By Charles McGee

Conducting genealogical research from the comfort of our homes is an amazing advantage researchers have today. It grants us access to records in repositories hundreds, if not thousands, of miles away. Compared to only ten or twenty years ago it seems we’ve been liberated from the genealogical dark ages. Everything appears to be at our fingertips; just a few mouse clicks away.

But then there are the purists – those who lament the “old days” – touting the joys of digging through countless dusty books, housed in dark corners of courthouses, or searching page by page through never-ending volumes buried deep in the bowels of a local archive. Their mantra, “Only 10% of all genealogy records are online,” is pervasive in the genealogical community

Could that statistic be right?

With billions of records now online, many of them free and open to all, is there really still an absolute need for offline research?

For our genealogical research to be considered thorough, does it have to be conducted offline, in an archive, courthouse, or library?

The short answer of course is “no” – depending on what we want to know.

But here’s the catch: we don’t know what we don’t know. In other words, if we haven’t visited a repository, how can we know what we’re missing? So, the long answer, tackled in this article, is a resounding “YES!” – offline research is a must. Maybe we won’t find the missing 90% of records proclaimed by the purists, but there’s no way the trip won’t be worth it.

Where can I find offline genealogy records?

Records of genealogical interest can be found in libraries, courthouses, historical or genealogical archives, in the holdings of various churches, through local clubs, hospitals, schools, organizations and more.

You will also want to visit your local FamilySearch center. Although these centers no longer provide access to microfilm of offline records, they do allow the digital viewing of many online records that are unavailable to a general audience, and many also provide access or insights to additional local records.

One of the best ways to locate offline records is to get in touch with the genealogical or historical society local to your area of research. They can guide you to the collections you need.

You can also visit ArchiveGrid to search for special record collections in the area you plan to research. This site will provide information as to where specific collections can be found offline. Read our article about how to use ArchiveGrid here.

What records can I find offline that I can’t find online?

The vast majority of records are not yet online, and many never will be. They will either decay, be purposely or unintentionally destroyed, overlooked, or prevented from being placed online by laws that govern privacy. For this reason, you’re likely to come across all manner of records and artifacts that you will never have access to from home. The best way to illustrate this is to explain some of the things I’ve discovered over the years.

During client research at a probate records office, I came across an Application for Permit to Marry for a husband and wife related to the research. In the application, dated 20 June 1900, the couple explained they didn’t realize there was a five-day waiting period after receiving their marriage license four days earlier. Their wedding was to take place that day. Imagine the couple frantically petitioning the judge to grant them a waiver to get married so their wedding wouldn’t be ruined (which, by the way, he did)!

The 1858 marriage record of my second great-grandaunt, located at a Register of Deeds Office, was unique from any I had seen before. It was handwritten on semi-translucent, wide-lined, blue paper, seemingly torn from a larger piece (the left and right edges were jagged and somewhat brittle). A microfilm image would not have shown the color or translucency of the record, not to mention the feel of it.

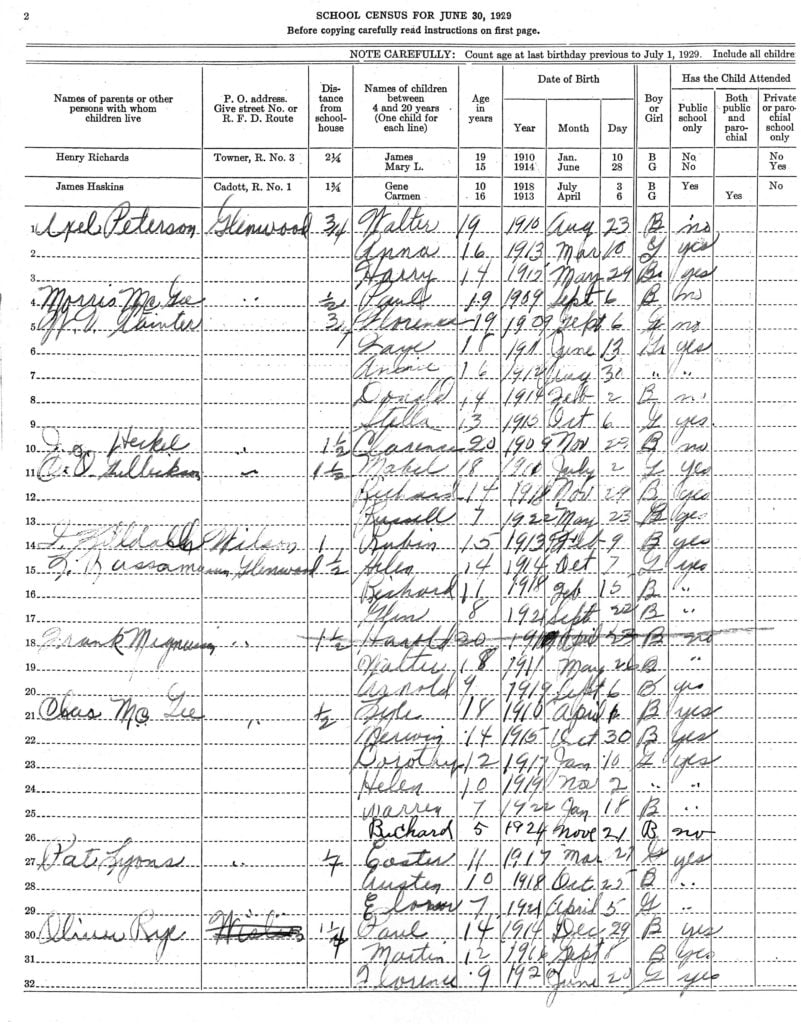

While perusing the upper shelves at another deeds office, I noticed several archival boxes titled “Clerks Annual Reports,” dating from 1908. After getting permission, I pulled one down and found it was filled with school census records for the county my grandfather and his siblings grew up in (see below). Multiple years of records showed the district they attended school in, gave their names, ages, and dates of birth, their parent’s name, and how far away they lived from school (one-half mile).

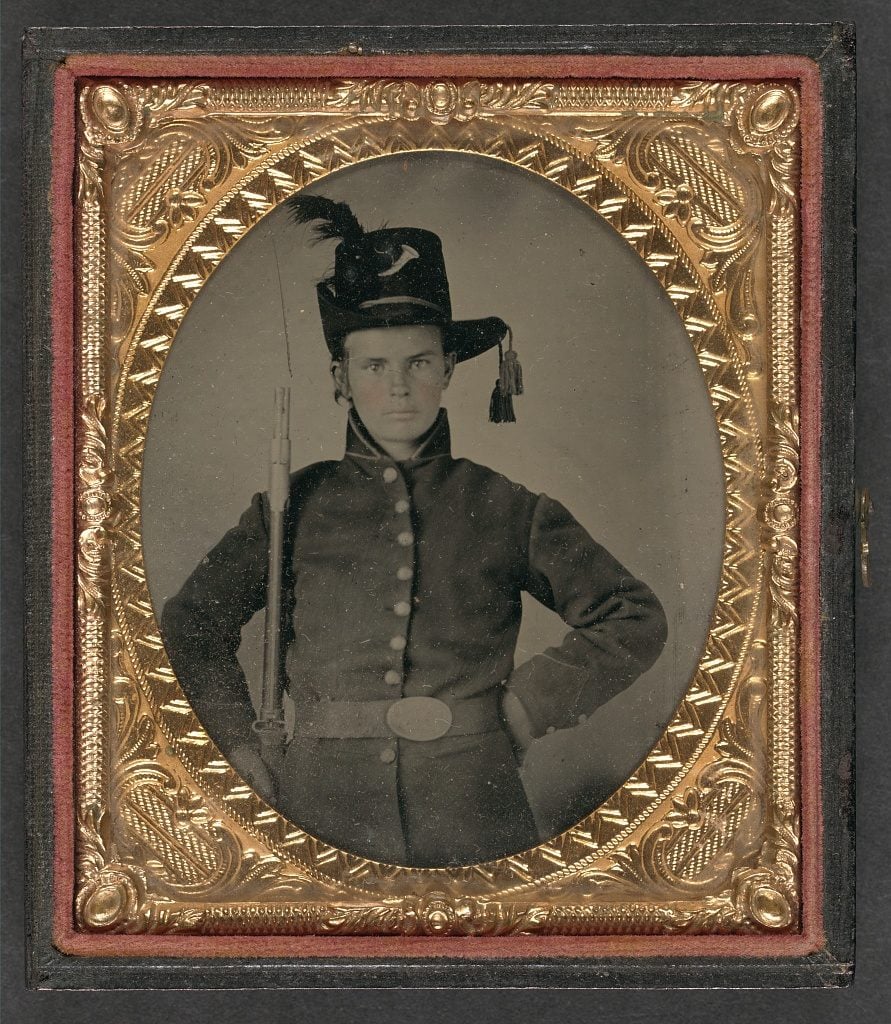

While researching for another client at a university archive, I found a Civil War tintype of his great-grandfather, very similar to the image below. The archivist required it be handled with white, cotton gloves – a first for me. In the archival box, along with the photo, was the soldier’s diary.

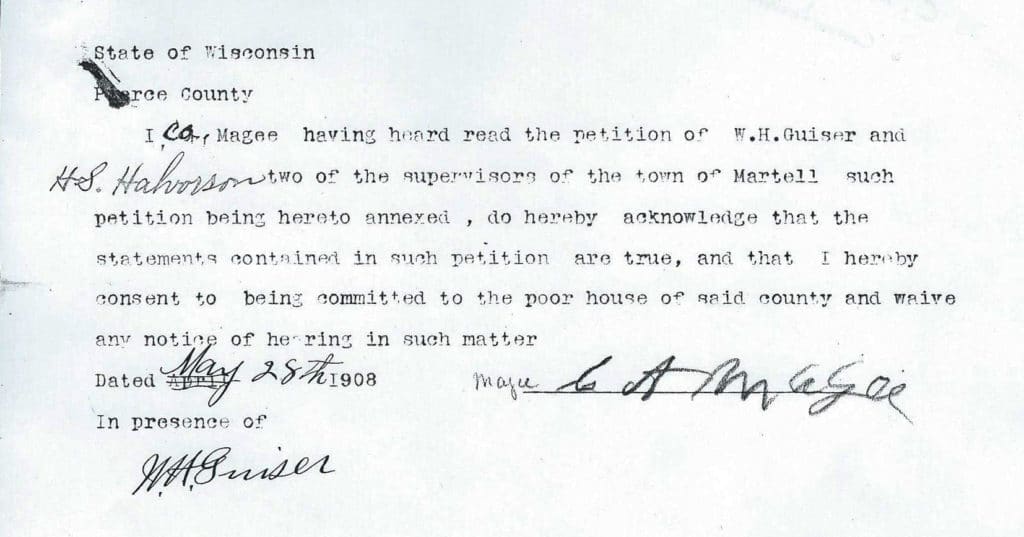

Finally, there was the case of the long-wondered demise of my second great-grandfather, rumored to have died in poverty. His story was revealed in records held at two different repositories. The first, found at the local Register in Probate Office, was an “indigent” probate record showing he was voluntarily committed to the county poor house (his signed waiver is pictured below).

Using that information, I paid a visit to the nearby university archives where I found circuit court records showing he was divorced, and county welfare records of the poor house he was committed to. While at the probate office, I noticed something else – there were three other entries for my great-grandfather in the indexes, but all were crossed out. When I asked why, the archivist explained the period for retention of those specific types of records had expired, at which time they were destroyed.

Needless to say, I was astounded and dismayed. But at least I was lucky to have acquired photocopies of his only surviving probate.

Those examples only touch the surface of what’s available. I haven’t even mentioned land records, which often have probate documents, like wills and final judgments, recorded alongside them; and manuscript collections, that could tell a long-forgotten story about an ancestor or include a family lineage.

What should you bring with you on your genealogy research trip?

Of course, this depends on the type of archive you are visiting. Governmental locations, such as vital records, deeds, and probate offices, usually have several restrictions – no computers, electronic tablets, or cell phones; no photography, pens, or food or drink, etc. – and you’ll likely have to show identification and sign in.

Repositories like genealogical societies and libraries are generally less restrictive. Regardless, I find bringing a mechanical pencil, a good-sized notebook, and a well thought out research plan does the trick.

Once you arrive, introduce yourself to the staff and explain what your intentions are. Some are more helpful than others, often giving a short tour of their holdings, but keep in mind many are places of business and often understaffed.

Treat the records you are handling with utmost care, and show courtesy and respect to the people in charge of those records. Be sure to dress appropriately too. Sweatpants might be okay for a college library (although I don’t recommend it), but not a probate office.

