Family history research is a fascinating and rewarding hobby, and it’s getting more exciting all of the time. With new records and tools and research methods appearing every day, there are seemingly endless opportunities to explore and collaborate.

But, as most of us already recognize, there are also endless opportunities to make mistakes. And, in the connected world of online research, those mistakes can spread like wildfire.

Genealogy is collaborative by nature and sharing information is a big part of the journey for many of us. After all, who wants to do research in a bubble? Genealogy is about connections and none of us would be able to expand our research to any great degree if it wasn’t for the spirit of sharing.

But, as we discussed in an earlier article, sharing has to be approached cautiously (whether we’re borrowing from someone else’s tree or offering our own up to others). Because it is so easy for someone to simply grab our information and run with it, we must be extra cautious about the data we place online.

And this brings us to one very important part of our family history research that can easily go awry — the connection between generations. It’s becoming common, much too common.

More than any other area, this one is the most vulnerable to the kind of mistakes that can completely crush the accuracy of an entire branch of our tree. Any person who has been doing family history research for any length of time has seen this in action, an incorrect parent or parents on a family tree, sometimes copied again and again by others.

Of course, a ‘bad connection’ can happen to anyone quite easily and is not always a matter of poor research methods. Most of us have made a mistake about parentage at some point or other. But usually, if we’re invested in our research, and if we’re concerned about proper sourcing, we will catch the error fairly quickly.

So why is this mistake so widespread in public family trees? Because it’s an easy error for any family historian to make, no matter how careful they are. And, let’s be honest, not everyone is interested in developing a highly accurate tree. Some family historians are only in it for the short-term, just slightly curious about their family’s past. And there’s nothing wrong with that. Genealogy research is supposed to be fun and can be a simple, passive hobby for someone and still enrich their lives and the lives of others.

But it is for this reason that each of us must take responsibility for what we choose to believe about other people’s trees, in addition to what we add to our own.

Before we borrow or share information we need to ask:

Am I sure that the connections I am seeing in this other person’s tree are accurate? Are there quality sources to back the connections up? Does it appear that this researcher was careful about the information they added?

Am I sure that I’ve made correct connections in my own tree? Am I ready to share that with others in a format that encourages copying?

If we answer “no” to any of these questions, it is time to step back and consider our course of action.

If you’re thinking at this point that you don’t need to worry because:

a) you never copy other people’s trees or

b) you know you did due diligence on every single connection you made in your own tree,

that’s great! But you might also want to consider that this type of mistake is so common that it was only recently discovered that an entire line in Hillary Rodham Clinton’s tree was completely wrong. Was this because of random copying and sloppy research? Maybe, but more likely than not it happened in spite of careful research.

The researchers in this case had made one of the most common ‘bad connections’ — incorrectly using the identity of a similar individual with the same name in a tree. It is not at all uncommon to find that there is another person with the same name as your ancestor born in a similar location on a similar date. This is especially true when you are dealing with a common first name or surname, but can happen even to those with seemingly uncommon names.

And, of course, if you accidentally use the information for the wrong individual in your research you will get off track with an entire line very quickly.

But we can avoid this.

The most important way to stop ourselves from accidentally traveling down the wrong path in our research is to make sure that each and every connection we make is as accurate as we can possibly determine. It is important not to make assumptions in our own research and not to simply take another person’s research at face value.

When adding a new generation to your tree make sure you:

Do not simply copy another person’s research. Carefully examine every single source that person has, and if proper documentation does not exist, find it yourself.

Have an acceptable combination of ‘connecting documents’ that tie your generations together. While these sources will change from situation to situation, they should always include documents that clearly show a grown child you are researching and the parents together. This may be a marriage document or death record to start with. Find this information first and then work backwards in time to further verify the information with birth, baptismal, census records and others. Make sure the picture you are forming makes sense and don’t overlook discrepancies or usual dates — they could be a sign that you have gone off track or something is amiss. Look for consistent data and make sure that variations in sibling’s names or ages, people’s birth dates, or family name spellings are just variations and not a sign that you have the wrong individual.

Avoid adding documents to your tree that you can’t be sure actually relate to your ancestor just because the name and birth year are similar. Sometimes we do have to take leaps of faith in genealogy research, but we need to take as much time as possible to make sure that the document is really an accurate addition, every single time.

Don’t take big leaps. Once you have found the parents of an ancestor, work backwards carefully through the records, making connections wherever you can, to make sure you don’t accidentally assign incorrect individuals to your tree.

Be cautious about step parents or adoptive parents. People remarried and when they did they often adopted children, legally or not. If a person remarried when his/her children were still at home the new father or mother may even be listed on a marriage certificate or death record as the biological parent. Sometimes there are virtually no clues to make this apparent so always make sure you find a birth record for your ancestor once you have secured proper connecting documents. Most family tree programs have an option to add step or adoptive parents so that you can record the importance of this person in a child’s life while still maintaining an accurate biological line.

When in doubt, always double check. Don’t leave important connections to chance. Noone wants to spend years researching a line only to find it’s not even their own.

If you have any doubt at all about any of the connections in your tree, we encourage you to take the time to examine each one and make sure you have the sources needed to know that you have the correct information.

And if you do not — and cannot find documentation to prove the connection — consider removing the information from public trees or making clear notes about your doubts. A simple question mark after a name will alert a fellow researcher to your concern. You can then follow that with a note that is attached to the person in question.

And if you see another person’s tree that shows an incorrect line, take a moment to drop them a note so that we can all help to avoid one of the most common and destructive mistakes in genealogy research.

By: Melanie Mayo | Editor, Family History Daily

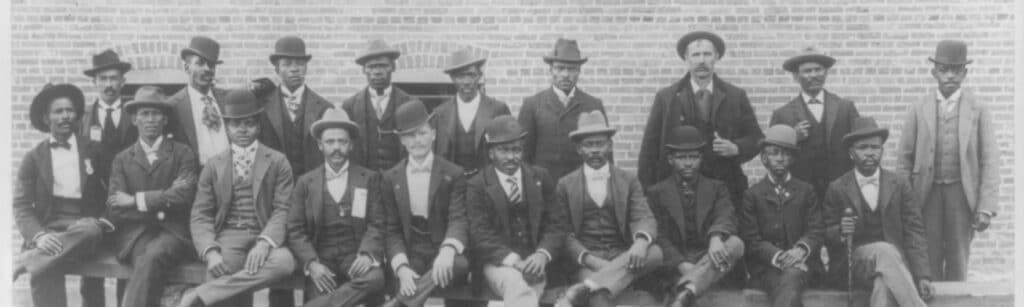

Image: Portrait group of African American Bricklayers union, Jacksonville, Florida. Abt 1899. Library of Congress

Originally published Feb 2016

Census records cannot always be counted on. My great grand mother is an example. When I first found her in the census it appeared she was many years younger than her husband. Going back 10 years, there was not as much differences in their ages. An other 10 years back and she was about the sameage as her husband. It appears she was only aging about 7 years every 10 year census. Quess who was home giving the census taker information every 10 years.

One big problem that the article didn’t bring out was that websites like Ancestry and FamilySearch have computers that “crawl” through the files and link people with trees. These are not always accurate. I’ve had to delete links to people who were not in my tree at all.

Regarding adoptions: my husband’s birth record has been expunged and the birth certificate only shows his adoptive father – my husband was adopted at age 13! If I did not personally know his biological father’s details, I would have no way of finding out or documents to prove this.

you are not wrong! Plus, for family members who work on genealogy in FS, you cant see each others’ work, so there could be half a dozen of you, with wrong information and different ID numbers. It drives me mad!

