The 2020 protests against racial violence and inequality are sure to be recorded as one of the most significant milestones in the history of the United States. But, as most of us recognize, it is not the first time individuals have had to band together to try and end racial injustice in America.

From the first moment Europeans stepped foot on the soil that would later become the United States, racial violence has existed and caused immeasurable suffering. Nearly every minority and immigrant group has faced some form of this injustice, but it is Black people that have been disproportionately affected.

Since 1619, when African slaves were first brought to the Virginia Colony, violence against Black individuals has been an ingrained and incredibly disturbing part of our culture. And, since that time, countless massacres and mob violence spurred by this hate, and uprisings in an attempt to end it, have taken place. In fact, BlackPast.org lists and describes more than 50 racially-driven violent events from 1712 to 1946, as well as nearly 50 more that happened after 1950.

Whether they took place in one single town, as did the New York Uprising of 1712, or in multiple locations across the country, these incidents touched the lives of many. For family historians, and Black people especially, our ancestors’ roles in those events are particularly important.

In the following guide, we’ve gathered some important tips and resources to help you find your family members in the genealogical and historical records that are available. Even if you do not discover that you have a family member that was directly impacted by racial violence, the stories of these incidents are incredibly important to read about, remember and pass on.

This guide focuses on mass racial violence against Black people. If you are interested in researching racial violence and injustice against other groups you may want to start with our genealogy guides on Native Americans, Mexican Americans and Chinese Americans – or look for more resources online.

If you are interested in researching racial violence against an individual, we suggest reading our Guide to African American Family History which provides specific help for locating records about African Americans and Black people of non-African descent.

Newspaper research can also be a good place to start for this type of research but, as we explain later, many newspapers incorrectly reported incidents of race-related violence in an attempt to protect the aggressor.

An important note about use of the word riot:

The word riot has been used, historically, to refer to many different kinds of race-related incidents – from events that would be better described as massacres or mob violence by hate groups, to others that should have been classified as protests, uprisings or rebellions by those who sought to end such injustice.

Use of the word “riot,” instead of other terms, has sometimes been called out as an attempt to paint those who stand up against oppression as violent trouble makers and can, therefore, be an act of racism itself. Other times, it is an appropriate term for aggressive uprisings most often instigated by oppressive groups against innocent people.

Because of this, we have chosen to use the word “riot” very sparingly, except where it is part of an accepted name for a historic event.

Discovering the History and Records of Mass Racial Violence and Uprisings in America

An act of racial violence against even one person is significant and appalling and deserves to be researched and remembered. This guide, however, focuses on those incidents that affected larger groups of individuals – usually, a public altercation among people of different races that involved many individuals within a community. Often these incidents begin between two individuals, or even a small group, and escalated to involve dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of people.

To Find Out if Your Ancestors May Have Been Impacted by Mass Racial Violence, Start by Choosing a Location and Time Period Your Ancestor Lived In

Many instances of mass racial violence are memorialized based on their location and the year they occurred. Placing our ancestors in a particular location at a specific time is a fundamental principle for genealogists and understanding the context of that time and place takes family history research to the next level.

For example, if you know your ancestors lived in Carroll County, Mississippi in the late 1880s, there’s little doubt they knew, witnessed, or perhaps were even involved in the 1886 Carroll County Courthouse Massacre. You can only imagine what your great-great-greats were feeling and experiencing at the time.

The best available list of large incidents of racial violence by time and place is on BlackPast.org. We encourage you to start your journey there when looking for specific history and records that may pertain to your family.

Here are some examples:

- 1863 New York City Draft Riots: Anti-Black violence that started when disenfranchised and poor New Yorkers couldn’t escape the Civil War draft.

- 1829 and 1836 Cincinnati Race Riots: The 1836 riots were a continuation of the 1829 violence rooted in the competition for jobs among Blacks and whites.

- 1886 Carroll County (Mississippi) Courthouse Massacre: Began outside the county courthouse where the trial of a white man being charged by two Black brothers for attempted murder was about to begin.

