Thank you to Isabel Wu for creating this helpful guide to Chinese-American genealogy research.

The story of Chinese immigrants in America is one of hardship, struggle, perseverance, and solidarity. Although a good deal of Chinese immigration to the US has taken place more recently, it can be traced all the way back to the 1820s. This guide to researching your Chinese ancestry will help you gain an understanding of the history of this migration and discover techniques and free resources for exploring your own family’s past.

A Beginner’s Guide to Chinese-American Genealogy

This short guide is separated into three parts – history of Chinese immigration in the U.S., techniques to get you started with your research and, finally, genealogy sites and databases that offer (mostly) free records for finding your ancestors.

A Brief History of Chinese Migration to the U.S.

The earliest Chinese migration to the U.S. can be traced back to the revolutionary war period. Many Chinese migrants, and Hakkas from Guangdong Province under the Qing empire, came to Hawaii with Captain James Cook.

In the mid-19th century, a significant number of Chinese came to Hawaii to work on the sugar cane plantations. The state of Hawaii today holds a number of records on Chinese immigration, especially the passenger information of the early immigrants.

The first Chinese immigration wave to the mainland U.S. started in the 1820s – many were merchants or former sailors. Propelled by the mid-19th century California Gold Rush, and a desire to escape famine and warfare caused by the Taiping Rebellion, groups of Chinese laborers came to the U.S. for work in hopes of a better life.

Although some did make a fortune out of hardship, sadly, many of them were subjected to indentured slavery and became known as “coolie laborers.”

Many workers later became employed on the Pacific Railroad as well as in mining and laundry businesses. By 1882, one-third of the workforce in San Francisco was comprised of Chinese immigrants or their children.

The atmosphere of the Jim Crow era and the fear of employment competition stoked racial tensions between white Americans and Chinese immigrants. Congress subsequently passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 to ban Chinese immigration and to prohibit naturalization of Chinese immigrants.

To enforce the law, the government employed inspectors to investigate Chinese workers in the states, thus creating extensive records and files on Chinese immigration which are now available at the National Archives.

To further carry out the Exclusion Act, the U.S. government established the Angel Island Immigration Station in the San Francisco Bay, where around 100,000 Chinese people were detained between 1910 and 1940. Many Chinese people were deported back to China – some were even smuggled to Mexico and southward.

In 1943, in an effort to strengthen the allied relationship with China during World War II, the Congress passed the Magnuson Act, which allowed Chinese immigrants already residing in the country to become naturalized citizens.

The second wave of Chinese immigration came during the 1960s when President Lyndon Johnson finally revoked the Exclusion Act. The end of the immigration ban (coupled with the devastating effects of China’s Great Leap Forward policies in the 50s and the Cultural Revolution in the 60s) welcomed another surge of Chinese migration into the U.S.

The third wave of the Chinese migration came in the 1980s when the relationship between the U.S. and People’s Republic of China resumed at the end of the Cultural Revolution. More Chinese also came following the tragedy of Tiananmen Square, fleeing the feared subsequent repression.

As of 2010, there were 4,948,000 people of Chinese descent living in the U.S. (according to census), making up approximately 1.5% of the total population.

Keep this history in mind – as your ancestor’s date of entry to the U.S. may determine which documents and files are best to look into first.

Search Strategies for Finding Your Chinese Ancestors

Now, let’s get into the nitty-gritty of genealogy research for your Chinese ancestors.

Like any genealogical research, you should start your investigation by collecting information from family. Ask parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins about the names, dates of birth and deaths of relatives to trace your family lines. Family albums and written records of family members will also be very helpful.

Write down the first names, surnames, and the approximate years of your ancestor’s stay in the U.S. Ask relatives about prominent members of the family clan. Note the names (surname, maiden name) of parents, spouses, siblings, children, and other relatives including divorced members. Store everything in your family tree program.

Vital records such as identification cards and birth/death certificates are a good place to start. Divorce papers, property records, and immigration records are also a great source of information.

Once you are done gathering information from family, you can start searching for records online that might help you identify a country of origin and other important details. If your ancestor came to the U.S. or Hawaii before 1882 (and never left and reentered the U.S.) it may be hard to find any files from immigration data. You may, however, be able to find information about your ancestor from ship records, such as passenger manifests. Hawaii offers a research page here, which includes those who stayed in Hawaii and others who simply passed through on their way to the mainland.

If your ancestor came to the US after 1882 or reentered the country after that time, you may be able to find his/her information from various immigration records.

Mostly Free Online Databases for Researching Your Chinese Ancestry

Berkeley library is a good place to start. This database contains Investigation Arrival Case Files from San Francisco and Hawaii. This searchable database is a good place to start if your ancestor arrived during the Exclusion Era as it contains INS files between 1884 and 1944.

Census records host a wealth of information for genealogy research. The most recent census you can search right now is from 1940. Want to know more? Read The Ultimate Quick Reference Guide to the U.S. Census for Genealogy.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services branch of the Dept of Homeland Security (USCIS) offers services for searching for genealogical records. For a fee, you can request a copy of a record from the Naturalization Certificate Files (C-files) from 1906 to 1956, Alien Registration Forms from 1940 to 1944, Visa files 1924 to 1944, Registry Files from 1929 to 1944, and Alien Files dated prior to May 1, 1951. Look here for more information.

Hawaii State Archives Digital Collections allows you to search most of the Passenger Manifests for ships coming to or from Hawaii between 1843-1900. This database is particularly useful for those ancestors who arrived in the U.S. before 1882.

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) holds Individual census records from 1790 to 1940s. This page lists all the immigration information and historical context pertaining to Chinese immigration in the U.S. This is a great place to search for your ancestors that lived in the U.S. during the Exclusion Era.

Ancestry.com

You can search the following records free through Ancestry.com but accessing them will require a paid membership. A 14 day free trial can be found here. Please note that we are an affiliate partner of Ancestry.com and may earn a fee if you decide to subscribe to their services after clicking on a link on this page.

- U.S., Naturalization Records, 1840-1957

- U.S., Chinese Immigration Case Files, 1883-1924

- New York, Index to Chinese Exclusion Case Files, 1898-1943

- Hawaii, Index to Chinese Exclusion Case Files, 1903-1944

- San Francisco, California, Chinese Passenger Arrivals and Disposition, 1903-1947

- Portland, Oregon, Chinese Immigrant Landing Records and Applications for Admission, 1882-1903

- California, Chinese Arrival Case Files Index, 1884-1940

The National Archives website also provides additional free information on researching your Chinese ancestors including an in-depth guide and helpful resources here.

Shanghai library may be the world’s largest database for searching Chinese lineage. The library holds nearly 50,000 family trees.

Family Search, operated by the Genealogical Society of Utah, holds the world’s largest collection of genealogical records in the world. The page on Chinese genealogy provides helpful resources such as how to read a Chinese genealogy book. Here you will find links to various topics such as background information, different record types, and how to interpret certain records. Their China Collection of Genealogies and associated guide provide a place to start for researching ancestors in China.

House of Chinn is an extraordinarily useful site to get educated about Chinese genealogy. It provides a detailed explanation including background information, use of special terms, and historical information about names. It also provides beginner’s guides to researching family history in China. Once you are done with your search within the U.S., this excellent guide will take you to the next step – finding information in mainland China.

Siyi Chinese Genealogy is an educational website for the genealogy of families from an area of Guangdong, China. This website has a list of genealogy sites featuring family trees of prominent Cantonese surnames as well as details of the site owner’s journey of finding her/his ancestors, which may offer some insight for your own search.

My China Roots is a paid service for tracing Chinese lineage. If you have enough in your budget and are tired of mining through piles of information, you can use their services to find out more about your family history.

