U.S. census records are a critically important part of just about any genealogical project – at least those involving ancestors who lived in the United States between 1790 and 1950. But, as with other sources, information noted in a census record can’t always be taken at face value.

Despite how valuable these records have become to researchers, they were not created for this purpose. For this reason we need to try to understand everything we can about this go-to resource if we are to walk away with the most accurate data available.

These 9 Surprising Facts Will Help You Get the Most from Your U.S. Census Research

Understanding the nuances of U.S. enumerations can help you put your ancestors’ information into context, make sense of confusions and dig up new details.

1. The Guidance Given to Census Takers Can Change the Meaning of Data You Find About Your Ancestors

In the early decades, U.S. Marshals and their designated assistants were tasked with collecting information in their assigned areas but they received limited training or guidance. Many recorded data how they saw fit, with little oversight. In fact, workers weren’t even provided pre-printed forms until 1830.

In later years, however, instructions to enumerators were very specific – growing seemingly more so as each decade passed. Reading through these instructions can provide a wealth of insight into how and why information was recorded the way it was.

It can even help you solve confusions you have encountered, such as conflicting ages or birth places, since what was actually recorded may not align with what we expect was recorded (you’ll find examples of this as we move through this article).

We cover this topic in depth in our article, This Information Will Make You Question Every Census Record You’ve Ever Collected. You can also find the instructions to enumerators for every year, beginning with 1790, on the census.gov site.

2. Information Provided Was “As Of” the Official Enumeration Date, Not the Date the Census Was Taken

As noted in our reference guide to the U.S. census, each census had an official enumeration date and all information collected was to be based on that date (as opposed to collecting information based on the actual date the data was collected).

For example, if the official enumeration date for the census was June 1, the age of a family member provided to an enumerator on, say, August 15 would have been the age of the person on June 1, not August 15. And, if a person had passed away after June 1, they would still be listed as living.

You can see how important this minor distinction can be. Noting the enumeration date in your documentation will give you a more accurate view of the information you are collecting and will help you adjust ages and other facts accordingly.

See the official enumeration date for each census in our U.S. Census Quick Reference Guide.

3. 1890 is Not the Only Partial Census

The 1890 is famously – and frustratingly – missing a majority of the year’s enumeration due to fire, smoke and water damage but – did you know – portions of the 1790, 1800, 1810, 1820, and 1830 census records are missing, too?

Every single one of these enumerations experienced some significant loss so, before you determine that your ancestor must have moved out of an area because they’re not showing up in a census search, you may want to look for them in other records created in that place first. See the census guide for what states were lost in each year.

4. Occupations May Not Be What They Seem

The enumerator’s instructions offered guidance on exactly what was to be considered “work” and how a person’s occupation was to be recorded.

The 1860 census instructions, for instance, dictated that a person who employed others was to be “termed differently from the one employed.” So a mechanic who employed other mechanics, or a carpenter who employed others would be listed as a “master mechanic” or “master carpenter,” while his employees would be listed simply as “mechanic” or “carpenter.”

As we explain here, enumerators for the 1930 census were instructed to record the “occupation in which last regularly employed” (even if that employment was in the past), which means that your family member may have been listed as a “plumber” by trade, but might not have worked in that capacity for years.

This description was even more tricky for women, as enumerators were given specific guidelines like these:

“A woman who works only occasionally, or only a short time each day at outdoor farm or garden work, or in the dairy, or in caring for livestock or poultry should not be returned as a farm laborer; but for a woman who works regularly and most of the time at such work, the return in column 25 should be farm laborer. Of course, a woman who herself operates or runs a farm or plantation should be reported as a farmer and not as a farm laborer.”

This means that even if your great-grandmother toiled in the fields day after day, she might still be listed as a housewife, or unemployed – but if a man hadn’t worked at all in the past decade, his previous occupation is often still listed. Hmmmm…..Details like this definitely make you remember how important it is to dig deeper to find facts about your female relatives. You can find help for that in this article.

