Some time ago a friend who had been adopted as an infant asked for my help in finding their birth parents. After a good bit of sleuthing, I identified and politely messaged a person who, according to DNA results, was most likely a very close relative.

Expecting an enthusiastic response and a request for my friend’s contact information, I was saddened to receive a message from this individual asking that I not contact them nor let my friend know of their existence. As it turned out, this person had also been adopted at birth. Like my friend, they had enjoyed a happy childhood with loving parents, but were not at all curious about their biological family.

Of course, I respected their wishes. As a human being, I was happy that both this person and my friend had great parents and wonderful upbringings. As a genealogist, though, I was disappointed that I wasn’t able to reunite a biological family. After all, that’s what family historians do: We often work to reconstruct our ancestral families into units of two biological parents and their children, over and over — and over — again.

Finding the Biological Parents and Other Family Members of an Adopted Ancestor in Your Family Tree

When we learn or suspect that an ancestor was adopted, it’s in our nature to pursue the identities of their biological parents. This can be particularly difficult when an adoption occurred prior to the mid-twentieth century, when laws and records were sparse and varied widely across the country. Fortunately, there are a few tactics that might help you in your search to find your ancestor’s blood relatives prior to 1950.

A brief history of adoption in the United States

Today, about two percent of the United States population is adopted, and at any given time another 100,000 children are waiting for their own “Gotcha Day.” Although families have been taking non-biologically related children into their homes for all of history, adoption laws in the US only came into being in 1851 when Massachusetts passed the Adoption of Children Act.

Massachusetts’ historic act was the first law to recognize adoption as a “social and legal process” and ensure that adoptees were placed in “fit and proper” arrangements. In other words, it was the first law to protect the interests of adopted children rather than the adults who were involved.

This approach continued throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, as organizations were formed with the explicit purpose of finding suitable permanent homes for children rather than placing them in orphanages for the long-term. The first adoption agencies appeared in the early 1900s, working on behalf of married couples seeking to adopt.

Prior to 1851, though, adoptions were largely informal arrangements, with few cases being managed through a legal process. In many cases, relatives or neighbors took orphaned children, or those who couldn’t be cared for by their parents, into their homes. Whether out of responsibly, need or love, these arrangements often became permanent.

If no one volunteered to assume care, children became wards of the local government, and were often bound through apprenticeship or indenture agreements with families who needed extra labor for farms, households, or businesses.

Clues to historic adoptions in family trees

With very few formal or legal procedures to record adoptions, it can be difficult to uncover such a relationship among ancestors in your tree prior to the early 1900s, by which time most states had followed Massachusetts’ lead and enacted their own adoption laws.

However, you may stumble across some clues in your family history research that point to a historic adoption situation.

Here are some clues that may reveal an adoption in a family tree:

- Family lore — While some families chose (and still choose) to keep adoptions private, even from the adoptee, stories of children being adopted or given up for adoption may have filtered down through the generations.

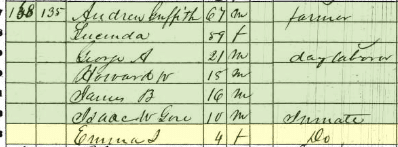

- Census annotations — You might find a person listed as “AD daughter” or “adopted” in the relationship to head of household column. Additionally, a child may be listed as “inmate” within the household, as Isaac W. Gore and Emma I. Gore were annotated in the household of Andrew Griffith in the 1860 U.S. Federal Census of Greenup County, Kentucky:

- Different last names — If a child appears in a census or other record as living in a household with a different name, they could be an illegitimate child, a child from a wife’s previous marriage, or an adoptee. You should explore all of these avenues.

- Notations in probate records or wills — Adopted children were often listed as such in a last will and testament (“my adopted son”) or a legal record of heirs.

- Guardianship or apprenticeship records — Although these documents aren’t equivalent to adoption documents, an appointment of a guardian over minor children or an apprenticeship agreement could indicate such a relationship.

Sometimes these clues themselves might offer leads to the names of a child’s potential birth parents or provide direction as to where to look. For example, the names of suspected parents of an adoptee may be passed down through family stories or an adopted child may be listed in a will as “the child of my late sister Sarah.”

Likewise, if a 12-year-old child suddenly shows up with a family in the 1860 census, you can look for a 2-year-old child with the same name in the 1850 records, hopefully living with a birth parent. The most likely suspects to investigate as birth parents will be deceased family members or neighbors. Once you’ve exhausted those avenues, though, it’s time to expand your search.

Pre-1950s record collections to review when looking for records of adoption

Adoptions occurring prior to the early- to mid-1900s definitely present challenges to a family historian. There is some good news, however. Prior to 1917, adoption records were not sealed and weren’t considered confidential. In fact, most states didn’t push for sealed adoption records until the 1940s. This means that if records of your ancestor’s adoption exist, you should be able to access them — if you can find them, that is.