Check your sources most of the time you can match sources to people in the tree. It is helpful if finding a roadblock, to see if you can find a locality historian. I had a road block and I found one and they helped me to match my gggrandmother to another marriage. Which i would not have found and concusi records of her moving and having other children.

This is a brilliant and timeless article.

My maternal grandmother’s line was completely mangled by some zealotry when in a different branch of the tree, the collation of information to be published into a book for a family reunion – which none of us ever knew about – had, from my great grandmother down, the generations mixed. My siblings and I were recorded as siblings of my mother; my mother’s siblings were attributed to an aunt. It was just a mess and quite disappointing. And, if taken by gospel by various branches, where we are talking about 5th cousins, then their research compounds the error.

Sloppy.

Great advice, that I always follow, but I have a question:

How on earth can you prove that relationships are biological once you get past the early 1900’s? (at least in most rural places…) I am very careful to not proceed further down a line without proof, but there just isn’t any proof in most of my lines in the early, rural South, so I have been stuck for a long time. (I once saw a list of “burned counties'” in one of my southern states, and all of my counties had had fires in the court houses at least one since my ancestors had lived there – sometimes more than once!)

I have run into such a problem with my tree that I’m not sure entirely WHAT to do.

Let me just state first, this is regarding my dad’s side of the family, and I at this point know more than he does, so asking him will do nothing. My grandparents have both passed many years ago, so there’s literally nobody I could talk to about this.

My great-great-grandfather’s name was Thomas F. Reynolds, and I’ve traced our connection accurately, but I’ve hid a roadblock, ALL because of his birthday. Now, the obituary for him along with his actual tombstone show his birth year as 1863. The 1910 census ALSO shows him being born abt 1864. However, in the 1900 census, someone reports his birth year as 1859. In searching for him via younger year census records such as 1870/1880 I find a Thomas Reynolds, living in the area he was born in, sharing the same father’s name, but his age puts him as being born or around 1859. So I have a crux. Do I really believe census records, one of which contradict the rest and match more factual information such as obituary, tombstone, AND the Illinois Deaths and Stillbirths Index, all saying 1863, or census records from 1860/70/80 showing the same family, same area, same members, but showing HIM being alive and existing in 1860, three years before he was supposed to be born? Another crux is, his father’s name was John Reynolds, and as you can imagine, especially with Irish families (John immigrated from Ireland), the name is common, so this could be another family. Problem is, I can’t seem to find another Thomas Reynolds in that area. I would love to keep tracing and to find out more, but it’s extremely difficult in this case. I don’t want to be wrong, and taking a leap like this could carry me off course quite a bit.

Any advice?

Jim Jones, et. al.

KUDOS, Jim Jones! Your remarks are spot-on! I, too, have come across cousins who refuse to fix errors, but that’s on them. My work isn’t perfect, but I’m still working on it to make as near perfect as possible. That’s the best I, or anyone can do. As you suggested, we’re all in this together. Geneticists tell us that everybody alive on Earth today is a descendant of one man who lived between 160,000 and 200,000 years ago. (Carbon data is less and less precise the more ancient the object being dated is.) So we’re all cousins, like it or not — we’re all a true, genetically related Family of Man — in addition to our interrelatedness as members of “The Family of Man” in the context of the Spiritual Community.

Genealogy is inherently a shared activity. It can’t be fully accomplished by any other means,, in spite of the musty old court houses, libraries and all the digitized materials online. It still requires human interaction to ‘seal-the-deal,’ to exchange pertinent data from one family unit to another, related family unit in order to ultimately complete a family pedigree and history, even if it requires a middle man, such as an institution, to accomplish. What does this mean? What’s the bottom line here?

The bottom line is simple. Family genealogists either work responsibly, or they don’t. Some of the difficult issues noted in Jim Jones’ comment facing researchers are the result of the erroneous work posted online. That’s what happens when people don’t work responsibly. Here are some possible reasons why some individuals don’t work responsibly: 1) They don’t know any better, 2) They’re too lazy to do the work, or 3) They simply throw a pedigree / history together “slam-bam” (in a hurry), without any thought, review, or analysis and call it day. Or it could be a combination of any of those characteristics noted above.

Whatever the case, if one chooses to don the mantle of “Family Historian,” or “Family Genealogist,” one is behooved to also accept the responsibilities that come with said title(s), i.e., Honesty; Integrity Beyond Honesty; Earnest, Sustained Effort; Responsibility; Accuracy; Documentation and Clear Reporting.

Seek the TRUTH above all else. Be grateful when someone points out an error and Thank them for it. They just did you a favor. Use that opportunity to swap data. They may have a jewel of information just waiting for you to add to your data treasures and share your treasure with them. Pay past kindnesses that you couldn’t return forward to those who can’t help you. Build good Karma for yourself. It will bring good things back to you.

Kindness begets Kindness. Anger begets Anger. If you share and get nothing in return, don’t get angry. Feel sorry for that person. They have to live with their Karma and you have to live with yours. That’s happened to me several times when they said they’d share, but didn’t. So What!! No babies died! Right? Nothing bad happened to me because they didn’t share, but they didn’t keep their word, so that’s on their Karma.. That’s a responsibility they failed to keep..

Keep your word. Always do the right thing, not what’s easy, or convenient.. Be responsible. Treat our cousins with respect and try to love them, because they’re just like you, really. If they misbehave, it’s because they’re temporarily messed up. Let it roll off and go on about your business.. FORGIVE! That’s much healthier for YOU!

Everything you need will come to you eventually, if you remain calm and relaxed. Focus your mind on what you need for a moment, then let it go. Relax, remain calm and just go about your research in a casual way. You’ll be literally shocked by how much more productive you’ll be and how much data you’ll find. It will almost seem Miraculous. Trust me, it works. TRY IT YOURSELF! I double dog dare ya.. Tell me how it goes.

Blessing to All.

Your Genealogy Cousin

David

Discretion is key when looking at the hints. I followed a hint for an ancestor, supposedly living in Illinois. Had a baby born and it died, in Illinois. This baby, in 1894, was taken to Vermont for burial in December? I don’t believe that for a New York minute! Making it better: both parents were also laid to rest in Vermont.

If you are not from a place where you have lots of snow, you may not understand why I disbelieve traveling from Illinois to Vermont in December. You can Google winter pictures in both states.

I’ve never really known a whole lot about where my lineage goes, only knowing how far back to my great grandfather. When doing research on this, you are right that you shouldn’t copy someone else’s work. You wouldn’t want to put some info up and then not have it be right.

I wanted to sign up for my free two weeks using my Pay Pal account for funding when it went to Pay pal site it only wanted the bank associated with this account or my credit card used in connection to my account it would not just accept Pay Pal as a source whats up with that ?

Landlyststien 19. 1. th. 2635 Ishoej.by Denmark

I am with Ancestry and paid for the World records but am unable to find Catholic records for my family in England. Also, they do not show a copy of signed birth, marriage or death records. They only show registrations which are of no help, I know the people I am looking for were born, married and died. The marriage again is only a registration and shows just one person so I never know if it’s the right person. They never show birth records only that the person was born, so I can’t see the parents. Are there any other sites which I can go to to find this info. The Irish records are so much better, they show everything.

Amen Jim, I could not have said it any better. i had not thought about putting notes on other people’s trees, but may start doing so. I do put question marks and notes on people in my tree, that I am unsure of. If I don’t add the person, I don’t get hints on them. At times, I add a person but don’t link them to a family until I have found documentation, so there are ways to work around just adding incorrect people.