Understanding the requirements for census takers in the year an occupation was listed (as well as the codes and abbreviations common to that decade) can go a long way to better understanding what your ancestor really did for a living.

5. The Informant Wasn’t Always a Family Member

Section 10 of the enumerator instructions for the 1850 census states that information should be obtained by “some member of each family, if any one can be found capable of giving information.” However, if a “capable” person wasn’t available, the information was procured from “an agent of such family.”

This could be a neighbor, employer, friend…you name it, and may help to explain some of the wide-ranging ages and spelling of names from census to census. How well would you do if you provided this information for your next-door neighbor?

Of course, most informants probably meant well. After all, if a person was found to purposely give false information to a Marshal or his assistant, the informant could be fined thirty dollars “to be sued for and recovered in an action of debt” by the United States government.

The 1940 census is the only year that makes the informant clear. In other years, we can only guess. You can read about that in Mysterious Circled Xs, Cryptic Codes and Other Confusing Details in the Census Explained.

6. Those Listed Near Each Other on the Census Weren’t Necessarily Neighbors

Although some census years do show an address for each person, census takers in earlier years were often only instructed to number households and families in the order they were visited – not in any particular geographic order or by street address number. For this reason, he or she may visit several families on one road one day, then return the next to visit with the ones he missed – filling in other streets or areas in the meantime.

Although we genealogists usually pay close attention to the neighbors of our ancestors, we should be careful not to put too much emphasis on the fact that two families are listed concurrently, as it is entirely possible that they never lived very near each other at all.

Despite this, there were many instances where the order of visitation was very specific – and this influenced the order of families as well. Contrary to the earlier, mostly rural, censuses described above – census takers canvassing cities with blocks were instructed to canvass the city “one block or square” at a time starting at one corner, continuing in a clockwise manner, and returning to the starting corner before moving to the next block.

This explains why some census records will show three families on Wood Avenue, then two on Tuscaloosa Street, then three on Seminary Street, two on Military Road, then pick up again on Wood Avenue.

The lesson here is that there is often no way to know for sure what order households were recorded in, so we must be careful in making assumptions about how two households may have been connected to one another. To find out which census years contain an address to help you verify who actually was a neighbor, look to our quick reference census guide.

7. Shifting Boundaries and New States May Have Changed Places of Birth

Your ancestors who were born in the United States were asked to provide their state of birth in many census years. But a key thing to understand is that states were listed as they were currently known at the time of the census, which isn’t necessarily the same name that was used when your ancestor was born.

An example provided in the 1930 census instructions was, “A person born in what is now West Virginia, North Dakota, South Dakota, or Oklahoma should be so reported, although at the time of his birth the particular region may have had a different name.”

This could explain why some ancestors, especially those who lived in the 18th and 19th centuries, reported their birth states differently in different years. Pay attention to shifting boundaries, new states, and how information was recorded to help you solve these mysteries.

8. “Usual Place of Abode” is a Tricky Question

Census instructions cautioned against reporting individuals twice or not reporting them at all, but left the definition of “usual place of abode” to the judgment of the enumerator in many years.

If your ancestors was away at school, a temporary boarder in a hotel, a sailor or canal man, at a country home, or in the hospital, they were often (depending on the census year) enumerated as living with their families at their permanent home or added to the institution’s enumeration with a note about their true home written in the margin. If they had no other home, they were enumerated at the institution.

If someone is curiously missing from a family’s household, it may be worthwhile to consult a census index to determine if they were temporarily away and enumerated elsewhere. Discover more information about how to find missing individuals in the census in this article.