Here are a few places to start looking for adoption records:

Original birth certificates

Most states began keeping birth records and issuing birth certificates by the first decades of the twentieth century. If a child was adopted, the state issued an amended birth certificate listing the adopted parents as the child’s parents. This certificate became the document of record, and in most states, the original birth record was inaccessible, sometimes even by the adoptee.

Today, each state still maintains its own laws as to who can access an original birth certificate and what is required to gain access. Each state’s access requirements are available from the Child Welfare Information Gateway.

Orphan train records

As attention shifted in the 1850s from the needs of adults to the welfare of orphaned or abandoned children, various orphanages and groups partnered with the newly-founded Children’s Aid Society to relocate the children to suitable homes across the United States and Canada. From 1854 to 1929, the society transported an estimated 250,000 children to their new families via the railroad system, eventually becoming known as “orphan trains.”

The majority of orphan train riders were from New York, and farming families in the Midwest took in the most children. However, riders originated from many other areas and ended up in 45 American states, as well as in Canada.

According to the National Orphan Train Complex (NOTC) Museum and Research Center in Kansas, there was no centralized record-keeping system of riders. Each organization that placed children on the train kept its own records, though. If you suspect your ancestor may have been a rider, you might check out these resources:

- Orphans Placed in the New York Foundling Hospital and Children’s Aid Society 1855 – 1925 — This Ancestry.com database contains names and information of about 18,000 orphan train riders.

- New York Historical Society — Many of the archived records from organizations placing orphan train riders are housed here, but many are restricted. For more information, email [email protected]. (There is a fee for contracted research).

- National Orphan Train Complex and Orphan Train Heritage Society of America — The NOTC website offers several first-person accounts from riders and contact information for numerous archives that might contain orphan records. Fees for research may apply.

County court records

Adoptions were sometimes recorded by county probate courts. In fact, many early probate court records are listed under “orphans’ courts” as the probate process originated from the need to protect orphaned children and their rights to a deceased family member’s estate.

Two states (Maryland and Pennsylvania) still refer to their probate courts as orphans’ courts, although the responsibilities have expanded far beyond protecting orphaned children.

Once you’ve identified the birthplace of an adopted ancestor, search for his or her name and the names of the adopted parents in the county’s probate records, many of which are available online. Some collections are labeled as adoption records, such as these that are freely searchable on FamilySearch:

- Coahoma County, Mississippi Index to Adoptions

- Wood County, Ohio Adoption Final Record

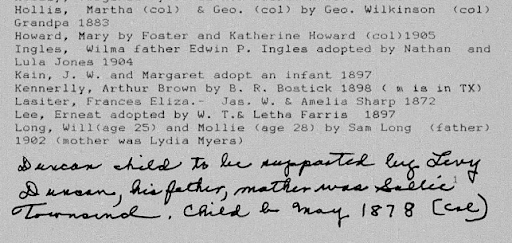

- Franklin County, Tennessee Adoptions and Apprenticed Children (see excerpt from this collection below)

Catholic church records

In the Catholic church, the sacrament of baptism is administered soon after a child’s birth. If an adoption occurred later, the original baptismal documents may contain information about the child’s birth parents. Some Catholic baptism records are available online, but you could also consider contacting the Catholic churches in the area where your adopted ancestor was born to ask where you might find records from the appropriate timeframe.

Orphanage records

Records and sources of additional information about several orphanages have been published on FamilySearch, Ancestry and other databases. To discover what’s available, go to the database’s catalog and search for the keyword “orphanage.”

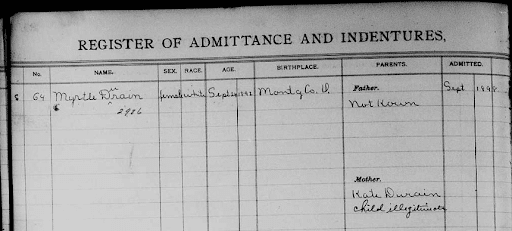

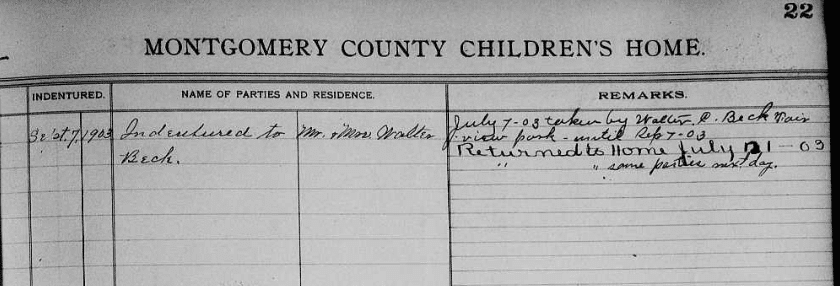

Results are sorted by geography, so you can easily narrow down your results. The images below from the Montgomery County (Ohio) Children’s Home records on FamilySearch reveal a wealth of information about young Myrtle Durain, including her birth mother’s name, her status as “illegitimate,” and the names of the family to whom she was indentured.