If you present yourself as a professional who takes their research seriously, you should get along fine. One final note: don’t show disdain for the manner in which records are filed, cataloged, indexed, or whatever. What works for one institution may not for another – space is often scarce, and funding for archives is diminishing – so just be happy you have access to the records. You never know when accessibility and retention laws will change, and what is available today may not be tomorrow.

Some important skills to remember when visiting a repository:

No matter the type of repository you decide to visit, you’ll first need certain skills and equipment. When dealing with any type of document, you should be familiar with transcribing, abstracting, and source citation. Transcribing is making an exact, word-for-word copy of the record – and an abstract is a summary of its most important details.

Illustrating these techniques is too in-depth for this article, but a quick online search for “transcribing and abstracting documents” should help get you started. (For a more in-depth study, I highly recommend Mary McCampbell Bell’s chapter “Transcripts and Abstracts,” in Professional Genealogy: A Manual for Researchers, Writers, Editors, Lecturers, and Librarians by Elizabeth Shown Mills.)

Citing the source of the record you acquired – whether you transcribed it, made an abstract, or purchased a photocopy – is one of the most important parts of your visit to the repository. At a minimum, you should record some very basic information about the document. Your source citation should be complete enough that someone else could locate the record using the information you provide. When preparing to cite a source, ask yourself the following questions:

- Where did I go to find the record?

- What kind of record is it, and how can I find it again?

- Who does the record relate to?

- When was it created? (including relevant details)

Here are a few examples of simple source citations using those questions:

A death certificate at a local repository

- [Where] St. Croix County, Register of Deeds Office, Hudson, Wisconsin.

- [What] Death certificate, volume 26, page 2.

- [Who] Elizabeth Angeline Hanvelt.

- [When] Died 30 June 1967.

A will recorded at a local repository

- [Where] Lancaster County, Register and Recorder’s Office, Williamsport, Pennsylvania.

- [What] Will, volume 1, pp. 205–6.

- [Who] Johnson Buckley.

- [When] drawn 27 April 1830, proved 12 June 1830.

A newspaper article on microfilm

- [Where] Wisconsin Historical Society Library and Archives, Madison.

- [What] Newspaper article, The Dunn County News (Menomonie, Wisconsin), microfilm P68-9.

- [Who] John Robelia obituary.

- [When] 17 August 1933, p. 3, col. 3.

These are the rudimentary details that should allow anyone to retrace your research footsteps. For a deeper study, the definitive book is Elizabeth Shown Mills, Evidence Explained: Citing History Sources from Artifacts to Cyberspace.

Vast amounts of records have been filmed and posted online, but many of the less common types may never make it to the internet. The only way to discover these hidden records is to go look for them.

If you cannot make it to an archive yourself you may be able to find a volunteer researcher (such as through Random Acts of Genealogical Kindness) to search for you, or you may be able to order a copy of a record directly from the repository itself. Check local government, historical and genealogical websites for more information. A selection of those in the U.S. can be found here.

You might also like:

How to Locate Any Offline Genealogy Record in 1 Minute

Find the Hidden Original Records for Ancestry’s Indexes With This Smart Technique

The Ultimate Quick Reference Guide to the U.S. Census for Genealogy

About the Author: Charles McGee is a professional genealogist living in Hudson, Wisconsin. He became an avid researcher in 1999, then expanded to professional work in 2011 after completing Boston University’s Certificate in Genealogical Research program. He is a member of the Association of Professional Genealogists, Secretary of the Council for the Advancement of Forensic Genealogy, and President of Wisconsin Sons of the American Revolution. Charles strives to increase and refine his knowledge and skills by studying prevailing books and journals relative to the field of genealogy, completing various educational courses, and attending genealogical institute programs, study groups, and conferences. He holds a degree in Law Enforcement, which has contributed greatly to his investigative skills. Charles can be contacted through his website at McGeeProGen.com, or via e-mail at [email protected].

Check out our immigration articles Paula, https://familyhistorydaily.com/tag/immigration/. That should get you started.

Do you have any suggestions on how or where to look for immigration information

It amazes me just how much is already out there online that can help with our genealogy research. But also that there is more to be added.

I was dismayed to read that there will also be the possibility that there will be some records that will not make their way online.

One valuable resource though that is open to us is our family, older relatives in particular. Not only can they tell us stories about our ancestors, but they may have records in their possession that can greatly help us, (particularly photographs).