9. You May Be Misunderstanding the Meaning of Deaf and Dumb, Blind, Insane, Idiotic, Pauper, or Convict

If you ever find a notation like this for one of your ancestors, remember that those definitions may have meant something different at the time they were recorded. It’s definitely worth your time to review the instructions and definitions for this column, like these from the 1860 census:

The various degrees of insanity often create a doubt as to the propriety of thus classifying individuals, and demands the exercise of discretion. A person may be reputed erratic on some subject, but if competent to manage his or her business affairs without manifesting any symptoms of insanity to an ordinary observer, such person should not be recorded as insane. […] As a general rule, the term Insanity applies to individuals who have once possessed mental faculties which have become impaired whereas Idiocy applies to persons who have never possessed vigorous mental faculties, but from their birth have manifested aberration. […] In the case of insane persons, you will write […] the cause of such insanity […] as intemperance, spiritualism, grief, affliction, hereditary, misfortune, etc. Nearly every case of insanity can be traced to some known cause.

The 1880 census even included detailed supplemental schedules expanding on those citizens defined as such – you can read more about that and find out how to access those records in this article.

A Final Tip: Pay Attention to Every Single Detail in the Census

While we are generally looking for details such as family relationships, ages and places of birth when we search for our ancestors in a census, there is much more to be learned. As the examples above illustrate, paying attention to the details will often yield you great returns in the amount and accuracy of the data you collect.

When you examine these records closely, you might find additional information you never noticed before – such as the year of someone’s marriage, a clue to additional information on a supplemental schedule (like a farm schedule in 1910 or veteran’s schedule in 1890), a marked box noting that a man’s voting rights had been stripped (1870), whether your ancestor owned a radio (1930) or an entire row of new clues.

Paying attention to every detail could mean adding fascinating facts to your family’s story. But that’s only half the work – educating yourself about how and why this information was collected means truly understanding the facts as they were meant to be understood.

Read our U.S. Census Guide for help determining what information can be found in each census year (it also includes an easy to reference chart) and take the time to review the instructions given to census takers to make sure you’re reading the census correctly.

You Might Also Enjoy:

Why You Should Never Rely on “Facts” You Find in the Census, and What to Do Instead

By Patricia Hartley. For nearly 30 years Patricia has researched and written about the ancestry and/or descendancy of her personal family lines, those of her extended family and friends, and of historical figures in her community. After earning a B.S. in Professional Writing and English and an M.A. in English from the University of North Alabama in Florence, Alabama, she completed an M.A. in Public Relations/Mass Communications from Kent State University. She’s a member of the Alabama Genealogical Society, Association of Professional Genealogists, National Genealogical Society, International Society of Family History Writers, Tennessee Valley Genealogical Society, Natchez Trace Genealogical Society and the International Institute for Reminiscence and Life Review.

