Writing the Past, a family history research and writing service. He works across the UK, specialising in research in Birmingham and the West Midlands region. He is a member of the Society of Genealogists, the Association of Professional Genealogists and several local and family history societies. He makes regular presentations on various aspects of genealogy and has written for family history magazines. His book Tracing Your Birmingham Ancestors is published by Pen & Sword.

Image: 1771 Zannoni Map of the British Isles, Jean Janvier, via Wikimedia Commons

Interesting feature and very useful for UK beginners as well as US. However you do not mention the 1939 National Register, which in effect acts as a census record – taken just before WW2 for identity purposes/ration books etc, ultimately our NHS service. Find it on Findmypast and Ancestry, and this website explains it: https://www.familyhistory.co.uk/1939-register/

Do a DNA test & that could link you to other family to give you a starting point.

No, I have zero information to work with.

My mum now in her eighties was adopted I have traced her family right back.

There are ways to do it

Have you any info at all to go on?

Looks interesting, but how does one search for birth parents without any details; for example, I was adopted in England when 3 months old.

Just one comment regarding Calendar of Wills – having lost money because it’s not generally put in articles – if in the Calendar is says “Administration” there is no will, and you will not get any more information than what is on the Calendar. Only if it says “Probate” is there a will to look at.