- 1921 Tulsa (Oklahoma) Greenwood Neighborhood Massacre: A false allegation that a Black man had raped a white woman to the formation of an angry lynch mob of more than 2,000 whites. Black people were run out of their homes and their businesses were looted and set on fire, and it’s believed up to 300 Black people were killed.

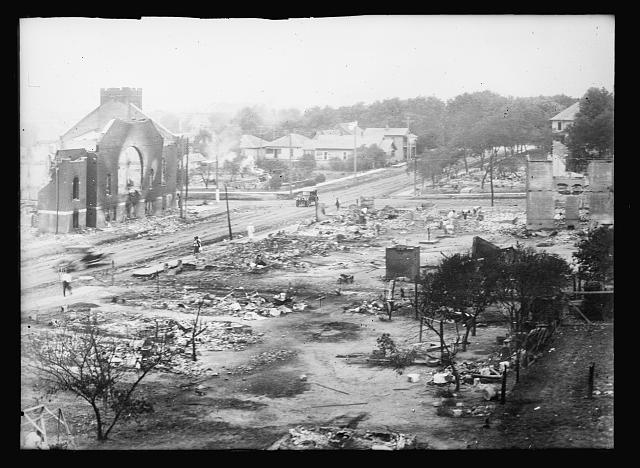

Aftermath of Tulsa Massacre, 1921. Library of Congress

Understanding Periods of Unrest

Most of today’s family genealogists will be familiar — at least from a historical perspective — with the racial unrest of the 1960s. The work of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and others in the fight for civil rights is still very fresh in our minds, even for those who weren’t alive at the time. However, many other periods of racial violence, and uprisings against it, have faded from memory or weren’t thoroughly captured in our high school history books.

Post Civil War unrest

The January 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, issued in the third year of the five-year Civil War, didn’t immediately end slavery nationwide, but it did kick-start a new era in race relations. As newly-freed slaves and former slave owners struggled to adapt to their new relationships, many people took the opportunity to incite violence.

- 1863 Detroit Race Riot: Racial tensions boiled over in Detroit during the trial of a “Spanish-Indian”/Black man accused of molesting two girls, one of whom was white. The ensuing mob left 200 Black residents homeless and fleeing the city.

- 1866 New Orleans Massacre: During the Louisiana Constitutional Convention, 130 Black residents were confronted by a large group of ex-Confederates and white supremacists — a mob organized by the mayor. Although the mayor claimed to have organized the mob to “put down any unrest,” most believe his actions were meant to prevent the Black delegates from meeting. Nearly 240 people were killed, including 200 Black Union Civil War veterans.

- 1868 Pulaski (Tennessee) Race Riot: A conflict between a white man and a Black man over a business transaction escalated into a gunfight and mob brawl, killing one and injuring four others. Two years later investigators determined the white mob participants were members of the Ku Klux Klan, which was formed in Pulaski in 1866.

Including these three events, BlackPast has documented 18 white-vs.-Black riots and massacres during the Civil War, Reconstruction, and Post-Reconstruction era from 1863 to 1899.

1919 Red Summer Riots

In 1919, people were feeling the uncertainty of a post-World War I economy and anxiety over an unstable Soviet Union. Plus, as Black soldiers returned as war heroes and more Blacks established political and economic power, many white people felt threatened and funneled their emotions into racial violence. The violence, concentrated in the months of May through September, was so widespread and consistent that the period became known as “Red Summer.”

Author Cameron McWhirter, who wrote the book Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America, cites at least 25 major mob actions that killed hundreds and injured thousands. McWhirter marks the beginning of the period as the burning of a Black sharecroppers’ church in rural Georgia in April 1919. The carnage continued in cities across the country:

- May 1919, Charleston

- July 1919, Chicago

- July 1919, Washington, D.C.

- August 1919, Knoxville

- September 1919, Elaine, Arkansas

- September 1919, Omaha, Nebraska

According to McWhirter, the various governments finally took action in the fall of 1919 when they realized “a massive riot isn’t good for business.” Instead of looking the other way when violence erupted, they jumped into action to quash it before it grew.

Potential Research Roadblocks

Once you’ve identified an event or period of racial unrest that may have involved your ancestors, you’ll probably want to learn if they were directly impacted. Unfortunately, finding the names of particular people who were involved in these violent episodes isn’t always a simple process.