Adoption or children’s aid agencies or maternity homes

Depending on the timeframe and the laws of the state in which an adoption occurred, you may be able to request records of an adoption directly from the agency that handled a child’s placement. Research which adoption agencies or women’s maternity homes were in existence at the time of the birth through search engines, city directories, and newspapers, or contact the local historical society for assistance. It’s possible that these records were transferred to a local archive when these organizations shut their doors.

Using DNA data to uncover adoptive parents

While documentation is always the gold standard when it comes to genealogical research, there’s nothing more concrete than a close DNA match to prove a familial relationship to another person (remember that matches become less reliable beyond the fourth cousin range).

The Internet is full of stories of adopted children who were reunited with their birth parents and vice versa after submitting a commercial DNA kit. While a parent/child relationship is obvious when it’s the child or parent submitting their sample, determining the parentage of an ancestor several generations back can be a little more complicated.

Tools like MyHeritage’s Theory of Family Relativity and Ancestry’s ThruLines can help narrow down potential parents, but these suppositions should be thoroughly explored and backed up with documentation.

Should you reach out when you discover an adoption through genetic research?

Remember my story about contacting a member of my friend’s birth family? Even though we as family historians hope that a person we’ve identified as being related to an adoptee will be thrilled that we’ve found them, we have to understand that not everyone wants to learn about an adoption in their family — even if it occurred generations ago. Adoption and all of the events that lead to it and follow it are extremely emotional, and should be handled sensitively (here are some suggested messages to use when contacting a DNA match).

Above all, don’t be discouraged or hurt if the person you contact regarding a historical adoption doesn’t respond, or responds with anger. Instead, be polite, respect their wishes, and continue to gather research from other sources — like the ones we’ve listed above. Remember, too, that a blood relationship isn’t the only thing that makes a group of individuals a family! Read this interesting article about what constitutes family in a family tree.

By Patricia Hartley, lifelong genealogist and regular contributor to Family History Daily.

I’ve been working my GGUncle’s wife who, from a note from a relative, was born in Joliet, IL in 1865 as Emma V. Hurelle and her Hurelle grandparents were from France. Her father was a sheriff who was killed in Chicago. With this Illinois connection, I wondered if she was a part of the Orphan Trains. I believe I found her in the 1870 Census Randolph, IL, age 5, living with Fredrich Benjimin who was born in Prussia. In the 1880 Census Fly Creek, NY, she was age 15 and “a” adopted by Rhodolphus and Maryette Ferns Benjamin (not sure if he was related to Fredrich). In 1893, she married my GGUncle Walter House in Otsego County. Dr. William L. Hurelle and Jane Van Court Hurelle, who were also living in Otsego, NY, were they possible relatives of Emma? Could her middle initial be Van Court? The 1880 Census says William L. Hurelle’s parents were born in France. There is an Alexander Hurelle born Oct. 26, 1831, died June 23, 1868, buried in Cooperstown, Otsego, NY. Is he Emma’s father? His date of death, 1868, makes sense. Or William L. Hurelle’s brother? Alexander was born 1831 and William L. was born 1832. I love trying to figure these things out. Research is ongoing.

My Boyfriend found out right after his mom passed , that she had been adopted. I am trying to figure out how to go about who her parents were. He did take a DNA test through Ancestery.com ..I am not sure about her birth certificate , we have the one through her adopted parents. Her adopted father was a Dr. in Buffalo NY so it was a very private adoption. So not sure if the original even exists . I just sent for your free check list I sure hope I can figure this out. I also know that my bf put up a son for adoption when he was 19 or 20.

Hi All! We too adopted 2 children who decided to have their DNA taken which of course did eventually identify who their birth or bio parents were – that is except our son’s birth father’s families…

This is very important since we are working to find them because he has 2 brain tumours and the Neuro researchers hope to add his case worldwide research. We used our skills as Genealogists with much too-ing and fro-ing among the varying types of records available to us. Sadly his Bio mother placed 5x 10years of Vetoes against him discovering his BF’s identity which we still have not sourced but a 3rd cousin DNA match has told us of her Mother and 2x 1st cousins, also 1st cousins, who succumbed to Brain Tumours. mystery to us is why have your DNA taken and not use it to make family connections? We placed warnings to some of his closer DNA matches that if they had any sinister headaches or similar that they have them investigated. We could do no more. Only one response after that! Anyway we know that BF will be discovered and hope that we will find more about his families as we have grandchildren who want to know more of their heritage IT IS THEIR RIGHT AS HUMANS TO KNOW THIS INFORMATION!

18 months ago I found out through DNA testing that I was a biological father of twins from when I was a teenager. I couldn’t believe it, and am ecstatic about it. Before contacting them I prepared myself if they didn’t want to make contact or if they just wanted medical history. Fortunately they were as happy as I am. I’ve met them and now spend holidays with them and their adoptive parents. Happy introductions and lasting relationships do happen. You have to be open, expect nothing in return, then hope for the best.