I have sent messages to other people, using Ancestry’s “contact” but generally they don’t acknowledge my messages. I will contine with my “public” tree, knowing no one can change my information but me!!

Thank you for mentioning birth certificates and the adoptee to whom they belong. Only 7-9 states in the US have totally unrestricted access for adoptees wanting their OBC (original birth certificate. ). For the others either they have only the revised/adoptee’s birth certificate which lists the adopting couple as the birth parents, no place of birth (i.e. hospital) and no other information normally found on a birth certificate. If the adoptee is not born in the state of adoption, there will be only the revised certificate. Accessing the original document can be a nightmare.

I strongly advise adoptees NOT to mix apples and potatoes.. don’t put adoptive parent and their children etc. in the tree-period! Make a separate one for them if you feel need to do so, but don’t mix them, and don’t put a child that you may well call sister but who is in fact another adoptee in the same group as you. It is bad enough that we are called upon to explain ..but far worse when we are not…. For instance, I have both the court prepared birth certificate created by the court and dated the day of the Adoption decree as well as my original birth certificate. but if I did not also have the final adoption decree no one could ‘marry’ the two birth certificates because the information om either is much different than one another. after my death, even though the documentation is there, those unfamiliar with the legalese won’t be able to comprehend how the two birth certificates and the final adoption decree are related.

Adoptees are the last group to continuously be denied equality under the law. And often documentation is simply not available because of sealed records and closed adoption procedures. Some states allow petitions to the courts to access the documents…. but a petition is no guarantee that the court will grant the request.

With the advent of DNA analysis, adoptees may be able to locate family, but may open too many cans of worms in the process. And the truth is that siblings often don’t know they have siblings or even that they are adopted.

Caveat: there is not documentation available for every circumstance, particularly in cases of adoptees. And some that was available at some time in the past has been purged-gone forever.

Regarding the closing comment in your article- “And if you see another person’s tree that shows an incorrect line, take a moment to drop them a note so that we can all help to avoid one of the most common and destructive mistakes in genealogy research.”- what should you do when that information has obviously already been copied over to other people’s trees? If you can’t determine the origin of the “mistake,” should you contact each user in whose tree that mistake appears?

My half-uncle died in February 2000 in Mississippi, yet I have found numerous trees in which the date and place of death of a person with the exact same name who died in Washington state was entered for my half-uncle. I had personal knowledge of the circumstances of his death since I attended his funeral but I have not actually seen his death certificate. I have contacted a few of those perpetuating this incorrect information. Should I provide a copy of his death certificate which I possibly could obtain from his only surviving child?

Thank you! I appreciate you confirming what I think about “other” peoples trees, both the good and the bad. I have pondered what to do about mistakes that one family member makes and everyone else shares! I will begin to leave comments which I was uncomfortable doing before. I will also add “?” to the heading of my ancestors when I’m not sure. To this point I have just kept them private. I am considering changing that designation to public, thanks to you.

There is one family in particular that everyone else has “my” 2 x great-grandfather dying in 1849…I have him with my great grandfather on the 1850 census…it changes EVERYthing! I will go back and leave a comment!

Thanks again for you comments and great suggestions.

We adopted our son in a “private, closed” adoption in the state of Missouri. We were put in touch with his birth mother by family members. His birth mother was very young and did not wish to abort as her family and the birth father’s family were encouraging. I snatched every bit of my son’s history that I could because I was afraid that I would lose it as they moved forward with their lives, and because I had done my research on “open vs. closed” adoption early on. Seeing how many adoptees went looking for their heritage, I wanted my son to have his already at hand. Most adoptive parents fear greatly that “their” child will dump them in favor of his/her birth parents. From that research I found that children simply want the truth.

What ultimately happened in spite of courts and their obliterated records, is that I kept in touch with my son’s birth mother and father, I share information and photographs with them, our child gets to see them whenever he wishes and all parties can participate. They love him, We love him. All those grandparents that could have had him in their lives now wish they had accepted us. What a special life they have missed. Those precious (to me) birth parents do not get in my face, I do not get in theirs, our children know of each other and have met (hopefully opening the door to adulthood ties), we share a lot with each other through social media. The court records are truths only to those who create those records. While we should seek and add to reference them as genealogists, we should also realize that they are not always the whole truth.

My son is now at age 17, beginning to show interest in doing his own family history, and has asked my help. I have been compiling what I know so that he can confirm from his birth parents and ask them what he needs to know.

Since his birth, I discovered that my great grandmother helped fund an orphan’s asylum in Missouri, yet lived in another state. She adopted as many children as she could and I don’t know yet how many are my blood kin, but because of my son, I know she loved them as if they were from her very own body. I will document as I find out, but in the end, I know that it is our relationships while we live that matter most.

most of my families were easy once i got them past the 1600s were they lived back and forth between england and america. the acadians were actually the easiest, they seem to be extremely well documented in canada, but most of the true french lineage is uncertain, although dna is beginning to help. i have a one name account with family search still…i use it for research only and have asked that no one add to the chart. it is not that i am unwilling to share, it is that i refuse the abuse by idiots.

geneology should not be INVOLUNTARILY cooperative. i have quit geni, wiki, and family search due to idiots that feel compelled with no experience and made up data, changing decades of research over what they ‘feel’ must be true. you have to beg, practically offer up a birth certificate and death certificate just to fix it. because as your ancestors disappear at the hand of some genealogy nazi, the citations you had entered go with them. i have over 90k people in my offline chart, there is no way i could police them against the know-nothing trolls online. if you have just a dozen people…fine. more than that, stay away from these nonsense sharing sites. DO NOT LINK YOUR OFFLINE LEGACY OR ROOTS MAGIC TO FAMILY SEARCH IN PARTICULAR. they encode all your family with their own numbers, and offer them up to unrelated ‘relatives,’ to be screwed around with, and automatically update your offline roots-magic of legacy files so even they are corrupted.

Unfortunately I have found a few in other trees on my grandfather listing him with the wrong parents. And it’s because, as you mentioned, there were a few George Washington Funderburg ‘s. I have sent messages to them that “this is why you can show no records for him” but people refuse to believe it. On another note, I have never merged from anyone else tree from the very beginning of starting my genealogy. I’m a stickler for documenting everything I see. If I see it it someone’s tree I research it myself……

I agree with everything you have stated here. Why people think it is fine to pull from my tree but keep theirs locked and will not share it terrible. I work very hard researching everything and if I’m not completely convinced something is correct or not I note it; a simple ? mark let’s everyone know I may have ‘issue’ with the information. I always message anyone that I find who has something incorrect to help them out. I offer my tree to them to look at my information and sources. Just wish everyone could be kind and helpful but, it seems to be to much to ask. Sad really.

I completely understand your angst. I had a woman who attached records and precious pictures, and worst of all – my own memories of many of my ancestors. When I pointed out to her that she was not on the right trail, she ignored me. When I posted comments on her tree, she had the gall to have ANCESTRY write me and let me know that they would cancel me because I was harassing this stupid woman. Sigh…so right now I have made my tree private, but then again, I think “why?” The damage is already done and the years and years of research and contacting obscure cousins was added to her tree with the click of a mouse.

Do you ever suspect people who show tens of thousands of “ancestors/relatives” on their tree? I sure do.

I so agree with Barbara.Official documents are only as good as the information received from the informants. I have found so many errors on death certificates . Also my great grandmother has an incorrect date on her headstone which was confusing until documents like her death certificate and will proved the correct date.Unfortunately her headstone is still incorrect.Census records can also be misleading and need confirmation from other sources. My husband was adopted and given a name of his birth father, we traced that line only to find when his DNA results came back , not one of the names we expected to see turned up but a name totally unknown is his exact match.

where to from here? who knows.

Thank you for taking the time to tell me why I should make my tree public.

Jim,

I applaud you and your response to the article. I hope more read it, and take to heart what you are saying. I’m a beginner at researching my family, but find many of the same things frustrate me. If only we would all be willing to share, the things that are just beyond our reach could come into focus.

Interesting read, but even more interesting comments. I have a very well-documented tree that many take from. Of course it has errors. They are minimal but they are there.

I despise private trees on ancestry because their owners can, and generally do, copy but do not have to share, and so I cannot see how they have used my research nor see what else they may know about someone in my tree that I may not know. Asking people to share a tree is rarely successful. There are many cases where I can see by the title of a document or photo that it is something I would love to have and will never be able to find on my own.

After I pass away, who builds on or leverages what I have done if my tree is locked away? No one. Most of my heritage is shared by others. Not all, of course, but most.

If we let foolish people who make mistakes, or just take ancestry hints at face value, prevent us from sharing what we know — especially when we are the only ones who know it — then we hurt each other. We share less. We miss opportunities to help others who are not as smart as we are (ha) or not as skilled.

I document when something in my tree is provisional so that anyone who looks can see it. I make comments on entries in other people’s trees that i know to be wrong or suspect may be wrong, and why i think so, so that other researchers who look at those trees can see my comments and decide for themselves what to accept. I thoroughly comment the media or photos I post instead of just a title or name. Takes time but also makes it easier for someone else to know whether my work is actually associated with a person in their tree.

The net gain from collaboration is always greater than the alternative, unless one simply cannot bear to part with “their” materials. When I am gone, I want my work to live on after me, and for materials that have come down to me to be part of our collective online history. Because my heirs could simply take it to the dump or lose it, and it never sees the light of day again. Gone from history permanently.

What is the point? I want what I know and have discovered to remain available. Because careless and “stupid” people will always exist the only way to fight that is to make the right info available so it can be found and considered.

Right now someone has put his great-grandfather into my Oscar Johnson family of Fredonia, NY and has copied all my pictures. His tree is wrong and I’ve told him his Oscar Johnson is NOT the same as mine. Will he fix it? Who knows? But anyone who looks at his tree will see my comments to that effect and will see zero records to document that new person in the tree. Also, I take the time to submit alternate data when a record like a death certificate has incorrect data.

That’s how collaboration works. Eventually and in most cases the correct or best information with the best documentation and sourcing prevails.

I can also tell you that I’ve gotten past many a blockage by noticing a tree among the ones ancestry suggests that has data that is unique and not just copied, even if practically unsourced, that provides enough clues to solve the problem. Because in this case they know something no one else knows. It is surprisingly common.

Same for findagrave. Yes, it can be wrong, and headstones often are, but submit corrections and add relatives. Most findagrave folks welcome them. They may want to see proof (good for them) but they are willing to make fixes.

In states like New York, which doesn’t allow a lot of its records to be added to ancestry, finding a NY state birth, marriage, or death record is well-nigh impossible. In many cases finding a relative on findagrave was literally the only starting point I had. In many cases the dates and ages from the stones are all we will ever have. If a county where a lot of your relatives lived is a burned county (like both Russell County, VA and Sullivan County, TN are for me), findagrave is often all there is.

Try your best to document errors and submit alternate data, and request fixes on findagrave. It only needs to be fixed once, but leaving it broken when you know better means it will remain broken for the future.

Thank you for this article, we can not emphasise enough the importance of genealogic data quality. And I don’t completely agree that many people don’t won’t to have a highly correct tree. I find that the professional genealogists don’t succeed in clearly explaning what factors make it certain that it’s correct. With all do respect, but when I summarise the article, it reads: find as much documents as you can, and be critical about it. Of course that is true.

What about making quality measurable? It is possible and under explored. In first case because nobody is clearly discribing measurable elements to check. Second because gedcom datastructure and contents doesn’t allow to perform this kind of checks. And third because the big genealogist databanks are not forced to do decent quality checks on the basis of measurable elements.

For starters I would like to read more about measurable elements when we talk about data quality and genealogy.

This happened to me, except because of someone ‘not paying close attention to extended family & I just attach them to my tree’, I found the part of my family that I have been searching for most of my life! And, yes, that’s exactly what she told me when I proved to her that they were my family & not hers! She still has them attached to her tree!! I’m in touch with my new found family & we are 100% positive we are family due to known family facts. I never attach anyone or any document to my tree unless I am 100% sure they/it belong on my tree. Why in the world do I want someone else’s family??? This was terribly upsetting to me & I was an emotional wreck for 2 weeks & I had the help of a professional, until we were absolutely certain this family was mine.

Amen. I am finding all but 2 trees out of 20+ have listed the wrong wife and now ancestry only returns that woman. A pox on ancestry for using our trees for “facts” when there is no fact to a lot of it. I hunt the trees. I’ve found good clues. I’ve also found a lot of garbage that tree owners will not fix. My grandparents did not have a child in Michigan who lived her entire life in Michigan. It’s not even possible for that child to be theirs in any way shape or form. And yet, there she remains. So beware anyone with Maria Ward from Michigan in their tree. She is not related to the rest of us.

I really like that findagrave has so many more linked families BUT people need to read what it says. If Jane Jones married Joe Smith she would not be Jane Somenoneelse unless she had married that person, too. Just because her name is Jane doesn’t make her the right Jane.

Awesome information! I have found what you have said to be true when copying from other’s ancestry, or from my own mistakes. Obviously some people don’t bother to check birthdates, etc. because it’s not reasonable to have a mother younger than a son. And I have found that…

Thank you for a great reminder and many “hints.”

What a shocking story and I do hope the child finds her real family one day. I can understand the point about her not being returned permanently to your first cousin, because I know that at five I would have been extremely traumatised if I’d been taken away from the only family I had ever known, BUT this does not mean there should be no contact with the birth father. He should have been brought into the child’s life somehow, as there is nothing traumatic about a child meeting other adults such as relatives and friends of the family in social situations. As for the birth certificate, it should absolutely reflect the biological parents of a child, otherwise it’s just nonsense. And in the case of families where there is an inherited illness, the lack of correct information could be life-threatening or could affect your choice whether to produce children yourself or not. For adoptions there should be an additional document to attach to it but certainly not to replace it. And in 21st century situations such as surrogacy, egg donation etc, the birth certificate should specify who is who quite clearly! It makes me very annoyed that in England now in the case of a lesbian couple both women can be recorded as mother, not from any moral considerations but because it is simply not scientifically true. Thank goodness for the family tree DNA website. There was an interesting case in my own family. My cousin Rex found and connected with his own paternal family on the site. His dad Henry was born out of wedlock in the 1920s and his grandmother refused to her dying day to tell him who the father was, but now Rex has discovered his grandfather’s identity, thanks to the descendants of his grandfather’s brother joining the site and they got second-cousin matches! Sadly this was too late for Henry who died before all this sort of specific DNA matching was invented, but at least Rex knows who his grandfather was. I suggest your cousin join the site just in case his daughter ever joins it too.

I am SO interested in what you said because my 1st cousin’s daughter was taken by a man who fradulently put his name on the baby’s birth certificate behind my cousin’s back, let the mother die 3 weeks after the birth by refusing to call emergency services when she stopped breathing ,& then sold my cousin’s daughter to a woman in another county (she got the little girl she always wanted & he got the baby’s Social Security checks) AND her corrupt judiciary friends in small town Arkansas facillitated her act by delaying hearings so my cousin could be claimed to not have had contact with his daughter, which allowed her to keep the baby “in the best interest of the child” because she’d become accustomed to the woman as her “mother” over the 5 year court ordeal. Even one of the 3 the appeals judges saw there was absolutely no reason to sever my cousin’s parental rights & stated in her scolding of her colleagues that the baby was given to this woman simply because she appeared to be “better” because she had more money than my cousin (who is no where near poor but not as well off as this woman is.)

My point in saying all that is to let you know that some parents didn’t give their children up, & some adopted children are actually victims of corrupt judiciary in corrupt towns where baby selling is more common than you’d think. (One judge in Arkansas was put away for heading one of these rings.) What angers me, both as a family member of this child & a genealogist, is how birth certificates of adopted children are allowed to be changed, reflecting the adoptive parents as birth parents! This is the one of the stupidest. most cruel decisions ever made in our legal system, because it wipes out the actual birth parents, as though they never existed, & puts people who are not blood in as if they gave birth to the child. Once the child grows up, if they are lied to their entire life, as my cousin’s daughter is being lied to, they have no idea there ever was another blood/DNA in them, until one day something happens & they get the shock of their life!

We have made sure enough information is on the internet so my cousin’s daughter will one day be able to find us & will see all the hearings & appeals, all the way to the US Supreme Court my cousin has filed, but many adoptees are not that lucky. This is really heartbreaking, as you cannot find your true heritage, your blood family’s health histories, or even who wanted you when perhaps you thought they had rejected you. These laws HAVE to change & I hope some of you adoptees can one day get together & start writing your Congressmen & Senators to make them aware how horrible these laws are for you.

I wish you peace of heart & hope someday all of you who are looking for your true heritage find it.

This is the same problem on my husbands side (Coleman Family) There were four brothers and three were well documented (Thomas , Michael and John) and the brother (James) was only visible in the 1800 census. Everyone was the three names above.

My husband’s side did not fit into the linage of the three brothers. I determined that he was most likely descended from James and found a few records, he rented instead of owning land. He has a Revolution WAr pension file that is empty. I honestly think someone took that file long ago

This had been a problem for twenty years. They were from Huntingdon County, PA

On adoptees: Please be very wary because most adoptees have an “adoptee” birth certificate with a court appointed (new) name which lists ADOPTIVE parents, not birth parents. We adoptees aren’t so easy to ‘document’, and if abandoned, there is a huge probability that our birth was not in the state in which the certification is created (this usually by the judge presiding over the final adoption).

In some states there may be a notation that says the child was born ‘in the continental United States’-which by the way will instantly deny you a US Passport for lack of city -county- state- country format required, no ifs, ands or buts, and NO exceptions to this rule) which is a red flag that alerts the observer the person named therein was not born in the state which finalized the adoption.

What will be missing for 99.99999 % of adoptees, besides their actual parentage, is information regarding other close family (grandparents, great grandparents, and siblings) which I am always amazed that most so-called researchers don’t even consider, just as they don’t consider the existence of half-sibs from other relations between their parents and later partners-unless those sibs pop out of the woodwork via a DNA match-shocking them as much as it may shock the adoptee-who also rarely considered other family beyond the parents who went missing early on in their lives.

Beware of the myth that information on documents is correct, or that information on web sites are absolutely beyond reproach. Any information from a human is suspect, particularly those so-called infallible census forms, because they are, in reality, one of the worst documents to rely on for accuracy. Other ‘official’ documents can be equally misleading because they are inaccurate-or just simply false. As someone has already noted, Find-a-Grave is one of the worst avenues for unearthing (no pun intended) accurate information. Even the headstones themselves can mislead.

For adoptees, the best advice I can give is to disregard with a grain of salt anything your adoptive parents may say about your birth parents*, including what social service agents may say because too often it is either simply speculation, or worse, gossip. Those intending to abandon a child -or even any parent-didn’t then nor does now carry a child’s birth certificate with them, just as very few carry a marriage certificate around on their travels. *Except when you discover that your ‘mother’ is in reality your grandmother or an aunt-or vice versa.

It is an asset to know history-of the era in which you (or the subject) is born, and of the ancient world. But remember that history, any history, is first observed by someone with his/her own perspective or understanding of a given event or events. Someone else’s may be entirely different; only later is it written down. But generally speaking, a knowledge of history will be a great help in resolving questions about authenticity; again, authenticity says an event occurred, but it does not necessarily tell the true circumstances.

Lastly, be circumspect about playing the expert or being so very certain that only you know this, that, or the other. You are neither perfect, nor are you party to what is true or not true about anyone, not even yourself. And don’t be arrogant to think you will tell another’s story better than they. As a paraphrase of a Benjamin Franklin remark, “An ounce of pretention is worth a pound of manure.” made quite famous in the film Steel Magnolias. Franklin’s words were ‘prevention’ and ‘cure’, which also is good for anyone reaching family or other.

I have found my own great grandmother under Catherine, Bridget, Della, & Dee. It makes researching her VERY hard ????

It is a judgement call for spelling and dates. You have to use all sources available and double check everything.

I have a great grandmother who we couldn’t find, online or by snail mail. Turns out the spelling of her maiden name was wrong. I was showing my tree progress to my Mom and she muttered under her breath a different name.

When I entered it, her death certificate came right up. She had died 20+ years after people thought she did. Turns out one son, who never said a word to the rest of the family about it, knew where she was the whole time and gave the info on her death certificate.

We were able to fill in a huge branch of the tree from Mom muttering under her breath.

On the other side of this issue, I have had people reach out who found errors on my tree. They were extremely kind, and in one case, contacted me a second time thinking I hadn’t fixed it. Turns out I had been ill and not getting any messages. He was very gracious and helpful. We both have a common generation that is extremely hard to trace and has kept me updated with new research he has found.

I have learned tons after making many mistakes!

Happy Family Hunting! Enjoy and check, check your sources.

I am not interested because I have to pay this service !

So, many thanks to you, but if it is free, I agree to receive my dates of ancestors an location, and profession, etc.

This article is on target! When I began my research, I located a tree that listed my branch as belonging to one of the original 3 brothers sons & not the brother who was my own ancestor. Because all 3 brothers had sons of the same name, & this error occurred in the 1700’s, it wasn’t until I could thoroughly examine the 1790-1840 census records to match the ages of family members in each of the households of the same name to straighten out the mess this one researcher had created. It took a long time of tedious attention to detail but it was worth the effort, as I now have my own census (& land records) confirmation of which Jacob is which, & can know what I have on my own tree is indeed accurate. Never ever take any information anyone has on their trees as fact unless you know the integrity of the tree owner or have confirmed the information yourself. Even now I see so many who find a name on a census across the country from where the person lived their entire life & post it as “fact” that others inadvertantly re-list. Confirm everything!!

That’s exactly my thinking! I think a daughter had him “out of wedlock” and they gave him the Rodgers name. But the fact that my GF named the mother as Mary Baker instead of Rebecca, makes me wonder. I don’t know the chikdren of her first marriage except the well documented Samuel Baker Fish. But seems like then the mother’s name would’ve been Fish instead of Baker. If it was an older daughter of John and Rebecca Baker Rodgers that had a baby, then the Rodgers name would’ve been correct, and they gave the mother the Baker name. I just don’t know!! Maybe I’m putting too much faith in my grandfather that he didn’t just get the names wrong because he wasn’t a stupid man, lived with my GGparents for 10 years, and Rebecca was still living when my GGparents married in 1880. She died in 1883. So my GGMother would have known her. Surely someone could’ve told my GF the correct info!! He didn’t pull the name Baker out of his butt!!