Besides tracing ancestry all the way to the villages of your forbearers in China, it will also connect you to the village and organize a trip for you to visit your ancestor’s home.

Sheau-yueh J. Chao’s book In Search of Your Asian Roots: Genealogical Research on Chinese Surnames, includes a concise genealogical analysis of more than 600 names and their variants. The book also introduces various useful methods to trace Chinese lineage and in-depth information on Chinese genealogy research. Check out her very informative video presentation on how to conduct genealogical research on Chinese ancestry and how she found her ancestors. The above link points to the paid Google ebook, but you may be able to find a local repository that offers the title for free.

Good luck with your search!

Isabel Wu is a former magazine writer and editor with a Masters in history. She wrote her thesis on Chinese immigrants’ sojourns in Mexico during the Mexican Revolution period. She enjoys writing about the bygone times and helping people reconnect with their past through research. English is her working language, but she also conducts research in Chinese, Spanish, and Korean.

Special thanks to my good friend Lauren Souther, Archives Technician at NARA, for pointing me to the useful sources the National Archives have on Chinese immigration and Chinese in the U.S.

You Might Also Like:

50 Free Genealogy Sites to Search Today

Free Genealogy Research Sites for Every U.S. State

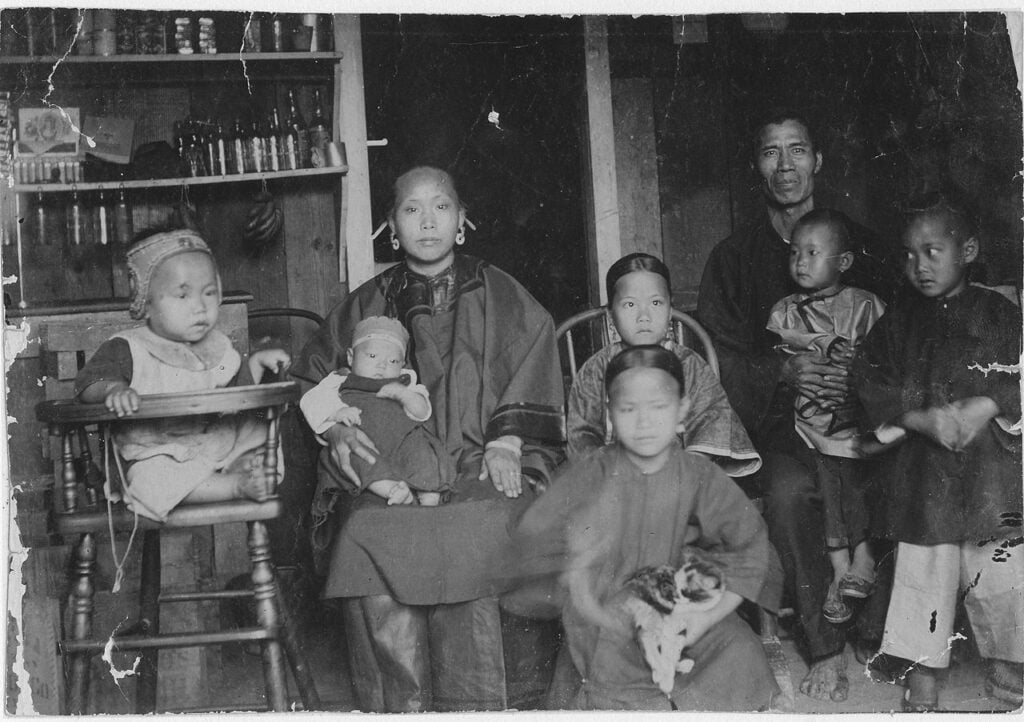

Image Credits:

- A Chinese Family in Honolulu, Hawaii, 1893. Courtesy of Hawaii State Archives

- Immigration Interview on Angel Island, 1923. Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration

- Lee Family, Butte County, California, 1920. Courtesy of California State University, Chico via California Digital Library