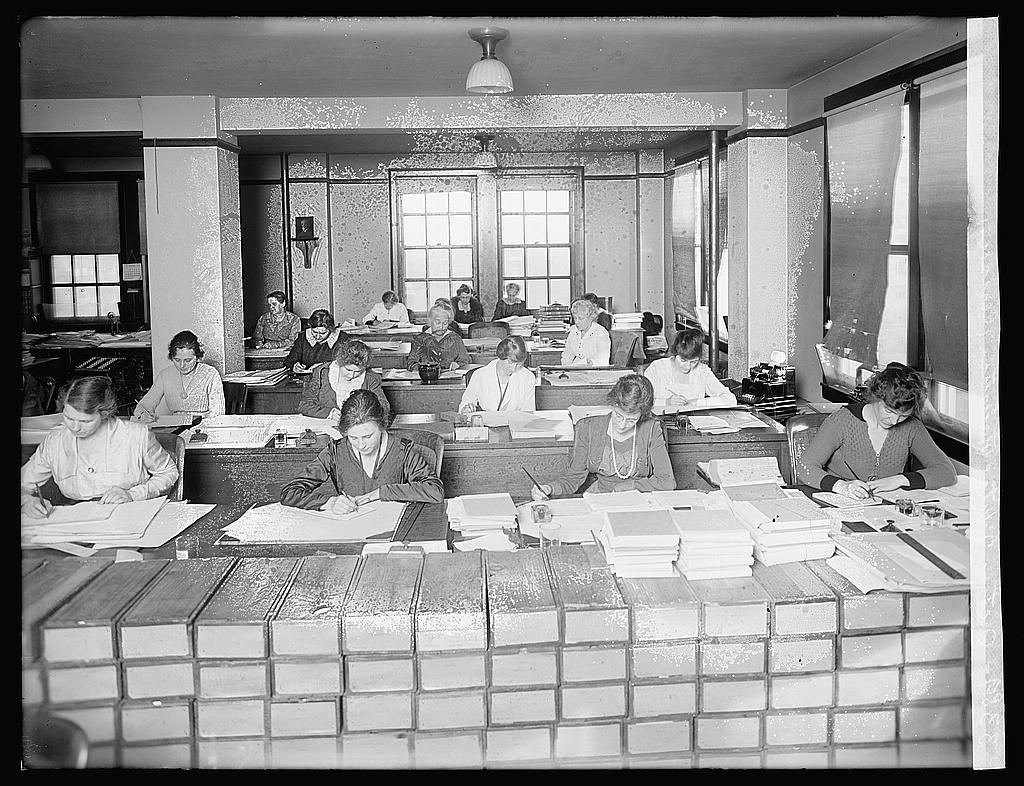

Image: “A very small section of the Census Bureau, Washington, D.C. – division of vital statistics” Between 1910 and 1930. Library of Congress.

Western Pennsylvania German census and court records offer frustration and humor. Looking for my father’s family (Scottish and English) in a county courthouse, I noticed an odd surname: “Councilman.” I pondered it for a while and realized it was an Anglicized interpretation of “Kunzelman.” The Scots-Irish court recorders’ native accent pronounced the “ou” spelling in words like “county” as “coonty,” thus leading to the odd spelling of Kunzelman. When the Pennsylvania Germans met up with the Scots-Irish English speakers having a brogue, misunderstandings ensued for their descendants to clarify. Don’t even get me started on Case (Käse, Kess, Keys, etc.).

A wonderful explanation of the varying details of the censuses and how different the information might be with closer examination.

I appreciate this writing and will be looking more in-depth at each census that I attach to my tree, I will also go back and revisit some entries where I am sure that I just quickly entered “facts” without analyzing. Thank you for such a well-written piece.

Children listed were not always birth children, as could have been grandchildren, nieces or nephews if a birth parent died or went off to work. Remarriages may show a surname change that was never an official adoption. Sometimes a friend took in a child as an extra hand…

Census records are indeed hard to read simply due to hand writting errors as well as mispelling of non-english language speakers. My family came from Spain to what is now New Mexico. at the time of the first census, people that spoke English could not communicate with the Spanish speakers of the New Mexico territory. Many records I have found have gaps, huge mispellings or completely wrong or missing names as the translators could not understand.

Census records, like all human generated records, contain errors of fact. In 1920, my mother’s brother Kenneth is properly listed as a 4 year-old boy. He does not appear in the 1930 census. In his place is a 14 year-old girl named Clara. He returned to the family in 1940 as a 24 year-old man. Neither he nor my grandparents ever mentioned his being away from the family home for any reason prior to his entering the army and his later marriage.

One more comment on census takers, particularly those in the 19th century. For the most part they would have been American English speakers unaccustomed to accents attributable to foreign languages or to English dialects of other countries. That could easily lead to odd entries. As an example, my g-grandmother Maggie (Margaret) arrived in New England from northern Ireland in 1867. On the 1870 census, I find a “Martha” living in the household of a woman I know to be her sister. It took me a few moments to puzzle out what happened. The enumerator heard her say “Margaret” but her County Down accent translated “Martha” to his ears. There were no Marthas among my Irish ancestors but the name Margaret abounded.