I’ve seen a couple of times where the teenage daughter actually had the child but her mother claims the baby as her own from then on and raises the baby as such. I’ve even seen a birth record doctored to reflect it. Jack Nicholson was an adult before he realized his older sister was actually his mother. Just a thought.

Yes, I agree. I’ve seen many inaccurate info on DCs and findagrave. My problem with my GGF’s DC is that my GF, his son-in-law, was the informant. This was in KY in 1917. But my GF and GM married in 1907, and lived with her parents for the 10 years before my GGF died. I would’ve thought he would’ve known the man pretty well after 10 years, and his wife and mother-in-law were alive to give the correct information if he didn’t know it. So either he was totally wrong, or the couple my GGF lived with were his grandparents. He got the last names right, but the first names were way off. And the couple he lived with would’ve both been around 50 when he was born. I’m DNA matched to descendants of the other children in their household though. But the so-called “census mother” he lived with had grandchildren from her first marriage living with her who weren’t but a couple years younger than my GGF. I have no choice but to say they were his parents even though my gut says otherwise. I have no way to prove or disprove it.

Certificates are only as accurate as those who gave the information and the clerk who wrote it down. Especially in stressful times, as in deaths, it is easy to give out incorrect information, and clerks did not have the time (or interest) to double check what someone said. The same goes for tombstones and censuses and other information sources… they are as accurate as the person giving the information at the time. And it always makes me laugh that, not so many years ago, the GROOM was asked for family information, such as mother of the bride’s maiden name! Not the best choice. I have even found birth certificates where the mother’s name was “Unknown”. I can understand that possibility for the father, but the MOTHER??

That’s not boring, it’s rather interesting! At least you got some of them back. I only own one of my family’s memorials, only because the owner simply passed it on to me without ever discussing it – not that I minded. As for the others I am happy to let them be managed by someone else, as long as that person is active and does make corrections if I send them in.

Yeah, I’m a contributor myself. I try to get my family memorials transferred to me. Some contributors just want to have the most memorials instead of caring about accuracy. I’m about to bore you with the story of how I gave one contributor who lived in the area where my family cemeteries were located on private property no longer owned by anyone in my family. He took pics, made the memorials, etc. I even paid for clean up of one of the cemeteries. I spent a couple years working with him on all kinds of memorials of my family members, via email, all over the area where he lived because I live in FL, but from eastern KY. He had some kind of mental breakdown, I don’t know the details, but he transferred ALL of his memorials, even my family, that we’d worked on together, to some contributor that I didn’t even know. I was LIVID to say the least. He said I didn’t seem interested. What?? Because I was in the middle of moving!! I didn’t know he was giving away his thousands of memorials at the time. Holy crap!! I did contact the person and get some of my family’s memorials.

The best thing is to sign up to findagrave yourself, and then you can make edits to anything wrong, subject to the approval of whoever put that grave on the site in the first place. If they care about accuracy they will then get your corrections in. It is free to be a member. What you have to remember is that the person who puts a grave onto the site is usually one of the huge band of people whose hobby it is to voluntarily photograph and record graves all around the world, and are no relation to the persons on them at all. The reason I joined in the first place was in order to upload photographs of my relatives, and doing this does not need the approval of the manager so your photo will appear straight away. I always think it’s nice to have a photo there along with the grave.

I agree with you about Find-a-grave as an unreliable “source”. My own Grandfather’s family have been linked into someone else’s family and the person never responded to my message or altered it. Hey ho happens all the time on Ancestry too when I contact people to tell them that they have the wrong data. I’ve given up doing that now, I just sit and shake my head instead.

I hope that folk tell me if they think I have my information inaccurate! We can all make mistakes.

Excellent article. I have been doing family research since 1991 and have seen this happen to other people and it even happened to me once with almost identical father/mother/ children’s names and very close DOB’s – luckily ,in a moment of clarity, I discovered the mistake early because it was getting me way off track.

I am coming late to this discussion but need to add that even government records can be wrong, and many times are. There are typo’s which have never been corrected, misspellings, and people giving information that accidentally is incorrect, intentionally incorrect, or they just don’t know, and felt they had to give something when asked. Even headstones can be wrong with both names and dates when it comes to spellings. I too am a person who keeps my tree private until I know beyond a shadow of a doubt that most, but hopefully all, the information is verified to the very best of my knowledge. Be careful too because this is still going on today. I am highly sensitive to government agencies such as Social Security, I know this happens, and I know it isn’t going to get fixed by even going in repeatedly with documentation proving to them its wrong. A regular worker can’t change information once its entered into the system; it takes a higher up, and in order to get to a higher up it takes a stroke of luck, but as in my case a tantrum to get someone to listen, at closing time, when we were the last ones in the agency. (They had put my son in the computer as being dead, instead of his Dad; and they didn’t even have the same first names) It too me a constant 9 horrific months to get it changed. One would think that government documents would be accurate but they really aren’t. Even with death certificates. I have 4 great uncles on my Dad’s side, and they all have different father’s listed on their death certificates. I never met them but have written names passed down via a family history, but also they are in each other’s wills; it’s just that whoever was their survivors either didn’t know, or when they came to the US they came with someone else. The households are cross referenced on US Census with family members living with each other, but again, one would think they would have some continuity, which might explain why I can’t find the one sibling who was last heard from in 1850. Sorry to go on so long here, but with me a minimum of 3 pieces of verifiable documentation with the same information on it, is needed to consider a person valid. I just ask that you be leery of government agency records also. Even with family members I have known, I have found many errors., mostly typo’s, but still many errors.

You can’t always refute that. You can only go forward making sure that the information that you add to your tree is thoroughly documented. As you say, they thought it was truth. I am not sure any family history book can be 100% complete because the tree is always growing and ‘missing pieces’ get resolved over time. As a researcher, we are often up against another person’s memory or their take on the facts. You don’t say if the book was written in the 1800s, 1900s or more recently. Bottom line, it’s less stressful to simply enjoy our hobby rather than worry about correcting others. In time, you can share what you’ve found – primary, derived primary and secondary sources and documentation included – and let them make up their own minds.

In my haste I did not edit my spelling, I meant reading. My tablet is small and hard to type on.

I have been teading peoples comments and feel compelled to say something. My tree is on Ancestry. It is definitely a work in progress, especially since I did my DNA. Much of what my so called family thought was truth is in fact, fiction. They even had the nerve to publish a book without representing the entire family. Boy is it wrong in so many ways. This was written pre DNA and blindly omitting actual family Ancestors. There are unusual circumstances involved, ie: an Indenturement. Our branch has the court issued documents. There are missing pieces. Much of the recopied over and over family tree is based on erroneous facts from a Published book. How do you refute that???

I also try to correct errors I see on-line. As you say, most people claim they are right, even with solid evidence, or do not care at all.

I had a guy insist to me that my Grandmother’s middle wasn’t Mable. He told me her middle name was Maple. Best thing is that had NEVER ever met her.

In her first marriage to Jeremiah Fish in Belmont Co, OH her name was Rebecca. In her 1828 marriage to John Rodgers her name is Rebecca. And on all census records and her burial record. But that was a good thought!

Sally, is there a chance her name was Mary Rebecca and she chose to go by Rebecca. I have been doing my genealogy for 20 years and have found several females that chose to use middle names but on official forms used first name. On some took me years to discover this, on others just days as they still had living family to set me straight.