Buried evidence

Often, shame and embarrassment over what had occurred, as well as the fear of a public relations nightmare, led locals to hide evidence of violence that occurred in their towns. That’s what happened in Tulsa, Oklahoma following the 1921 massacre that left hundreds dead and thousands displaced. The New York Times reported in June 2020 that Tulsa officials “destroyed documentation and spent the next 50 years pretending nothing had happened.” Even lifelong residents grew up learning nothing of the incidents.

For this reason, you may have to spend extra time digging for the information you need if, in fact, it still exists.

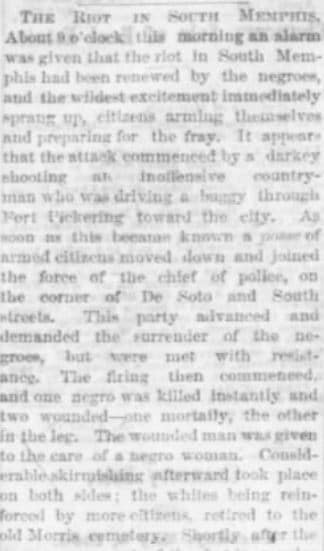

Misleading or incorrect reporting

Sometimes riots and massacres were misreported (often deliberately) by the media or written in a way that downplayed the suffering of Black victims and attempted to justify the actions of whites. For example, after two full days of violence in Memphis, the May 3, 1866 edition of the city’s Daily Appeal newspaper published a paragraph detailing only an “attack commenced by a darkey shooting an inoffensive countryman.” The story was buried in the middle of the third page of the four-page edition.

When the violence ceased on the evening of May 3, 46 Blacks and two whites had been killed. However, the only mention of the carnage in the May 4 edition of the Daily Appeal was an admonition by the paper’s editor that the city was surely exposed to “all kinds of descriptions of lawless persons from abroad.”

As with any historic research, consider the source before deciding how much of the information should be taken as fact.

Lack of recordkeeping

Another problem researchers might encounter is simply an absence of records of any kind. Although it’s believed that as more than 200 people were killed in the Elaine, Arkansas sharecropper massacre of 1919, the exact numbers are unclear. According to McWhirter, the death toll may never be determined. He told TIME in 2019. “They just went off into fields and started shooting people.”

Record Sources for Racial Violence and Uprisings

Despite these potential setbacks, there is still hope. While popular genealogy databases like Ancestry don’t carry many specific records of these incidents, we’ve identified a few promising sources for finding out if your family members were victims of racial violence or participated in important uprisings.

Newspapers

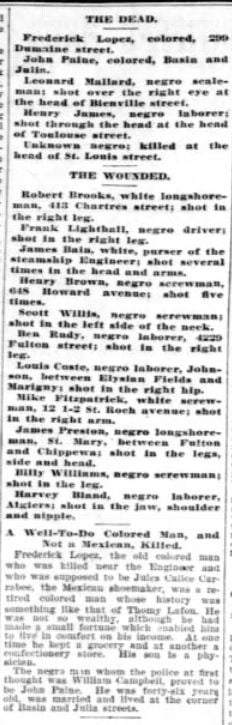

Even though some newspapers were less than forthcoming in their reporting on race riots in their towns, others were quite informative. Following the 1895 New Orleans Dockworkers Riot, in which six Black dockworkers died, the city’s Times-Democrat newspaper published two full pages of minute-by-minute details, complete with hand-drawn illustrations and a list of the dead and wounded.

The account is a boon for researchers, who might not only discover their ancestor’s participation in the event, but their occupation, home address, the geographical location of their death or injury and exactly where a bullet entered their body.

Just remember, newspapers were a product of the community they were created in, and the owner and Editor responsible for them. Use caution.

Oral stories

Some families passed down their ancestors’ stories of historical race riots through oral tradition. In 2008, the Sangamon County, Illinois State Journal Register newspaper interviewed descendants of people who were involved in the Springfield, Illinois Race Riots of 1908. The county’s Genealogy Trails website contains transcriptions of these interviews, including stories about a Black barber who was lynched by a white mob and whose shop was burned to the ground. You may be able to discover that more of these stories exist in the communities you are researching.

Anniversary commemorations

Survivors and witnesses of historical riots and massacres may have maintained their silence for decades, but revived interest in these events is helping to unearth it all, even 100 years later. In 2019, the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project (CRR19) used public art and other resources to educate people about the “city’s worst incident of racial violence.” The CRR19 website is a great repository for information and included links to interactive maps, historical documents, images, and other primary source material.

The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission is planning a similar commemoration next year. In addition to highlighting the accomplishments of Tulsa’s Black community in the early 20th century, the commission is taking a deeper dive into the details of the massacre. There also exhibits at the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum and the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Official investigations and reports

In some cases, governments and/or military units made an effort to investigate or at least record their accounts of racial violence. These reports can contain great information for family historians, including testimony of witnesses, first-hand accounts of participants, and biographical details of all involved.

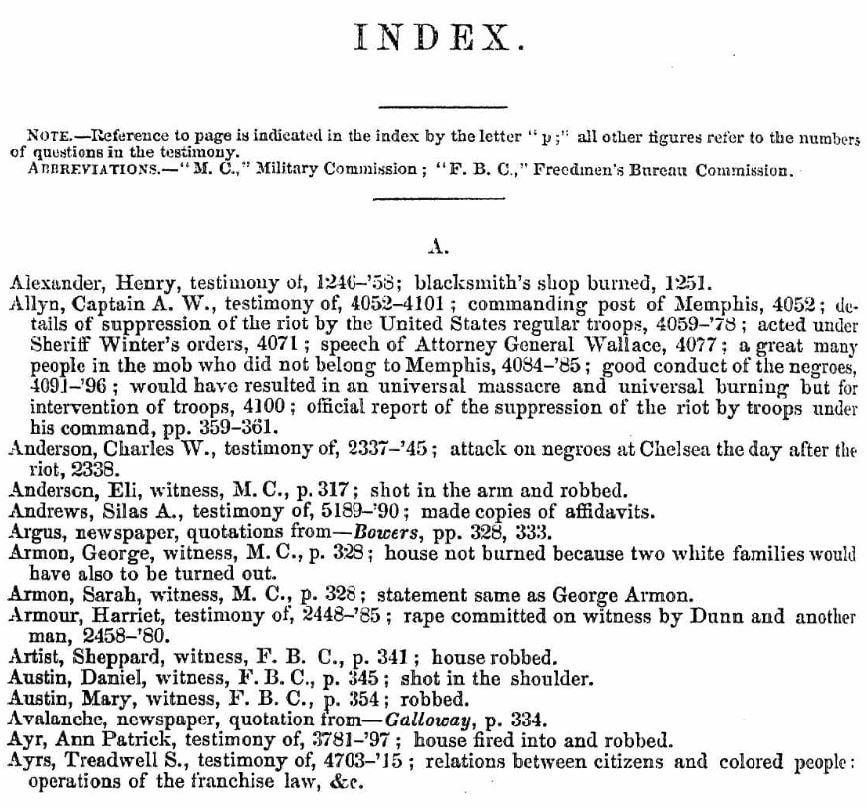

Following the Memphis riots in May 1866, the United States House of Representatives appointed a Select Committee on the Memphis Riots to “inquire into the origin, progress, and termination of the riotous proceedings; the names of parties engaged in it; the acts of atrocity perpetrated; the number killed and wounded, and the amount and character of the property destroyed.”

Portions of their report were published in The New York Times in July 1866. The full 395-page text is available in Ancestry as well (go to the Card Catalog and search for the title “Memphis Riots and Massacres.”). The index to this report contains hundreds of names — some of which also could be in your own family tree!

Another resource available in Ancestry is the Report of the “Draft Riot” in Boston. This is a first-hand recording of the 1863 riot that killed an estimated 663 people (although only 120 deaths were reported to the police). The 11-page account, from the diary of Army Major Stephen Cabot of the 1st Battalion Massachusetts Volunteers, only includes names of other military personnel and no details on the victims. However, it does help to understand the context of the riot.