Thanks. I sort of thought that, but wasn’t sure if I should surrender to what everyone else says, without any proof besides census records, or stick with my gut. I’ve just run out of avenues to go down to find the smoking gun to prove or disprove anything.

When I had an obviously missing generation I added it between the son and grandfather and called it “unknown surname”. It kept that spot open and I did find the missing couple.

I really don’t like that they have linked findagrave memorials as a “source” when many are not accurate at all. But then many trees aren’t accurate either, so I guess it’s no different. I had a findagrave contributor say my grandmother was the spouse of my uncle because they shared a headstone. My uncle’s widow had remarried and gave my dad the grave for my grandmother. I liked to never got her to unlink them or transfer the memorials to me.

OK, this is off topic, but I have a question for y’all. What do you do in your tree if a generation is missing? This is my problem: My great-grandfather, James Rodgers, died in 1917. He was my grandmother’s father. My grandmother and grandfather married in 1907, and lived with her parents for 10 years before my GGF’s death. My Great grandmother continued to live with my grandparents until her death. My grandfather was the informant on James’ death cert. He names his parents as James Rodgers and Mary Baker. I have looked for them without success for 15 years. I had some census records in my ancestry shoebox for someone the correct age for James, but he lived with a John and Rebecca Rodgers. Then I had my DNA done, and was matched with several descendants of John and Rebecca, and indeed Rebecca was a Baker. But my gut tells me she is his grandmother, not mother. She would’ve been 50 when he was born, and she had grandchildren from her first marriage living with her. I’ve never been matched with any other Rodgers except her direct descendants, but tons of Bakers going back to the 1700s. If it weren’t for the DC, just based on census records, I would call them his parents, but something just won’t let me. How would my GF gotten the names so very wrong? Remember, he lived with the man for 10 years, so I would think he’d know him pretty well. James’ wife and daughter were alive to give him the correct information if he didn’t know it. Others have him as John and Rebecca’s son, and some even have a note that the DC informant wasn’t reliable. I’ve even gotten the wills and obits of any children of John and Rebecca I can find. None name James as a sibling, but then they had a couple other siblings that weren’t named. My grandmother lived with us until she died when I was 11. She never mentioned or visited any cousins, and his so-called siblings lived in the same area, but I was a child, so maybe I just don’t remember. I am for sure without a doubt descended from Rebecca by DNA. So, what would you do? Say John and Rebecca are his parents? I can’t skip a generation in my tree. Do I just let it go, and say my GF was mistaken? I just find that so hard to believe when he lived with the man. I can see getting James and John mixed up, but Mary and Rebecca aren’t even close. Sorry for getting off topic, but since y’all are experienced genealogists, I just wondered how you’d handle it. Thanks!

Very good advice and comments. I keep my tree private because as others have said, it’s a work in progress, and I have spent years of time and money on research. Now, if someone asks, and I can see a genuine connection, I happily share information, and invite them to my tree if they ask. But if someone is a DNA match as a very distant cousin with only moderate confidence, I politely refuse, especially if I look at their tree and see no common surnames. And I do send people messages on ancestry who have the wrong information. I have found that people either don’t like to be corrected, or don’t care, because I rarely get reply back, and I’m not rude about it. And I I never copy trees. I do use some for names I can research, etc. but the stupid entries as mentioned above drive me crazy! I can’t get any further back on my 3rd GGF’s line, and I found someone who had this whole lineage for him. Yeah, sounds great, except the people they had for his parents were born and died in SC, as did all the siblings listed, yet somehow my 3rd GGF was born in VA in 1764. Use some common sense!

hello H.A Bird. I am also a Byrd which was spelled Bird until late 1800’s and changed by my great grandfather which I never knew until starting ancestry. I have had the hardest time finding this family. Who knows you and I could be related ; )

“The whole point of joining a site like ancestry, surely, is to share information freely.”

Ancestry.com is an invaluable site with billions of records to search.

Copying others’ trees is not research. Research is discovering primary, derived primary and secondary sources and determining how / if they fit into your family tree.

I’ve spent a lot of years, driven a lot of miles and spent a lot of money to get ‘my’ research where it is today. Others can ask me what they want to know (nicely) but I am not going to pay Ancestry’s subscription costs AND supply their other paying customers with a ready-made tree.

Genealogical research has been around a lot longer than the internet and before Ancestry[dot]com. It’s never been easier for people to research their ancestry. If I were to have copied what others have copied, I’d leave my tree settings to public also. Researchers have a right to choose the settings they want for their own work. That’s why there are choices and that’s why there is a option to contact that person.

Certainly don’t mean to offend any individual, but everyone knows that clueless people are around in every walk of life including ancestry research. I would never tell any individual this, but always write most politely and helpfully whenever I find an error and 90% of them write back to thank me., and I have made online friends with many new cousins this way, too. I find some mistakes very amusing e.g. I have a lovely cousin who is nevertheless not too bright and in some places on his tree he has got a married couple with 20 or more children because somehow he has got the exact same kid duplicated or even triplicated! He has gladly made me an editor so that I can correct his mistakes myself so he doesn’t have to. I do also understand many mistakes are simply beginner’s error, of course I make allowances and don’t judge anybody because I used to make the same errors myself. I certainly don’t look down on people who make mistakes, which I can see are made by people enthusiastically clicking on an exciting looking link. I certainly didn’t realise when I first started out that some “hints” are really wrong, i.e. the ancestry software is only for clues and not foolproof. (I think they should tell newcomers this, to stop them getting carried away) But now I think it is fair to say after 15 years or so that I do not put out any mistakes onto my own trees.

Hi Theresa. I have to take issue with your comments here. On the one hand you’re saying someone is a “dump idiot” for “blindly copying” details from someone’s tree and then your saying “what’s the point of lots of people doing the same research” I don’t think you can have it both ways. Are you really 100% certain that you haven’t made a single error on your tree which could lead to more blind copying?

A good researcher will always where possible check and verify everything they are adding to their own tree. You then have to make a personal choice whether you accept someone else’s research or not. Experience is another thing to consider. As with any hobby you improve and get better with time and we need to make allowances for this. I really don’t think slinging insults helps anyone.

That’s a good point, keeping it private whilst a work in progress. I get around that by for example putting question marks after names, “ABT” in front of dates, and often writing “speculative guess re date” in the info box under an event because it is often worthwhile assuming, say, that a girl marries at 21, working her birthday back from that, and indeed guessing a birthday in this way often produces a flood of good results. My tree is a permanent work in progress and I check as carefully as I can before adding anything, so if it were private now I would never get it out into the public domain as it is never going to be “finished”! Also I write to almost everyone who I notice is making a mistake, e.g. finding a matching tree containing an ancestor of mine who does not belong there. I write very politely of course, and contrary to what many commenters have said, most people are very grateful to be told, after all, don’t we all want to be as accurate as possible.

That’s a good point, keeping it private whilst a work in progress. I get around that by for example putting question marks after names, “ABT” in front of dates, and often writing “speculative guess re date” in the info box under an event because it is often worthwhile assuming, say, that a girl marries at 21, working her birthday back from that, and indeed guessing a birthday in this way often produces a flood of good results. My tree is a permanent work in progress and I check as carefully as I can before adding anything, so if it were private now I would never get it out into the public domain as it is never going to be “finished”! Also I write to almost everyone who I notice is making a mistake, e.g. finding a matching tree containing an ancestor of mine who does not belong there. I write very politely of course, and contrary to what many commenters have said, most people are very grateful to be told, after all, don’t we all want to be as accurate as possible.

Like Virginia, I keep my tree private while I’m checking sources or working on new branches. I’m always happy to allow people to view my tree if there seems to be a connection, but always with a request to alert me to errors.

Hi Teresa!

I can’t speak for everyone on this, but I keep my work on Ancestry private and unsearchable because those trees are works in progress and I feel it’s irresponsible to publish work for the public to see if it’s not at least somewhat accurate. My ancestry trees are where I am free to make those mistakes and go back and correct them without the worry that I may be presenting those mistakes as facts.

I always check the scanned image of a census, not just the transcription, as the transcribers make many mistakes. In one case, a couple of aunts were wrongly transcribed as the daughters of a Lord, whose estate they lived on, and whose big house was next on the list to their cottage! I have also spent many hours taking the trouble to send messages to people whose mistakes I find. I think one problem is that some people are just dumb. I always remember where one tree which came up as a hint on ancestry showed a man having a father who was dead 20 years before the man was born. i wrote to the owner of the tree and politely pointed out this impossibility, when I was dying to say what an idiot he was for just not noticing such a piece of nonsense and blindly copying it.

I cannot understand why people above are saying people who copy their work are “greedy”. The whole point of joining a site like ancestry, surely, is to share information freely. After all, what is the point of lots of people doing the same bit of research when one of us has done it already? I love it when I see people using my photos and so on which I have put out there. I always wondered why people had private trees when living people are private anyway and the dead are not around to care, and here I have had some answers, and I am distinctly unimpressed as it goes against the whole spirit of ancestry research being a fun shared enterprise.

Have a fun time seeing some trees where the same person is entered more than once, or has multiple marriages.

Also on my GG Grandparents census, both around 60 years old stated that their youngest son was 5 1/2 months old!!!, when in.fact wad their grandson. Wayward daughter lol.

I whole heartily agree, if you are not sure of a connection, the keep it to your self.

I adhore people who say ” I can trace my tree back to ?” I always say unless you can prove it by a paper trail for example, then where are you getting your Facts from! All my tree is documented, by authentic documents or related family facts. I would love to go past the points I that I am at, but will not say for sure, unless I am sure.

I have had people trying to link my tree to people in other countries, when I know that my relations, never went there. I am now going to make my tree ‘private’, and if anybody thinks they are related, the contact after you are sure.

.A couple of my biggest complaints Some people just don’t “think”. How could someone live in say Texas in the 1400’s? I’ve see this in a tree. It’s amazing what some people just copy along without thinking.

My grandfather’s death certificate has the wrong first name for his father, and his brother’s death certificate has the wrong maiden name for their mother. The marriage certificate for their parents has the correct information, and their mother’s Civil War pension application confirms everyone’s names.

The information on Find-a-Grave isn’t always correct either. Dates on grave stones can be wrong, as well as names. For example, one of our family headstones shows my grandmother’s sister as Elizabeth E, while her name was actually Emma Elizabeth. Another sister was named Sarah Helena but the grave calls her Helena S. Half the people in that family went by their middle name.

So very true. I have an ancestor where someone attached a document “proving” he fought in the War of 1812. The man died in 1761.

I find mistakes all the time. Even found mistakes in a couple of books. It’s hard to find the information you need sometimes. When Ancestry puts documents to link with no picture of the document. I like to use the hand written documents wherever I can. They do get hard to read sometimes. The most annoying thing is when someone writes to you and you answer them clearly, then they write back again asking you the same question. Or someone just asking a question so you end up doing there work for them. Like I have the time to do there tree. I try my best to get it right. I use Google a lot too, for older than 1600 records. I find Ancestry lacks information about the Welsh ancestors. The UK has some good sources.

Most of the documents I’ve sent for were in the $25 range. Occasionally they were $1 per page. Occasionally they sent them email for about $1. And a lot of the same documents I’ve paid for are now available on line for “free” once you’ve paid your subscription fee. I’ve had the best luck asking for copies from the courthouse. But you do need to know the date and location. Nobody has time to read through the books for you unless you hire them to do it.

Not always so. The last batch of birth and death certificates I requested were $1 each. A marriage record was 25 cents (price for printing the page). The batch was at the town clerk level and the copy of the marriage record was at the county level in two different states. You can also request a non-certified copy or a ‘genealogical copy’ at some repositories. Researching where the records are kept is just as important as researching the family members.

My trees are all private and for the reasons up and down this page. The thing about making it private is those willing to put forth the effort and interested enough will contact you…..allowing you to meet a new cousin in process.

My husband’s cousin was adamant that her grandmother had only had one daughter and a number of sons. On further digging she eventually worked out that in addition to the 2 daughters I had found, there were in fact another 2. All had died in infancy. This was a family she had grown up in and nobody had ever known about these lost little girls.

Depends on the program you use, but usually there’s an “unattached” option…

How do disconnect someone you mistakenly added?

I have seen so many no-brainer mistakes on public family trees, such as sons born before their fathers and photographs of people who lived in the 1600s.

I have the same thing on my Siekbert family tree some person on Ancestry decided to give my grandmother an extra son you know I knew all my aunts and uncles and this person was never in our family I left a message for the person letting them know they copied my tree and then added a person that does not exist in my family but they didn’t bother to change it

I think we need to be careful making assumptions and comments about greed. Yes we all want things to be correct but perhaps the fault here lies with programs that allow huge chunks of information to be copied in the first place. I hate Ancestry tree links as if your not careful it will add in other people’s errors without you realising it. Further to this perhaps the problem is that once a large section of tree is copied it is not exactly easy to undo to correct. There is one simply lesson here. NEVER copy other people’s trees unless you have first researched it to ensure it is correct. Furthermore I would suggest adding people one at a time instead of taking or copying whole branches.

Good article and responses. I guess we have all had similar experiences making our own mistakes and having others consider cut and paste as a reasonable genealogical tool. But one issue I don’t see mentioned is that paternity is not 100% proven even with good documentation. For example, there was an old family story told by my late father that his paternal grandfather, James, was an orphan and had been “adopted” by people who had my father’s surname, Short, and that his real surname was Rose. In my research I found James’ actual birth record from 1853 and his actual death record, not indexes. His parents were listed as Daniel and Dianah Short, not Rose. I told Dad he must have been mistaken. After my father died, I had a 1st cousin take a YDNA test that didn’t have a single Short match, but many Rose matches. After much work and subsequent autosomal DNA matches, I found that Dianah was the mother, but James’ father was James Rose, also married to someone else. Dianah and her husband, Daniel, during over 12 years of marriage had never had children. My lesson was you even have to question the written documents. I will always regret my father died before I could tell him he was correct. James was only one of several ancestors who were born out of wedlock.

I also have met some new cousins through these online sites. So it can be a great help. One was from Australia, and she has come to visit in Canada twice. The newest one is from France. We have just started to write. I love having cousins write from the US that I knew must be there, but now write to me and we feel like we know each other.

Just a reminder to Always be careful to check your sources, and read the documents carefully. I have actual birth certificates of my grandmothers and copies of the original of her sisters and the date was recorded incorrectly for her birth by the clerk and not caught by her father. Two different years on the same paper. It would make her be born only 2 weeks after her older sister. Grandma tried to get the govt. to correct the error years later, and they requested $3.00 to change the document for her. She was outraged that she should pay for their mistake and decided to let it stay as it was. So she and my aunt are still registered as born 1907 and only a couple of weeks apart. I knew they were not the twins that were born to my Gr-grandma. But another researcher might not be so lucky.

I’m trying to get a tree changed for exactly that reason. She won’t. And worse yet, now that person in her tree is an orphan because she certainly doesn’t belong to my grandparents. I would think the tree owner would want her with her rightful family but I guess not.