Investigation into the 1921 massacre in Tulsa wasn’t commissioned until 1997 (it is said to have been prompted by the Oklahoma City bombings) and wasn’t completed until 2001. The 200-page Report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 outlines the committee’s efforts to dig up information about the riots — methods that family historians can replicate in their own research.

For example, the committee found records of 150 civil lawsuits filed after the riot, death certificates of those who died around the time of the riots, reports kept by social services, and transcriptions of interviews conducted after the fact. The report’s footnotes list hundreds of original sources for the report, which genealogists could use in their own research.

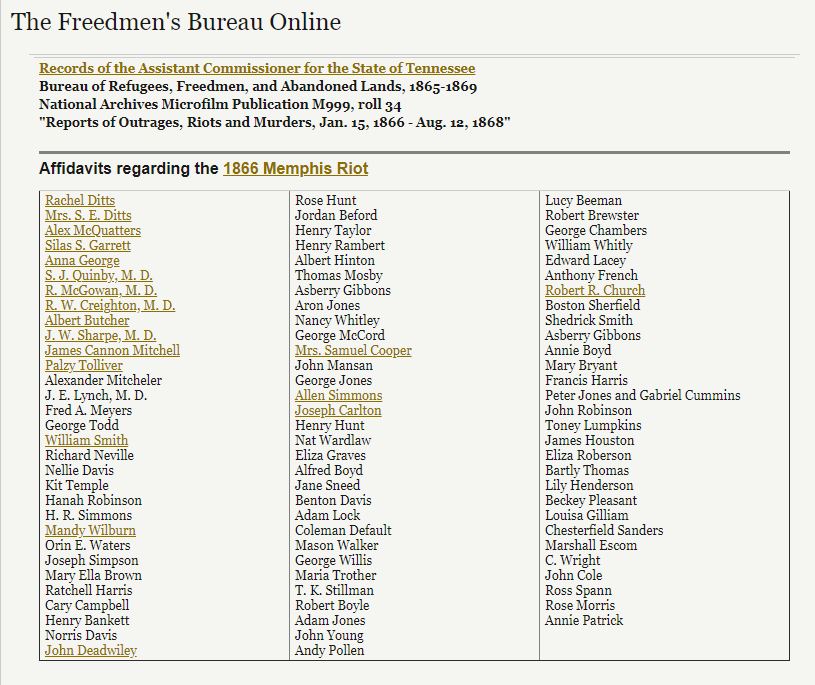

Freedmen’s Bureau Online

The Freedmen’s Bureau was established by the War Department in 1865 to supervise “all relief and educational activities relating to refugees and freedmen” following emancipation. In addition to excellent records detailing the bureau’s efforts and beneficiaries, the Freedmen’s Bureau website offers “Freedmen’s Bureau Records Relating to Murders and Outrages.”

The site explains that the term “outrages” technically means any criminal offense, it “usually referred to violent crimes by or against freedmen.” The bureau collected reports of these outrages, murders, and and other violent incidences from eight Southern states and Washington, D.C. from 1865 to 1868. Although most accounts are those of violence against individuals or small groups of Black individuals, the collection contains affidavits and reports on at least two race riots (Memphis in 1866 and Pulaski in 1868).

Other resources

Sometimes the best sources for genealogical information aren’t online. If you’ve determined, or even have an inkling, that your ancestor may have been involved in or impacted by a race riot or massacre, it might be worth your while to visit the location of the event in person (once it is safe to do so after the pandemic has eased). Historical societies, archives, and local libraries might contain hidden gems like family files, newspaper microfilm, or locally-authored books about the area’s history.

If it turns out your ancestor was a victim of racial violence, honoring and detailing their sacrifice will be your gift to future generations. And, if you find that your family member took part in violence against others, make it your job to educate yourself and others about these wrongs in the hopes that they will never happen again.

Image: Illinois National Guard soldiers questioning a man during the Chicago Race Riots of 1919. Source

By Patricia Hartley, genealogist and writer, and Melanie Mayo, Editor, Family History Daily

Also Read: